More Than Meets the Eye

-

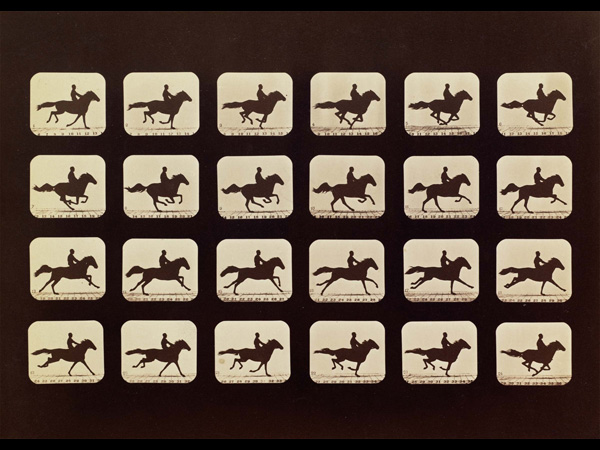

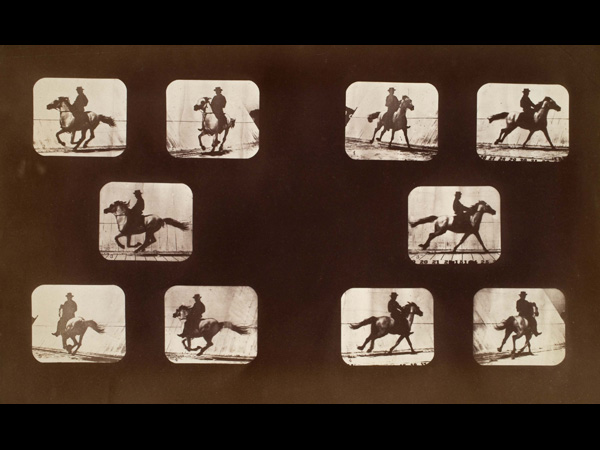

CREDIT: Eadweard Muybridge, Horses. Running. Phryne L. Plate 40, 1879, from The Attitudes of Animals in Motion, 1881. Albumen silver print. Image courtesy the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art, Washington, gift of Mary and Dan Solomon, 2006.

CREDIT: Eadweard Muybridge, Horses. Running. Phryne L. Plate 40, 1879, from The Attitudes of Animals in Motion, 1881. Albumen silver print. Image courtesy the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art, Washington, gift of Mary and Dan Solomon, 2006.You'll be forgiven if you can think only one thought at the mention of Eadweard Muybridge: Yes, when a horse runs, at some point all four legs leave the ground. But Lord help you if that's all you can think after seeing the huge retrospective curated by Philip Brookman at the Corcoran in Washington, D.C., "Helios: Eadweard Muybridge in a Time of Change," a time-and-motion study of the restless man who pioneered high-speed photography.

-

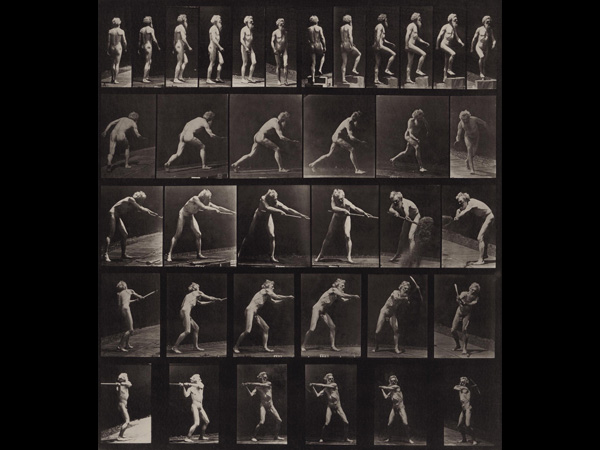

Eadweard Muybridge, CREDIT: a, walking; b, ascending step; c, throwing disk; d, using shovel; e, f, using pick. Plate 521, 1887. Collotype on paper. Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., museum purchase.

