The Real Secret of War Photography

-

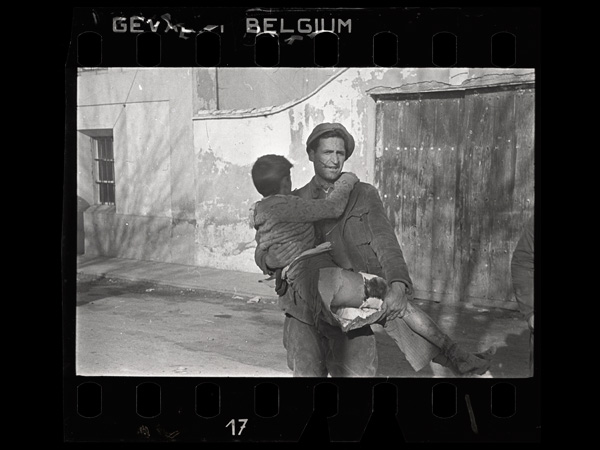

CREDIT: Robert Capa, Man carrying a wounded boy, Teruel, Spain, late December 1937. © International Center of Photography/Magnum Collection International Center of Photography.

CREDIT: Robert Capa, Man carrying a wounded boy, Teruel, Spain, late December 1937. © International Center of Photography/Magnum Collection International Center of Photography."If your picture's not good enough, you're not close enough." So said the quotable, picturesque war photographer Robert Capa. By Capa's rule, the best photographs of the Spanish Civil War (1936-39) weren't his and they weren't made by his companion, Gerda Taro, either (even though she was close enough that a friendly tank killed her). The best pictures were made by David "Chim" Seymour, their mutual friend and the master portraitist among them. He took the closest shots.

About 4,500 of the Spanish Civil War negatives of Capa, Chim, and Taro, missing for nearly 70 years, are now on display in the International Center of Photography's historic show, "The Mexican Suitcase: Rediscovered Spanish Civil War Negatives by Capa, Chim, and Taro."

-

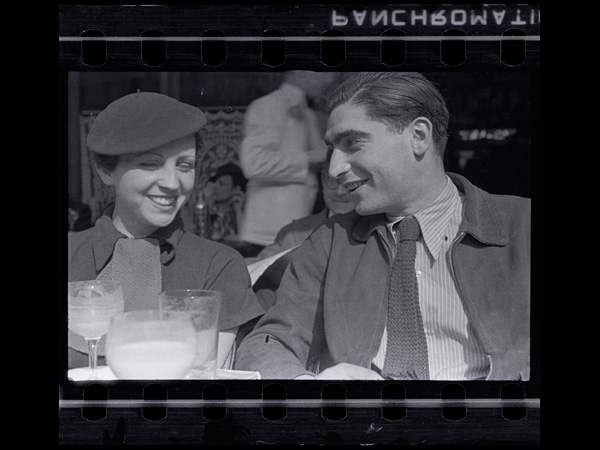

Fred Stein, CREDIT: Gerda Taro and Robert Capa on the terrace of Café du Dôme in Montparnasse, Paris, early 1936 © Estate of Fred Stein/International Center of Photography.

Fred Stein, CREDIT: Gerda Taro and Robert Capa on the terrace of Café du Dôme in Montparnasse, Paris, early 1936 © Estate of Fred Stein/International Center of Photography.Thoughtfully, the curator of "The Mexican Suitcase," Cynthia Young, has arranged the pictures chronologically, showing not only some of the iconic prints but the contact sheets they came from and the pictures as they ran in Regards, Life, Vu, Ce Soir, Madrid, and Revolution. So you can follow the war as you go. And since each photographer entered and departed the war at a different time, you can also follow their works and lives.

Looking at the three photographers' works side by side suggests a new war-photo maxim: In pictures of war, the magic ingredient isn't proximity but charisma.

Charisma, as Chim, Taro, and Capa all knew, comes in many forms. Before the war, all three cast off their Eastern European names and took on jaunty new ones. Endre Friedmann (1915-1954), a Hungarian, became Robert Capa; Gerta Pohorylle (1910-1937), a Jewish-German refugee, became Gerda Taro; and Dawid Szymin (1911-1956), a Polish Jew, became David Seymour, or just "Chim."

Two kinds of charisma—the kind that goes on behind the camera and the kind that goes on in front of it—are on display in this show. Here, in a shot by Fred Stein taken at Café du Dome in Paris before the war began, you can see what rock stars Capa and Taro were.

