Being Brahms

The surprising snippets of autobiography embedded in his music.

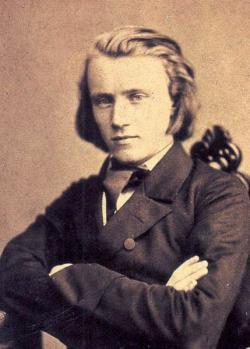

Meister Raro/Wikimedia Commons.

In 1883, Johannes Brahms made another of his summer working sojourns in country towns and spas. He generally composed in the warm months and left the rest of the year for performing and copying out the summer's production. Much influenced by landscape in his work, he may have chosen this town for its setting: Wiesbaden on the Rhine. There he found a high airy studio looking toward the river and got to work on his Third Symphony.

His First Symphony had taken over 15 years to finish, probably because of his uncertainty about how to proceed after its searing first movement, but definitely because of his anxiety over taking on this genre: "I'll never write a symphony!" he’d once groaned. "You have no idea how the likes of me feels with the tramp of a giant like him behind you!" By "him" Brahms meant Beethoven. But the First had gotten done finally, and soon after that he completed the warm and pastoral Second in a single summer. With the Third, which he finished in that summer of 1883, he wrote in many ways his most personal symphony.

Before leaving for Wiesbaden, Brahms had celebrated his 50th birthday in Vienna with two friends, surgeon Theodore Billroth and Eduard Hanslick. The latter was the most powerful music critic in Europe's capital of music. Hanslick is mainly remembered for his regular lambasting of Richard Wagner and his "Music of the Future" agenda, shared with Franz Liszt and other composers of the time who rejected the forms of Mozart, Beethoven, et al., and based much of their work on stories. Wagner wrote what he called "music dramas"; Liszt invented the orchestral "tone poem" built on literary models. The other side of the musical equation in the 19th century were those like Brahms who upheld the old "abstract" formal models and allied musical genres: sonata and rondo forms, also symphonies, string quartets, and the like.

The upholders of old forms constituted the Brahms faction in theory, but its practical and intellectual leader was Hanslick. Brahms stayed away from overt politicking. Early in his career Hanslick wrote a treatise called "Beauty in Music," in which he declared, "Definite feelings and emotions are unsusceptible of being embodied in music." This was the doctrine of "pure," aka "abstract" music. It was held up against the Wagner/Liszt school and associated with Brahms in his time and later.

What did Brahms himself think of all this? To begin with, he admired Wagner's work and said so—if only in private conversations—without being the least interested in Wagner's ideas. As for Hanslick's treatise, Brahms once told Clara Schumann he had tried to read it but, "I found such a number of stupid things in it that I gave it up." But Brahms and Hanslick needed one another; the composer needed a champion, the critic needed a bastion against Wagnerism. They became friends and let their differences lie.

To this day, Brahms is associated with the idea of abstract music, free of literary models, free of autobiography. But that's not his doing; clearly a good deal of his music came out of his life. For all his intense privacy, now and then he let something slip, usually in his oblique fashion. Once he wrote his publisher a supposedly joking suggestion that the cover of his C-Minor Piano Quartet might have a picture of himself dressed in the famous outfit of Goethe's fictional Young Werther, who killed himself for love of another man's betrothed. That quartet had first been drafted years before, in a time when the young Brahms was in a similar situation. He fell in love with Clara Schumann while her husband Robert, Brahms's discoverer and mentor, wasted away in an asylum. Later he fell for Clara Schumann's daughter Julie. When he heard Julie was getting married he wrote the despairing Alto Rhapsody, which he told Clara was his nuptial song. His friends knew that a theme in the G-Major String Sextet spelled out in notes the name of a woman he had jilted after they exchanged rings.

But Brahms was a guarded man, and most of the time he did not talk about the inspiration of a piece. In the same spirit, he destroyed most of his working sketches for pieces. He had, however, picked up from Robert Schumann the idea of symbolizing people in notes. Besides the above example in Brahms's Sextet, another is Robert's "Clara theme," which incorporates C A A, the musical letters of her name. Brahms used that theme several times, the last in one of his late Four Serious Songs that he explained, privately, "have to do with Frau Schumann." For Brahms as for both Schumanns, to use a theme evoking a person made that person part of the music. In works of both Brahms and Robert Schumann, Clara was present in her theme.

This brings us back to the Third Symphony, which opens memorably like this:

Brahms never talked about it, but that theme is Robert Schumann's, from the first movement of his Symphony No. 3. Brahms borrowed not Schumann's main theme, but rather a derivation of it that appears in the middle of the movement2. By way of his theme, Schumann is present in Brahms' Third Symphony. Why?

To answer that question we have to recall the most dramatic period in Brahms' life. In Wiesbaden, when he looked out his window to the Rhine, he had to have thought of his friend Robert Schumann, who in a famous article written when Brahms was 20 and Schumann 43, proclaimed this young man to be the future of German music. There followed Robert's suicide attempt in a fit of madness, his lockup in an asylum, and the helpless love Brahms came to feel for Robert's wife Clara, one of the great pianists of her time. When Robert finally died in the asylum, Brahms fled Clara. He was not cut out for marriage, but she remained the love of his life. Those years of Robert's mentoring, his madness, and death, and Brahms' passion for Clara, remained in Brahms' mind for the rest of his life.

Robert Schumann called his Symphony No. 3 the Rhenish. In other words, it's about the Rhine, which for German Romantics was a kind of mythical river. Wagner set his whole Ring of the Nibelung around it. It was in the Rhine that the high-Romantic Robert Schumann chose to jump in his suicide attempt. So for Brahms the river and the memory of those years were joined. Likely that association of person and place is why the river and his memories around it came out in the symphony that begins with Robert's theme, and so with Robert himself. To some degree, this is a work in which, hidden in notes, Brahms looked back over his life.

Still, Brahms was not a composer of tone poems, and as far as one can tell most of his Third Symphony is largely laid out in abstract terms. The opening Schumann idea is more a tag than a theme; it only returns in the recapitulation and the coda of a first movement that mingles anguished sections3 with lyrical ones4. That mingling of pain and lyrical joy may be a telling matter, but it is not overtly tied to the triad of Robert, Clara, and Johannes.

The main theme of the second movement is hymnlike5. Clara wrote Brahms that it reminded her of a chapel in the forest. I suspect few people forget the first time they hear the third movement, with its yearningly beautiful, sui generis theme6.

The finale begins with an ominously murmuring gesture7 and returns to the anguished tone of the first movement. Even the contrasting second theme in C major has a detectably desperate quality8. Meanwhile Brahms has not forgotten the Schumann theme, which never quite found peace and resolution in the first movement. After a towering climax, the finale sinks into a long, quiet coda9 mainly based on a chorale theme that first showed up in the second movement. It is surrounded by flutters, and the coda adds up to a sense of autumnal reflection and recollection—of earlier parts of the symphony, and of its composer's life.

At the end of the symphony we arrive back at the Schumann theme, drifting downward in a magical, murmuring atmosphere10. At the end of the theme, over and over, we hear harmonies that suggest a phrase Brahms knew well, the "Farewell" motif11 that begins Beethoven's Lebewohl (Farewell) Sonata.

There is the autobiographical essence of the Third Symphony, written on the Rhine and recalling Schumann's Rhenish Symphony. Among other things, the Third is Brahms' farewell to all that, to the most exciting and agonizing period of his life, his Young Werther years, and his tragic mentor Robert Schumann.