Eadweard Muybridge, CREDIT: a, walking; b, ascending step; c, throwing disk; d, using shovel; e, f, using pick. Plate 521, 1887. Collotype on paper. Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., museum purchase.Edward James Muggeridge was born in England in 1830. He moved to San Francisco as a bookseller in the 1850s and took the name Muygridge. He became a photographer in the 1860s and called himself Muybridge. In the early 1870s, he inflated his first name to Eadweard (he liked the way it looked on a plinth). When his only son was born, he merged his name with his wife's (Flora) to name him Floredo. On discovering that Floredo was not his own, he killed the presumed father and was tried, and acquitted, as Eadweard Muybridge. Soon after, he left for Central America as Eduardo Santiago Muybridge. He returned as Eadweard Muybridge and stayed that way until his death in 1904. The name fussing says a lot about the man (pictured here). He cared about appearances, and he was impressively restless.

-

Eadweard Muybridge, Cockatoo; CREDIT: flying. Plate 759, 1887. Collotype on paper. Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., museum purchase.

Eadweard Muybridge, Cockatoo; CREDIT: flying. Plate 759, 1887. Collotype on paper. Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., museum purchase.Restless not just with his name, but with his medium and its stillness. While the world was wowed by photography's ability to record the visible world, Muybridge, it seemed, wanted to capture what the human eye missed—a trot too fast to see, a 360-degree panorama, a rushing waterfall, a bird in flight—and to present these invisibles in all their oddity. To quote Tom Gunning, writing in Time Stands Still: Muybridge and the Instantaneous Photography Moment: "It was Muybridge, more than any other figure, who introduced what Walter Benjamin, decades later, termed the 'optical unconscious,' revealing that much of everyday life takes place beneath the threshold of our conscious awareness."

You might think that Muybridge's aim was scientific or objective—an attempt to see things as they really were—but those terms don't quite capture Muybridge's brand of restlessness. In fact, Muybridge's passion to exceed the limitations of human perception sometimes drove him to some distinctly reckless, eccentric, and unscientific practices.

-

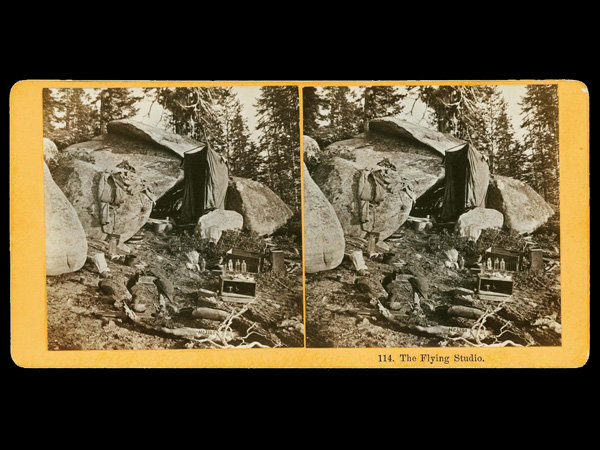

Eadweard Muybridge, CREDIT: The Flying Studio, Photographer's Equipment in the Field (114), 1867. Two albumen silver prints on studio card. Collection of Leonard A. Walle.

Eadweard Muybridge, CREDIT: The Flying Studio, Photographer's Equipment in the Field (114), 1867. Two albumen silver prints on studio card. Collection of Leonard A. Walle.Here, signing his work Helios (a nod to the sun for helping out), Muybridge presents the unsightly mess that was his outdoor workshop, which he called Helios Flying Studio. Despite the name Flying Studio, this image doesn't have much to do with his later interest in motion photography; but it does capture his drive to depict what normally goes unseen. Here he gives us the underbelly of his business—and, indeed, gives it twice. This is a stereo-photograph, which looks 3-D when viewed through stereo goggles. (Make sure to ask to borrow a pair at the Corcoran.)

-

Eadweard Muybridge, CREDIT: Contemplation Rock, Glacier Point (1385), 1872. Two albumen silver prints on studio card. Collection of California Historical Society.