-

Robert Capa, CREDIT: Ernest Hemingway (third from the left), New York Times journalist Herbert Matthews (second from the left) and two Republican soldiers, Teruel, Spain, late December 1937 © International Center of Photography/Magnum Collection International Center of Photography.

Robert Capa, CREDIT: Ernest Hemingway (third from the left), New York Times journalist Herbert Matthews (second from the left) and two Republican soldiers, Teruel, Spain, late December 1937 © International Center of Photography/Magnum Collection International Center of Photography.Capa and Taro, of course, weren't the only ones whose charisma turned the Spanish Republicans' fight against the fascists into a worldwide, Bono-style cause célèbre. Shortly after the fascist general, Francisco Franco, overthrew the democratically elected Spanish government, writers and artists flocked to the Republicans' side: Ernest Hemingway, Pablo Picasso, Federico García Lorca, André Malraux, and Emma Goldman all came, along with assorted journalists. (The New York Times' Herbert Matthews, second from left, is shown here with Hemingway.)

Some celebrities fought, and some died (García Lorca was killed in Granada). Some made speeches. Some made paintings (Picasso's Guernica, for example). Some made films. Some took pictures. Some had their pictures taken.

-

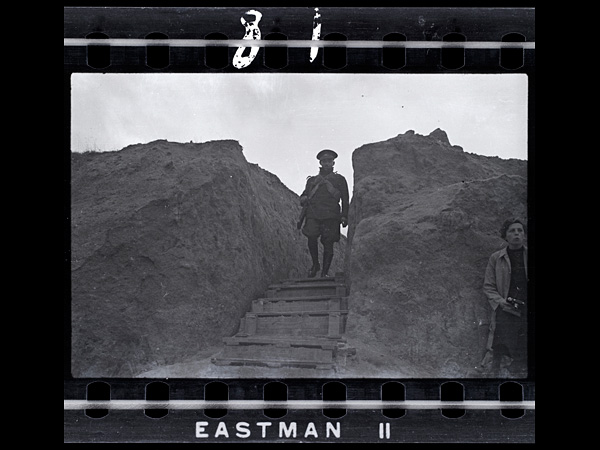

Robert Capa, CREDIT: Republican officer and Gerda Taro, University City, Madrid, February 1937 © International Center of Photography/Magnum Collection International Center of Photography.

Robert Capa, CREDIT: Republican officer and Gerda Taro, University City, Madrid, February 1937 © International Center of Photography/Magnum Collection International Center of Photography.Simultaneously the world got its first glimpse of the horrors of fascism (Hitler and Mussolini both helped Franco) and its first taste of a "media war." For artists, writers, and, yes, even journalists and photographers, being partisan was part—indeed the point—of being there. Or to put it in Capa's words: "In a war, you must hate somebody or love somebody; you must have a position or you cannot stand what goes on."

How was the love shown? Mostly through attentiveness. It's no accident that most Spanish Civil War photographs we know are of Republican soldiers, because most photographers we know of were on that side. You can see how cozy they were. Here Taro, whistling in the shadows, holds her camera, while a Republican officer comes down some makeshift stairs built into the trenches near Madrid. Just another day at the office.

-

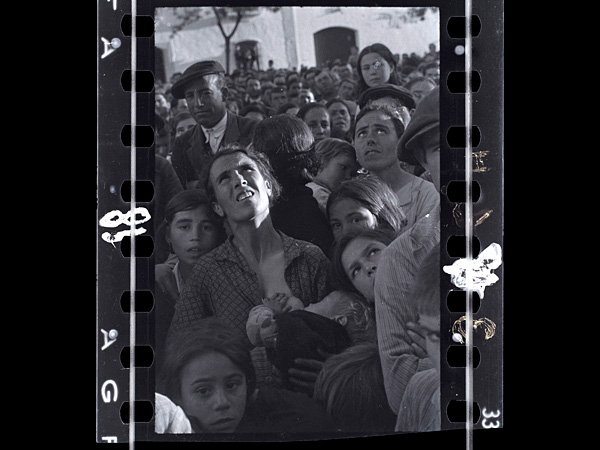

Chim (David Seymour), CREDIT: Outdoor mass for Republican soldiers, near Lekeitio, Basque region, Spain, January–February 1937 © Estate of David Seymour/Magnum International Center of Photography.

Chim (David Seymour), CREDIT: Outdoor mass for Republican soldiers, near Lekeitio, Basque region, Spain, January–February 1937 © Estate of David Seymour/Magnum International Center of Photography.The photographers weren't above making propaganda. Chim, for instance, dwelled for weeks on the religious ceremonies in the Basque region to counter Franco's denunciation of the loyalists as anti-Catholic, anti-art brutes. And Taro and Capa were known to stage maneuvers for the camera. Indeed, their reputation for doing that would later fuel suspicions that Capa had actually staged his most famous picture, "Falling Soldier," which shows a man falling backward the moment he's shot.

