The Contact Sheet Comes Out of the Closet

-

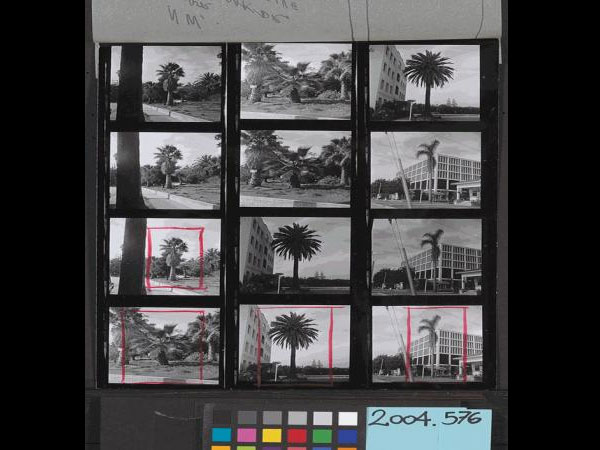

CREDIT: Edward Ruscha, A Few Palm Trees Contact Sheet, 1971. Gelatin silver print, tracing paper and crayon. Sheet: 10 x 8 1/16 in. Other (Tracing paper overlay): 9 3/4 x 8 3/16 in. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase, with funds from The Leonard and Evelyn Lauder Foundation, and Diane and Thomas Tuft.

CREDIT: Edward Ruscha, A Few Palm Trees Contact Sheet, 1971. Gelatin silver print, tracing paper and crayon. Sheet: 10 x 8 1/16 in. Other (Tracing paper overlay): 9 3/4 x 8 3/16 in. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase, with funds from The Leonard and Evelyn Lauder Foundation, and Diane and Thomas Tuft.In New York three museums have brought the contact sheet, once the photographer's secret rough draft, out of the closet. Maybe it's a case of longing for the obsolete, a hunger for something analogue in a digital age. Whatever the reason, it's happening.

At the Whitney, a small show, "A Few Frames: Photography and the Contact Sheet," focuses on artists who have used contact sheets or mimicked their look. The exhibition "Looking In: Robert Frank's The Americans" at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (originally organized by Sarah Greenough at the National Gallery of Art) includes two dozen of the contact sheets Robert Frank used for his 1958 book and they are the most thrilling part of the show. Another exhibition at the Whitney, "Roni Horn a k a Roni Horn," has nothing explicit to do with contact sheets, but nonetheless reflects what I'd call a contact-sheet esthetic, a mode of shooting and showing pictures that's shared by the likes of Walker Evans, Robert Frank, Andy Warhol, and Ed Ruscha.

-

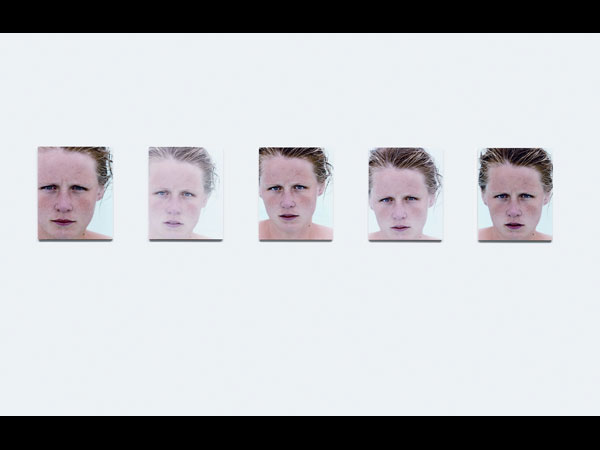

Roni Horn, CREDIT: You are the Weather, 1994-95 (detail). Thirty-six gelatin silver prints and sixty-four chromogenic prints, 10 ½ x 8 ½ in. each. Exhibition copy. © Roni Horn.

Roni Horn, CREDIT: You are the Weather, 1994-95 (detail). Thirty-six gelatin silver prints and sixty-four chromogenic prints, 10 ½ x 8 ½ in. each. Exhibition copy. © Roni Horn.What is a contact sheet esthetic? It is a photographic style that betrays a discomfort with the placidity of a single picture. It is repetitive, deadpan, methodical. It often takes the shape of a grid or a strip. It is a way of turning photography, as Joel Smith, a curator at the Princeton University Art Museum, put it in the catalogue More Than One, into "a sequential, grammatical art," something more akin to film strips or comic strips. It has the pull of a series, the drive of an archive, the thrill of a list – just one damn thing after another.

