The Found Poetry of Postcards

-

Installation view, detail © the Metropolitan Museum of Art, N.Y.

Installation view, detail © the Metropolitan Museum of Art, N.Y.All those baby-blue skies, all those tan sandy roads, all those quiet brick buildings, all those zippy vanishing points! Dazzling was the first word that popped into mind when I saw "Walker Evans and the Picture Postcard" at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The shimmer of repetition was so blinding that, at first, it was impossible to approach the grids of cards to study their details. Was that the way Evans saw the collection he amassed over 60 years? Unlikely.

-

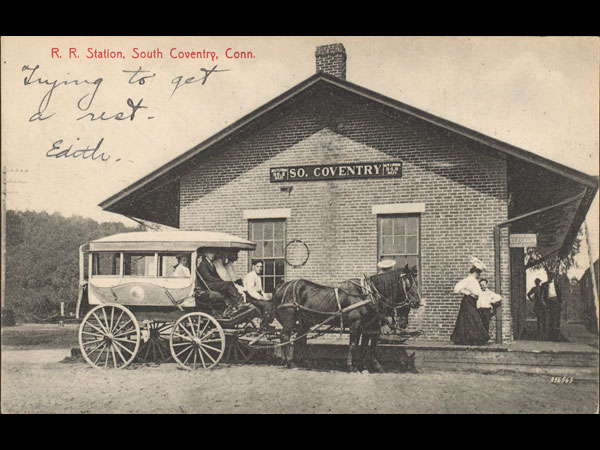

CREDIT: Unknown artist. R.R. Station, South Coventry, Conn., 1900s. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Walker Evans Archive, 1994.

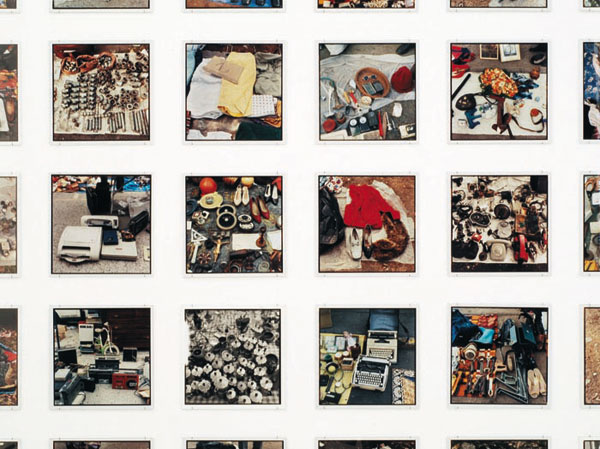

CREDIT: Unknown artist. R.R. Station, South Coventry, Conn., 1900s. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Walker Evans Archive, 1994.Evans did not have a razzle-dazzle eye. He collected bottle caps, pull tabs from tin cans, signs, and, at the end of his life, driftwood (all shown in the exhibition). He liked postcards for their lack of pretension (he called them "folk documents") and their brief messages ("How about yesterday," one reads).

-

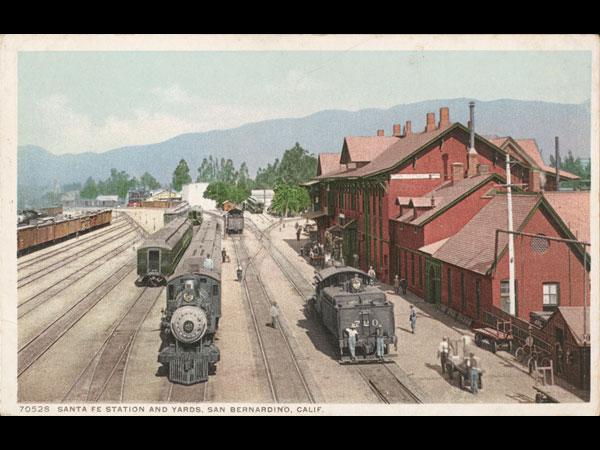

Unknown artist. CREDIT: Santa Fe Station and Yards, San Bernardino, Calif., ca. 1910. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Walker Evans Archive, 1994.

Unknown artist. CREDIT: Santa Fe Station and Yards, San Bernardino, Calif., ca. 1910. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Walker Evans Archive, 1994.He started collecting when he was 12, and when he got older, his friends, including Lee Friedlander and Helen Levitt, sent him the kinds he liked. (The show has a nice selection of his postcard correspondence, including one of a glass-bottom boat from Robert Frank and, from Diane Arbus, a flatly funny line on a blank card: "I tried making potatoes like yours but they werent.") Evans filed his postcards by subject behind blue or tan index cards penciled with headings: "Street Scenes," "Factories," "Automobiles," "Detroits" (his favorite postcard company), "Summer Hotels," "Railroad Stations," etc. (Many of his index cards, luckily, make it into the show; they are the hub of each grid of like-themed picture postcards.)