-

Chim (David Seymour), CREDIT: Mother nursing a baby while listening to political speech, near Badajoz, Extremadura, Spain, late April–early May 1936 © Estate of David Seymour/Magnum International Center of Photography.

Chim (David Seymour), CREDIT: Mother nursing a baby while listening to political speech, near Badajoz, Extremadura, Spain, late April–early May 1936 © Estate of David Seymour/Magnum International Center of Photography.Newsmagazines could be even more brazen. This Chim photograph of a mother gazing up at something while nursing her infant, which first appeared in the French magazine Regards, was taken during a land reform meeting in Badajoz, Estremadura, in the spring of 1936, before the war began. But when it ran on the cover of Madrid, in 1937, it was shown as part of a wartime montage, with bombs drawn in, to suggest that the nursing mother was actually watching an air raid.

-

Gerda Taro, CREDIT: Spectators at the funeral parade of Gen. Lukacs, Valencia, June 16, 1937 © International Center of Photography Collection/International Center of Photography.

Gerda Taro, CREDIT: Spectators at the funeral parade of Gen. Lukacs, Valencia, June 16, 1937 © International Center of Photography Collection/International Center of Photography.Of the three photographers in this show, Gerda Taro, who covered the war alongside Robert Capa, had the shortest run—less than a full year. In the spring of 1937, she was photographing military drills in Valencia and ruins in Madrid. By the end of the summer, she was dead at the Battle of Brunete, killed by a tank while riding on the running board of a car carrying wounded soldiers from the battlefield.

It's hardest to get a sense of her work, both because of her short career and because she filed some of her work under the heading Capa & Taro. But from the evidence in the exhibition, Taro, unlike Capa, had trouble focusing her camera, particularly during wild action. And her attempts at photographing heroics fall flat. In this shot, the fist-pumping women seem to be asking with their eyes if they're really doing it right.

-

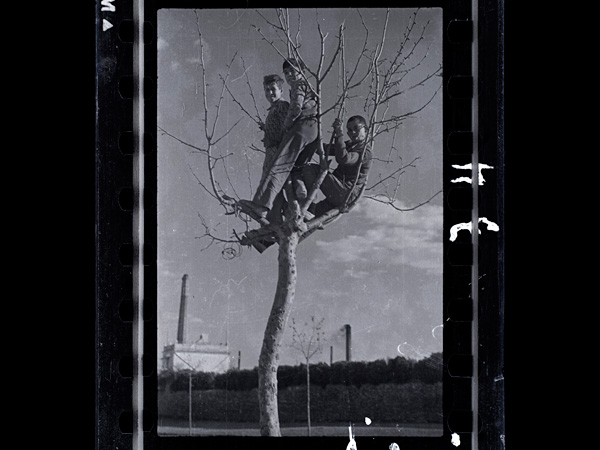

Gerda Taro, CREDIT: Children view the training of the New People's Army, Valencia, March 1937 © International Center of Photography Collection/International Center of Photography.

Gerda Taro, CREDIT: Children view the training of the New People's Army, Valencia, March 1937 © International Center of Photography Collection/International Center of Photography.Taro excelled at photographing corpses, drills, and lineups. She had a surrealist bent. And she often shot from below, holding her camera at her waist. That odd upward angle—the exact opposite of Chim's—is her most distinctive mark.

-

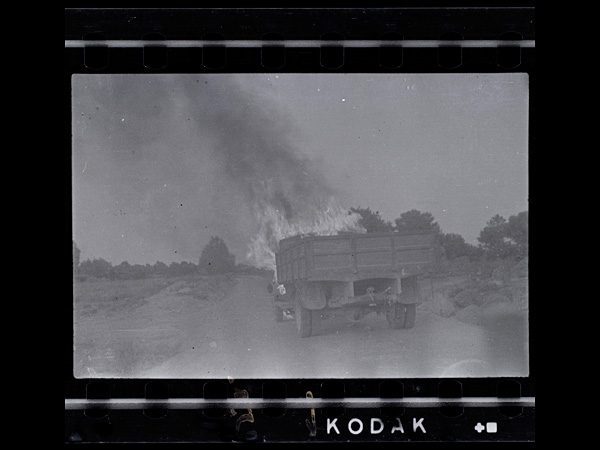

Gerda Taro, CREDIT: Truck on fire, Battle of Brunete, Spain, July 1937 © International Center of Photography Collection/International Center of Photography.