Roni Horn's work, "You are the Weather," 100 photos each measuring 10 ½ by 8 ½ inches, each taken in the summer of 1994, each focusing on the face of the same female swimmer in Iceland, each face reflecting the day's weather and light as it bounced off the water onto the swimmer's face, definitely has this one-thing-after-another feel and shape. Like "Labor Anonymous," Walker Evans's 1946 photo series showing workers walking past the same wall in Detroit, it is, in effect, a list. And, like Evans, who made a list of types of workers, Horn made a list of words describing both weather and people: bad, balmy, beautiful, bitter, breezy, bright, brisk, brutal, etc. (and that's just the Bs). It is as close as you can get to a contact sheet of words.

-

David Wojnarowicz, CREDIT: Untitled, 1988. Synthetic polymer on two chromogenic prints, 11 x 13 1/4 in. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase with funds from the Photography Committee. Courtesy of The Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W. Gallery, New York, NY.

David Wojnarowicz, CREDIT: Untitled, 1988. Synthetic polymer on two chromogenic prints, 11 x 13 1/4 in. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase with funds from the Photography Committee. Courtesy of The Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W. Gallery, New York, NY.As Horn proves, you don't need to show an actual contact sheet in your work to get the feel of a contact sheet. By the same token, just because you do use a contact sheet in your work doesn't mean it will have that contact sheet vibe. In 1988 David Wojnarowicz used strips from a contact sheet. Yet the object he made (in the show "A Few Frames") feels nothing like a contact sheet. Instead, it tells a story. The frame tale – and the actual outline of this shaped work – is two men kissing, and if you look closely at the individual contact-sheet images that appear within those kissing outlines, you'll see they're like illustrations: The pictures within the boundaries of one man's outline tell one man's tale. The other half is about the other man. Or so it seems. In other words, here the contact sheet has been pressed into narrative service. Taken on its own, it is without motive.

-

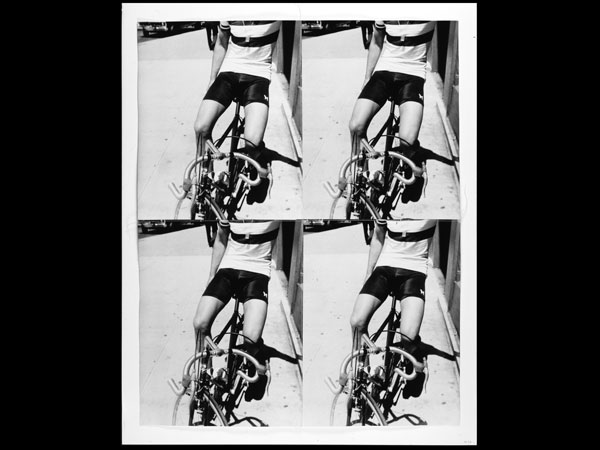

Andy Warhol, CREDIT: Untitled (Cyclist), c. 1976. Four gelatin silver prints stitched with thread. Sheet: 27 3/8 x 21 5/8in. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; gift of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts and purchase, with funds from the Photography Committee. © 2009 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Andy Warhol, CREDIT: Untitled (Cyclist), c. 1976. Four gelatin silver prints stitched with thread. Sheet: 27 3/8 x 21 5/8in. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; gift of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts and purchase, with funds from the Photography Committee. © 2009 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York."Untitled (Cyclist)," an Andy Warhol piece from 1976 (in "A Few Frames"), is the exact opposite. It has the energy of a contact sheet, though it's actually a carefully composed object containing no real contact sheets. With string, Warhol stitched together four identical gelatin silver prints. By repeating the image of a cyclist whose head had been lopped off by the edge of the film frame, Warhol amped up the machine-like anonymity of the photo. Bike and body become one. And both become part of a buzzy pattern that makes it hard to focus on a single image.