-

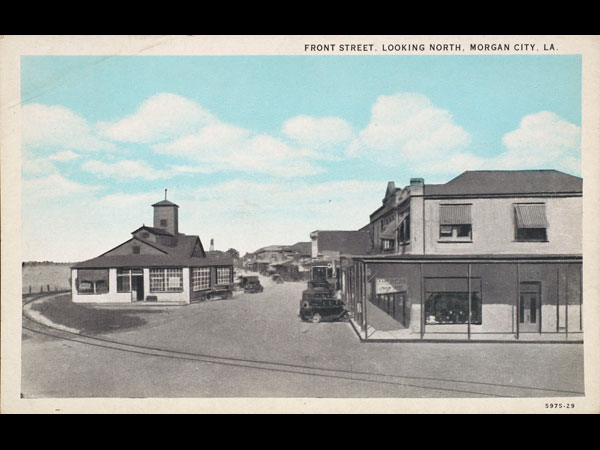

Unknown artist. CREDIT: Front Street, Looking North, Morgan City, La., 1929. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Walker Evans Archive, 1994.

Unknown artist. CREDIT: Front Street, Looking North, Morgan City, La., 1929. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Walker Evans Archive, 1994.In 1964, when Evans gave a slide lecture at Yale University about his postcard collection, his theme was "lyric documentary"—a quality that, you might say, is the opposite of dazzling. Evans spent his lecture (the transcript is in the Met catalog) trying to define the nonarty sort of beauty that comes out unintentionally when a photographer, writer, or draftsman is absorbed in exploring a subject.

"Leonardo for me is the father of what I call the 'lyric documentary,' " Evans said, talking about Da Vinci's medical, mechanical, and embryological drawings: "that line and that mental approach, that scientific curiosity and that cleanliness, and that detachment of his seemed to me documentary. And, of course, his line is lyric." Almost by accident, his drawings are lyrical.

-

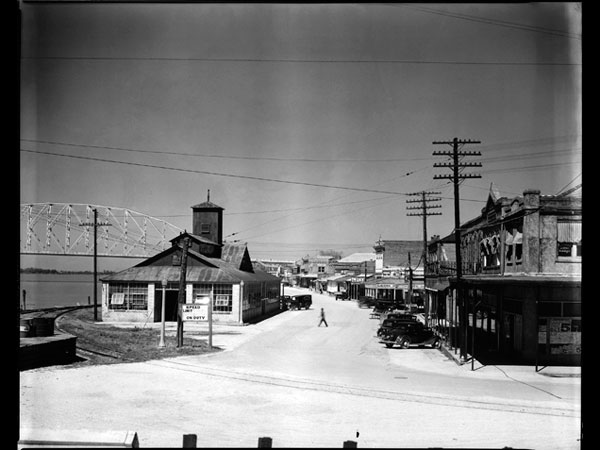

Walker Evans. CREDIT: Street Scene, Morgan City, La., 1935. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Walker Evans Archive, 1994

Walker Evans. CREDIT: Street Scene, Morgan City, La., 1935. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Walker Evans Archive, 1994Evans listed other accidental lyric artists: "Constable, Goya, Degas, very much Guys, Daumier, very, very much Lautrec, our own Hopper. And Shahn. …" He mentioned Palladio and Audubon. In literature he listed Joyce, Agee, Nabokov in The Gift, and Henry James, sometimes. In photography, Evans named, above all, Atget, the chronicler of turn-of-the-century Paris; Brady and Gardner, the Civil War photographers; Alvin Langdon Coburn, one of Henry James' favorites; and, last of all, himself. (In his own photos he sometimes duplicated the exact scenes of postcards.)

Notably, Evans left out Stieglitz: "Now I would mention Alfred Stieglitz as somebody who tries a little bit too hard to get this. And I would call that 'decadent lyric' … because he is pushing for it very hard. No, he's going after cloud and nature and talking about really how God was behind his camera or something. Everything he did, at least to me, implied this, and it made me very angry."

-

Zoe Leonard, CREDIT: Analogue, 1998-2007. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, Germany. Photograph by Bill Jacobson Studio, N.Y. Installation view from the exhibition "Zoe Leonard: Derrotero," Dia at the Hispanic Society of America.