Eadweard Muybridge, CREDIT: Contemplation Rock, Glacier Point (1385), 1872. Two albumen silver prints on studio card. Collection of California Historical Society.In his early years, Muybridge would go to great lengths for a picturesque photo—chopping down trees, adding clouds to his prints, and scrambling to places no sane man would go. Here he is atop Yosemite's Contemplation Rock as an incipient suicide, enjoying the omniscient view while itching to shove off. This picture, implying as it does a push-off and a fall, could serve as a prelude to his motion work. Or maybe as evidence of his insanity. (Two years after it was taken, when Muybridge was tried for murdering his wife's lover, that is exactly how it was used.)

-

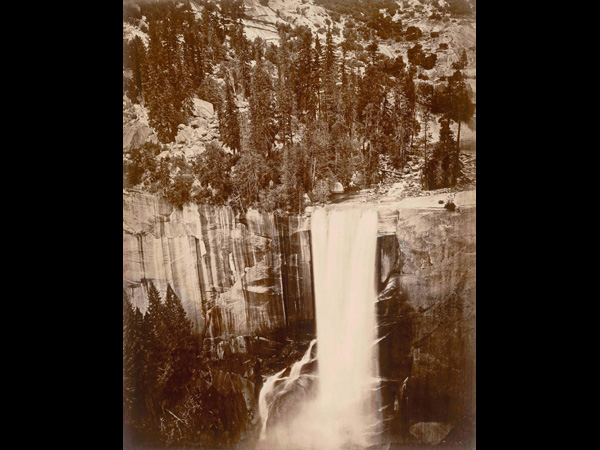

Eadweard Muybridge, CREDIT: Pi-Wi-Ack. Valley of the Yosemite. (Shower of Stars) "Vernal Fall." 400 Feet Fall. No. 29, 1872. Albumen silver print. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Accessions Committee Fund and gift of Jeffrey Fraenkel and Frish Brandt.

Eadweard Muybridge, CREDIT: Pi-Wi-Ack. Valley of the Yosemite. (Shower of Stars) "Vernal Fall." 400 Feet Fall. No. 29, 1872. Albumen silver print. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Accessions Committee Fund and gift of Jeffrey Fraenkel and Frish Brandt.Like his peer and rival, Carleton Watkins, Muybridge produced spectacular, mammoth (17-by-22 inch) prints of Yosemite. In fact, he sometimes duplicated views taken by Watkins, 10 years later. But Muybridge's waterfall pictures are distinctively his. Filmmaker and photographer Hollis Frampton once described them: What he catches is not a cataract but "a tesseract of water … the virtual volume it occupies during the whole time-interval of the exposure." He gives us a picture impatient with its own stillness, drumming its fingers while the water rushes by.

-

Eadweard Muybridge, CREDIT: Occident. Owned by Leland Stanford. Driven by Jas. Tennant, 1877. Albumen silver print on cabinet card. Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University, Stanford Family Collections.

Eadweard Muybridge, CREDIT: Occident. Owned by Leland Stanford. Driven by Jas. Tennant, 1877. Albumen silver print on cabinet card. Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University, Stanford Family Collections.Though plenty successful as a landscape photographer, Muybridge did not become the Muybridge we know now until he met the railroad magnate and racehorse owner (and future founder of Stanford University) Leland Stanford, who asked him in 1872 to capture his horse Occident in motion. According to Brookman, Stanford "wanted to understand the physiology of this movement so as to breed and train horses for greater speed." He also, some say, had made a bet that a running horse's four hooves all leave the ground at the same point.

To do the job, Muybridge took the opposite tack from his waterfall shots, shortening rather than lengthening his exposure time. He claimed he got his money shot—a fuzzy picture of Occident in full motion—in 1872, but the photo no longer exists, if it ever did. The picture here, "a photographic copy of a collage made to look like an original photograph," writes Phillip Prodger, the author of Time Stands Still, came out in 1877.