-

CREDIT: Edward Ruscha, Mock Up #19 (South West Corner of Graciosa Drive and Beachwood Drive), 1971. Gelatin silver print, tracing paper, pigment, pencil, and ink on board. Board: 11 x 8in. Other (Tracing paper): 8 1/8 x 5 1/2in. Image: 7 x 5in. (17.8 x 12.7cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase, with funds from The Leonard and Evelyn Lauder Foundation, and Diane and Thomas Tuft.

CREDIT: Edward Ruscha, Mock Up #19 (South West Corner of Graciosa Drive and Beachwood Drive), 1971. Gelatin silver print, tracing paper, pigment, pencil, and ink on board. Board: 11 x 8in. Other (Tracing paper): 8 1/8 x 5 1/2in. Image: 7 x 5in. (17.8 x 12.7cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase, with funds from The Leonard and Evelyn Lauder Foundation, and Diane and Thomas Tuft.Some artists, no matter how much purifying and processing they do, cannot shake that raw, deadpan spirit out of their work. Ed Ruscha, the creator of such supremely mundane books as Every Building on the Sunset Strip (1966), Twentysix Gasoline Stations (1963), Thirtyfour Parking Lots (1967) and A Few Palm Trees (1971), is one of them. In the show "A Few Frames," you can see the purifying steps he took to get to A Few Palm Trees.

First he wandered around Southern California shooting palm trees in front of buildings. Then, from his contact sheets, he chose a few palm trees, 14 of them, drawing orange or red crayon boxes to indicate not only which images he wanted from the lineup but also how he wanted to crop them. After that he made prints of his chosen trees and covered them with tracing paper. He indicated with white ink how he'd silhouette them. His finished object, a book of offset prints of singular palm trees on vellum, has the precious, old-fashioned look of a botanical manual, but also the hip, deadpan quality of a contact sheet.

-

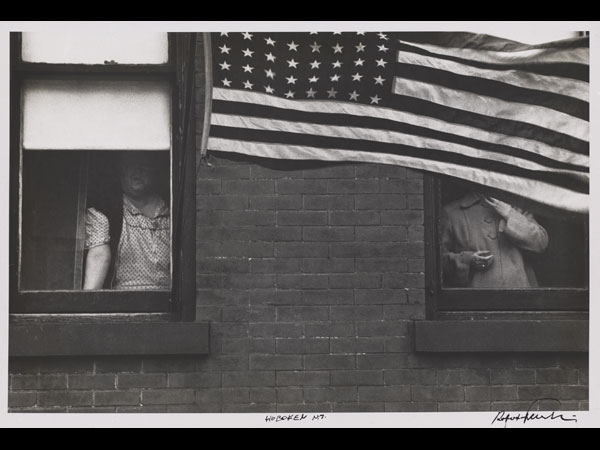

Robert Frank, CREDIT: Parade—Hoboken, New Jersey, 1955. Gelatin silver print, 8 3/8 x 12 3/4 in. Private collection, San Francisco. © Robert Frank, from The Americans.

Robert Frank, CREDIT: Parade—Hoboken, New Jersey, 1955. Gelatin silver print, 8 3/8 x 12 3/4 in. Private collection, San Francisco. © Robert Frank, from The Americans.No one embodies the contact sheet vibe quite as completely as Robert Frank. Many of his photographs have serial imagery in them, many are rough in feel, and many show motion. As Sarah Greenough notes in the catalogue for the Frank exhibition now at the Met, Frank started to disdain the sentimentality of the perfect picture even before he started making The Americans. "I went away from my early lyrical images," Frank said, "because it wasn't enough anymore. I had used up the single, beautiful image." Unlike Frank's mentor Walker Evans, Greenough writes, "he sought, as he simply said, 'things that move.'"

In the end, Frank did, of course, choose single images for The Americans, narrowing his field of photos from the 27,000 that he shot in 1955 and 1956 to just 83. But his careful sequencing of the photographs was designed to set up "some kind of rhythm" and he proved that choice shots need not be precious shots.

If you compare Frank's contact sheets with his chosen images, what's striking is not how much better his picks are than his rejects but rather how some of his most iconic images resemble contact sheets in microcosm, presenting one thing after another—racks of magazines, grids of windows, lines of people. Take "Parade Hoboken, New Jersey." It's not only a single image but also a kind of contact sheet containing two separate images, divided by a flag.