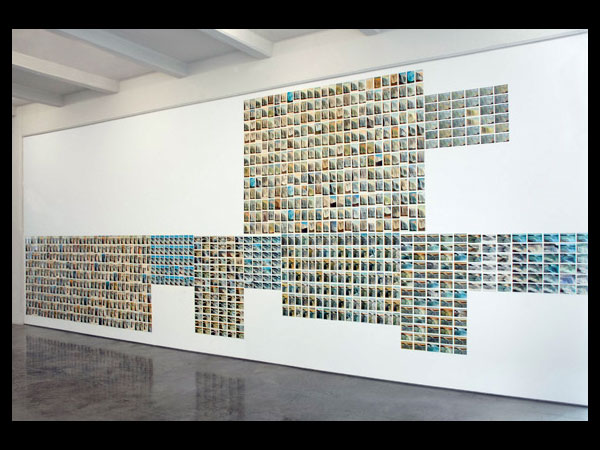

Zoe Leonard, CREDIT: Analogue, 1998-2007. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, Germany. Photograph by Bill Jacobson Studio, N.Y. Installation view from the exhibition "Zoe Leonard: Derrotero," Dia at the Hispanic Society of America.What would Evans have made of contemporary photographer Zoe Leonard? In some respects, she is almost a Walker stalker. Between 1998 and 2007, using a vintage 1940 camera, she took a series of plain, frontal, color and black-and-white pictures of funky signs, storefronts, stacks of merchandise, and clothes racks—all Evans-like subjects—in New York and in Mexico, Poland, and Uganda. (The resulting work, "Analogue," is now part of an exhibition at the Hispanic Society in New York City.)

And then she began collecting postcards. Where Evans collected his 9,000 postcards over a lifetime for no specific purpose, Leonard bought 4,000 postcards of Niagara Falls quickly, in a year's time, mostly via the Internet, for an installation now on view at Dia:Beacon. Evans sorted his by subject in boxes. She has arranged hers on the walls of Dia by motif—Prospect Point, American Falls, Rock of Ages, Cave of the Winds, Horseshoe Falls, Table Rock—in a series of linked, stair-stepping grids.

-

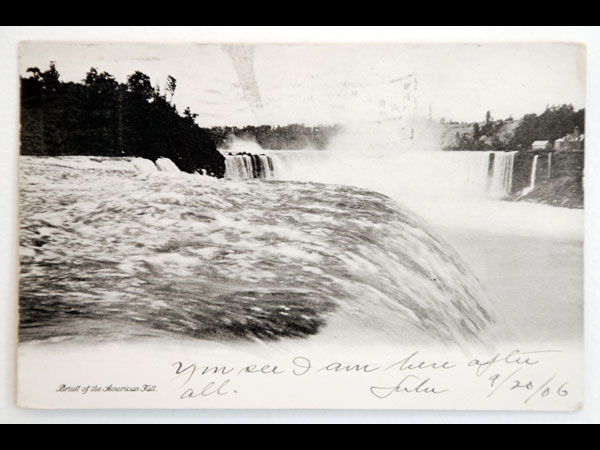

Zoe Leonard, CREDIT: You see I am here after all, 2008 (detail). Installation at Dia:Beacon, Beacon, N.Y. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, Germany. Photograph by Francesca Esmay.

Zoe Leonard, CREDIT: You see I am here after all, 2008 (detail). Installation at Dia:Beacon, Beacon, N.Y. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, Germany. Photograph by Francesca Esmay.Leonard's postcard collection begs for comparison with Evans'. Does it have that Evans-escent quality or not? Some of Leonard's individual postcards do indeed possess their own deadpan lyricism. And the title of Leonard's show, "You see I am here after all," does, too. It comes from a handwritten message taken straight from the bottom of a black-and-white postcard of the American Falls. The words are plain, resigned, and witty without trying to be.

-

Zoe Leonard, CREDIT: You see I am here after all, 2008. Installation at Dia:Beacon, Beacon, N.Y. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, Germany. Photograph by Bill Jacobson, N.Y.