-

Eadweard Muybridge, CREDIT: Studies of Foreshortenings. Horses. Running. Mahomet. Plates 143–144, 1879, from The Attitudes of Animals in Motion, 1881. Albumen silver print. Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, Va., museum purchase.

Eadweard Muybridge, CREDIT: Studies of Foreshortenings. Horses. Running. Mahomet. Plates 143–144, 1879, from The Attitudes of Animals in Motion, 1881. Albumen silver print. Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, Va., museum purchase.In 1878 Muybridge finally did get a clear photograph of a horse in midstride. Then he began to shoot in sequence. By 1880, Brookman notes, on Stanford's farm in Palo Alto (the future site of Stanford University), Muybridge had rigged up "twenty-four cameras, as well as a clockwork mechanism that synchonized shutters." Muybridge's shot of a running horse with its four legs off the ground and bent under the belly should have settled the horse-hoof matter once and for all, but it didn't. Even after Muybridge's photos came out, the convention of depicting running horses with their legs shooting out in hobby-horse fashion—or ventre à la terre (belly to the ground)—persisted.

-

Eadweard Muybridge, CREDIT: Woman Dancing, 1893. Glass zoopraxiscope disc, paint, metal. By permission of Kingston Museum and Heritage Service.

Eadweard Muybridge, CREDIT: Woman Dancing, 1893. Glass zoopraxiscope disc, paint, metal. By permission of Kingston Museum and Heritage Service.For unbelievers, Muybridge soon had a retort. Undoing the work he had done, he invented a projector that would take the moments he had frozen as photographs and show them reconstituted as short, not-so-seamless animations. The process was hardly objective. Since there was no way to transfer his photographic images to the discs that went into the projector, they had to be copied by hand, in paint. Muybridge, undaunted by the lack of precision, named his device the zoopraxiscope (literally "animal action viewer") and went on a European tour to show it off.

-

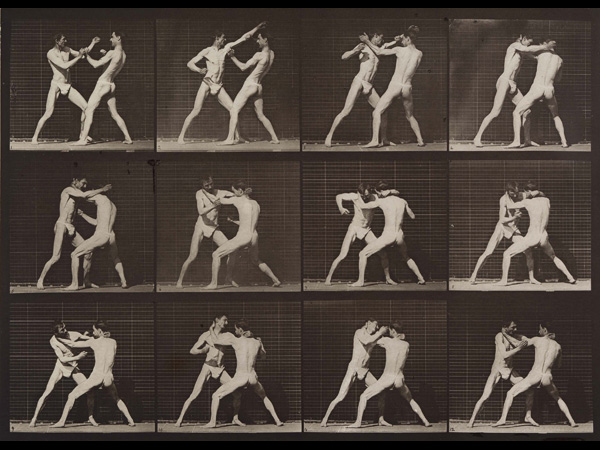

Eadweard Muybridge, CREDIT: Boxing; open hand. Plate 340, 1887. Collotype on paper. Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., museum purchase.

Eadweard Muybridge, CREDIT: Boxing; open hand. Plate 340, 1887. Collotype on paper. Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., museum purchase.While he was in Europe, hobnobbing with artists like Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier and scientists like Etienne-Jules Marey (who was working on his own method for photographing motion), Muybridge's old benefactor was back home undermining his authority. In 1882, Stanford published a scientific treatise, The Horse in Motion, by J.D.B. Stillman, which used Muybridge's pictures without attribution. The situation was clear, Brookman writes: To Stanford, Muybridge was nothing more than "hired help."

Two years later, after trying (unsuccessfully) to sue Stanford, Muybridge found a new patron—the University of Pennsylvania. The painter Thomas Eakins, who owned a set of Muybridge's motion photos and had used them to help his art students correct their paintings, convinced the university's provost, William Pepper, to invite Muybridge to carry out his animal locomotion work there. Muybridge's project was to make a taxonomic study of all kinds of animal and human motion, Marta Braun writes in her catalog essay, "from the movements of the highest subject—the nude male—through women, children, and the crippled, to the lowest, namely, animals." Eakins, who viewed the project as an attempt to build an atlas of true motion for artists, was to supervise.