-

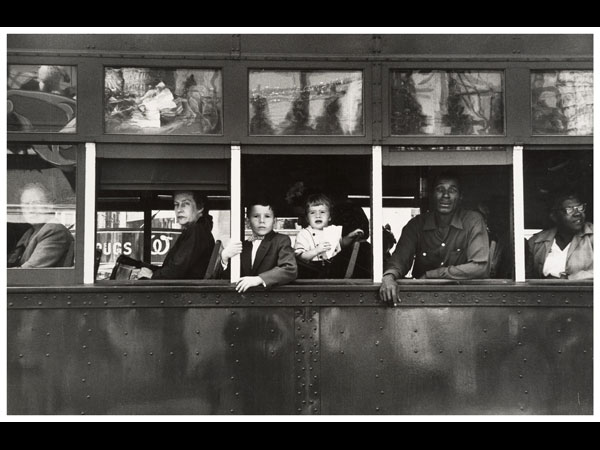

Robert FrankCREDIT: , Trolley—New Orleans, 1955. Gelatin silver print, 8 5/8 x 13 1/16 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gilman Collection, purchase, Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee. Gift, 2005. © Robert Frank, from The Americans.

Robert FrankCREDIT: , Trolley—New Orleans, 1955. Gelatin silver print, 8 5/8 x 13 1/16 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gilman Collection, purchase, Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee. Gift, 2005. © Robert Frank, from The Americans.Frank had a knack for capturing loneliness in motion and crowds of isolates: so many people, so many worlds. "New Orleans Trolley Car," the cover photo for the first American edition of The Americans in 1959, is the best example. It can be read, of course, as a picture of a trolley full of disconnected passengers, segregated by race, whites in front, blacks in back. As Greenough writes, "Each of the windows of the trolley presents a carefully delineated, separate portrait." But if you look carefully, you'll also see strips of blurry images above and below. The whole photo resembles nothing so much as a working contact sheet with three horizontal strips, each containing small images within it.

-

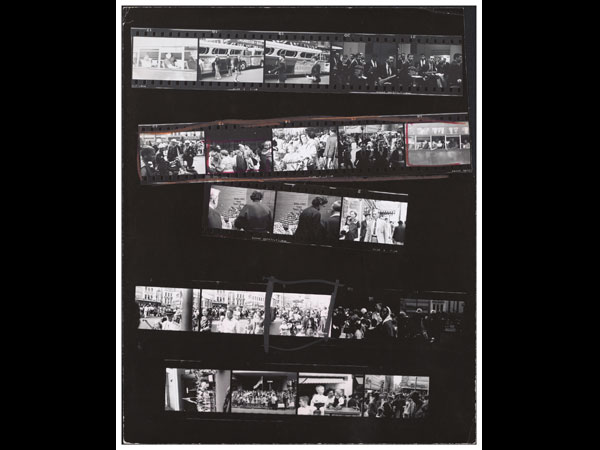

Robert Frank, CREDIT: Guggenheim 340/Americans 18 and 19—New Orleans, 11/1/1955, contact sheet, 10 x 8 1/16 in. National Gallery of Art, Washington, Robert Frank Collection, gift of Robert Frank. © Robert Frank.

Robert Frank, CREDIT: Guggenheim 340/Americans 18 and 19—New Orleans, 11/1/1955, contact sheet, 10 x 8 1/16 in. National Gallery of Art, Washington, Robert Frank Collection, gift of Robert Frank. © Robert Frank.Decades after The Americans was published, Frank became uncomfortable with its fame and tried to undo it. He made a stack of his old prints, including some from The Americans, then had a friend drill holes through the stack, then crucified it on a board. As if to drive home the point that his photos had become a sacred cow, the top picture on the ruined stack is of a young bull gored by a dagger. And as if to memorialize, or lampoon, his long process of editing down the contact sheets of The Americans, he lassoed and bound the gored stack with a wire that was bright orange, just like his editing crayon. Yes, even when attempting to destroy own work, Frank could not help treating it all like a contact sheet.

Now even the roughest image isn't safe from idolization. Not only is Frank's crucified stack on view at the Met, but even the homely contact sheet, once an object not much more prized than a shopping list, has become an icon, a relic of a day when covering your tracks, your touch, and your thoughts wasn't nearly as simple as clicking a button.