Zoe Leonard, CREDIT: You see I am here after all, 2008. Installation at Dia:Beacon, Beacon, N.Y. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, Germany. Photograph by Bill Jacobson, N.Y.But the exhibition "You see I am here after all" is not about the individual cards. It's about their installation on the wall. By arranging her cards into a shape that is both rigid and gawky, Leonard overrides any sense one might get from the individual cards. (Indeed, the title card of the show is lost in the shuffle.) And yet the installation, for all its apparent documentary drive, goes nowhere definite. Maybe Leonard is, as curator Lynne Cooke writes, trying to show how "cultural conventions" have defined our natural world. Or how mass-produced artifacts, like postcards, can suck the sublime out of even the most awesome subjects. It is hard to tell from the exhibition. And the cards are in no position to speak for themselves. Many are positioned too high up on the wall to see them or their captions. A child looking over the wall of postcards voiced my sentiments exactly: "Is that a shape?"

-

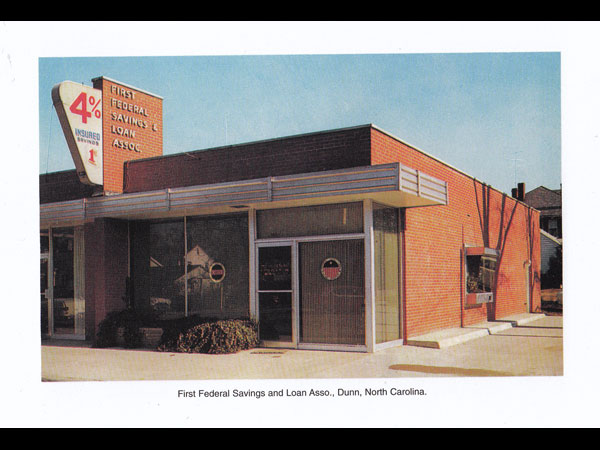

From CREDIT: Boring Postcards USA by Martin Parr.

From CREDIT: Boring Postcards USA by Martin Parr.Picture postcards are contradictory things. On the face of it, they're just cheap mass-produced objects, nothing more than testaments about the culture that made them. Yet, because they are photographs, they also bear the unique stamp of their time and the place. And when someone writes on them, mails them, and, yes, even collects them, they acquire another layer of aura. Thus, not all mass-produced postcards or postcard collections are equal. Some sing out more clearly than others.

Consider, for instance, the collection of Martin Parr, a British documentary photographer known for his comical pictures of consumer culture. His book, Boring Postcards USA (which follows the book Boring Postcards), offers the homeliest of midcentury American subjects: interstate highways, toll plazas, car washes, banks, motels (inside and out), and diner food. Despite and because of the consistent deadliness of his chosen subjects, Parr's collection has an aura. It ain't lyrical, exactly, but there it is.

-

Unknown artist. CREDIT: Main Street, Showing Confederate Monument, Lenoir, N.C., 1930s. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Walker Evans Archive, 1994.

Unknown artist. CREDIT: Main Street, Showing Confederate Monument, Lenoir, N.C., 1930s. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Walker Evans Archive, 1994.What of Evans' own collection? It's weird that Evans found some of the individual cards in it lyrical. Few have that accidental, un-thought-out quality that he claimed they did. Many are stagey, upbeat, and a little fakey. (Oddly, he particularly liked the hand-colored cards.) The only consistently lyrical elements in them are the occasional messages scrawled on the fronts, which Evans (as the curator of the show, Jeff L. Rosenheim, notes) did appreciate "as a kind of found poetry—allusive, egalitarian, and vernacular." Still, Evans' collection as a whole—at least as shown at the Met—has a propulsive energy, an optimistic, Whitman-esque poetry radiating from its prosaic body of interests.

-

Walker Evans, CREDIT: View of Easton Pennsylvania (variant), 1935. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, purchase, the Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 1991.

Walker Evans, CREDIT: View of Easton Pennsylvania (variant), 1935. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, purchase, the Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 1991.Around 1936, Evans began making his own postcards by printing cropped versions of the photos he took for the Resettlement Administration. (The Museum of Modern Art was going to publish sets of them but never did.) What's curious is that Evans didn't come close to matching the look of most of the postcards he amassed. His own attempts at picture postcards are black-and-white, totally unstaged, and rather sad. They have that backward-looking, been-there quality you rarely see in postcards. To quote the Met's wall text, they capture the present "as if it were already past." In short, they're more lyrical than the ones he collected.

I don't know what Evans would have made of Zoe Leonard's "You see I am here after all," but I think he would have liked her title. It is both vernacular and allusive, evoking, probably by accident, the Latin words "Et in Arcadia Ego" ("Even in paradise I exist," where I is Death). It gives an elegiac spin to tourism and a touristy spin to elegy. And maybe it even captures the voice of an unpretentious postcard that—beyond all expectations—finds itself in a museum.