-

Eadweard Muybridge, CREDIT: Descending stairs, turning, cup and saucer in right hand. Plate 143, 1887. Collotype on paper. Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., museum purchase.

Eadweard Muybridge, CREDIT: Descending stairs, turning, cup and saucer in right hand. Plate 143, 1887. Collotype on paper. Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., museum purchase.It didn't take long, though, for Muybridge's clumsy and unreliable battery of cameras to irritate Eakins, who preferred the neat, single "photographic revolver" devised by the French scientist Marey. While Marey's photographic revolver, with its rotating slotted-disc shutter, shot from a single fixed point and yielded single prints of overlapping images representing different instants, Muybridge's battery of cameras shot from different points and yielded different prints of different instants. (Think of the difference between a panning shot and a tracking shot in film.) Eakins, frustrated with Muybridge's inexactitude—his cameras often misfired, leaving gaps in the sequences—left him to his own devices.

Unsupervised, Muybridge tinkered with his prints, sometimes mixing images from different sequences to make up for gaps. In one finished sequence, Braun notes, a woman begins walking with a bowl in her hands and ends with a jug. Muybridge, a showman more than a scientist, just couldn't help fussing. He was, apparently, more concerned with telling a good story than with ensuring his pictures' objectivity.

-

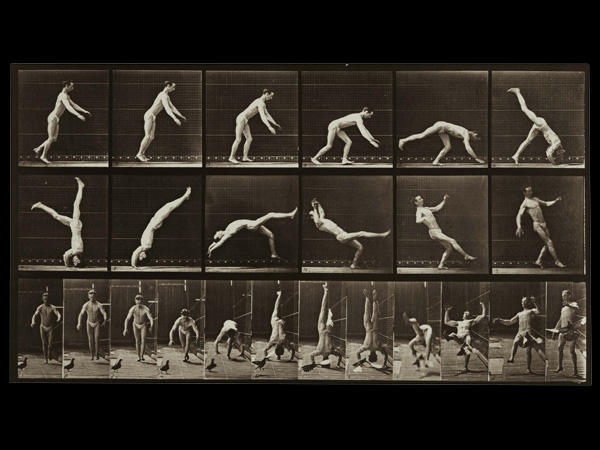

Eadweard Muybridge, CREDIT: Head-spring, a flying pigeon interfering. Plate 365, 1887. Collotype on paper. Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., museum purchase.

Eadweard Muybridge, CREDIT: Head-spring, a flying pigeon interfering. Plate 365, 1887. Collotype on paper. Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., museum purchase.Three years later, Muybridge finished his great opus, Animal Locomotion. It's a veritable Noah's ark, a relentless parade of 20,000 images of animals, human and not, able and crippled, walking and crawling, dancing and flying, running and holding teacups, spanking babies and tossing water, descending and ascending staircases, boxing and chopping. The book was a hit. Muybridge took the best images from it and created discs for his zoopraxiscope, which he showed off at the Chicago World's Fair in 1893. And since 1887, the year Animal Locomotion was published, Braun notes, the book "has never been out of print."

-

Eadweard Muybridge, CREDIT: Movement of the hand; beating time. Plate 535, 1887. Collotype print. Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., museum purchase.

Eadweard Muybridge, CREDIT: Movement of the hand; beating time. Plate 535, 1887. Collotype print. Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., museum purchase.But these pictures are still so strange. Is it because Muybridge's eccentric tastes—so many wrestling men, so many women bearing water—somehow seeped in? Or is it because nature, slowed down and sliced up, simply looks weird? Whatever the reason, this amazing atlas, which has impressed artists from Marcel Duchamp to Francis Bacon, from Cy Twombly to Sol LeWitt, has a kind of voyeuristic and convulsive appeal. It is both attractive and repulsive, mysterious and prosaic. It appears neither natural nor unnatural but rather uncanny, or, as Walter Benjamin put it, "another nature which speaks to the camera rather than the eye."