Gerda Taro, CREDIT: Truck on fire, Battle of Brunete, Spain, July 1937 © International Center of Photography Collection/International Center of Photography.Once you know Taro's fate, it's harrowing to go through her five blurry contact sheets of the Battle of Brunete, summer 1937. The exhibition doesn't say which one was her last roll. Still, a single shot showing a truck on fire reads as a kind of memorial. (In Paris, where she was buried as an anti-fascist hero, her grave is marked with a stone designed by Giacometti.)

-

Robert Capa, CREDIT: Refugee children drinking milk, Barcelona, October-November 1938 © International Center of Photography/Magnum Collection International Center of Photography.

Robert Capa, CREDIT: Refugee children drinking milk, Barcelona, October-November 1938 © International Center of Photography/Magnum Collection International Center of Photography.After Taro died, Capa left Spain for a while and then returned to cover the Battle of Teruel and, finally, to photograph the Spanish Republican refugees and their exodus from their own country into France. (The fascists won.) Capa's last photographs of the Spanish Civil War, showing families living in internment camps and trudging along the beach from one camp to another, are among his best, right up there with his shots taken on another French beach, five years later—Normandy.

Looking over Capa's pictures, you can see how very good he was at catching people absorbed in the act of reading, running, eating, blowing their noses, or just walking. And nothing says charisma like people doing things with total conviction, fully lost in the act.

-

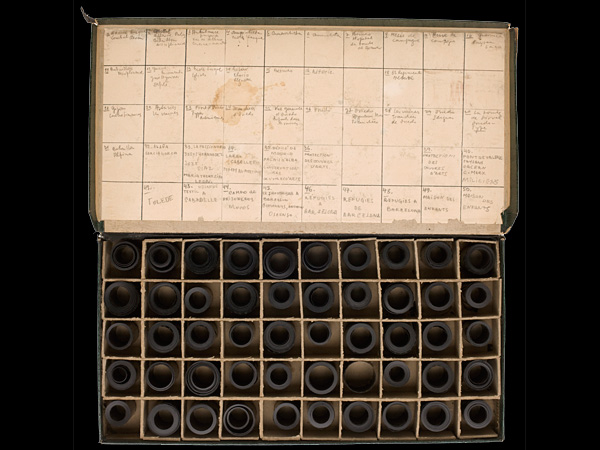

One of three cardboard boxes of the Mexican Suitcase containing Spanish Civil War images by Capa, Chim, and Taro © International Center of Photography.

One of three cardboard boxes of the Mexican Suitcase containing Spanish Civil War images by Capa, Chim, and Taro © International Center of Photography.By this standard, Capa's most charismatic picture is also his best-known, "Falling Soldier," which apparently catches a man in the act of dying. Astute observers will notice that it is not on the wall. But it does figure in this exhibition—in the story of the missing negatives.

By 1939 the war was over, but the saga of the negatives had just begun. Capa returned briefly to his apartment in Paris, then moved to New York, entrusting his belongings, including three boxes holding thousands of negatives, to a friend. After World War II, he never picked up his things. Nine years later, in 1954, he was killed by a land mine while covering the war in Indochina. (Chim died in Suez two years later.) The negatives were all but forgotten.

-

Robert Capa, CREDIT: Exiled Republicans being marched down the beach to an internment camp, Le Barcarès, France, March 1939 © International Center of Photography/Magnum Collection International Center of Photography.

Robert Capa, CREDIT: Exiled Republicans being marched down the beach to an internment camp, Le Barcarès, France, March 1939 © International Center of Photography/Magnum Collection International Center of Photography.Fast-forward a few decades. In 1979, amid accusations that Capa's picture of the falling soldier was a fake, his younger brother, Cornell Capa, the founder of the International Center of Photography, went looking for the negative. Nada.

Finally, though, in 2002 at a Mexico City reception for an exhibition about the Spanish Civil War, the trail for the missing negative heated up. A Mexican filmmaker named Benjamin Tarver told a historian at the reception that he owned a box of negatives that looked a lot like the prints in the exhibition. They'd been passed down to him, he said, from a relative who had been the Mexican ambassador to the Vichy Government in France in 1941 and '42.

In 2007, Tarver produced three contact sheets he had made from the negatives. "Falling Soldier," that charismatic symbol of utter sacrifice, wasn't there. But there were plenty of pictures of rugged soldiers, blazing trucks, and gorgeous photographers. The suitcase had been found. It was time to unpack.