The Incredibles

-

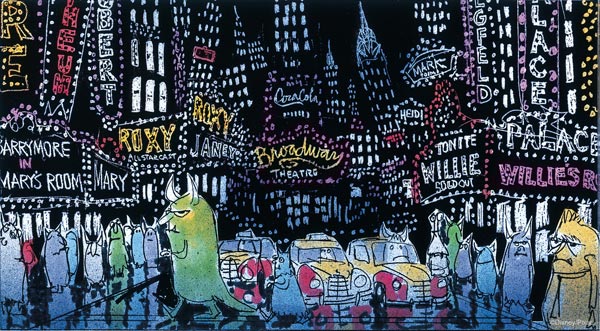

Harley Jessup, CREDIT: Downtown Monstropolis, Monsters, Inc. © Disney/Pixar. Image courtesy Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Harley Jessup, CREDIT: Downtown Monstropolis, Monsters, Inc. © Disney/Pixar. Image courtesy Museum of Modern Art, New York.MoMA's new exhibition Pixar: 20 Years of Animation (Dec. 14, 2005 to Feb. 6, 2006) doesn't belong in one of the world's major art museums. In fact, a show about a company that makes animated films shouldn't be in an art museum at all. Not because the sprawl of popular culture expanding into hallowed cultural spaces pollutes the value of serious art. If you believe that comics and cartoons—or even urinals on museum walls—threaten the immortal beauty and meaning of a Rembrandt or a Matisse, then your relationship to high culture is a lot less secure than you think. No, the Pixar show shouldn't be in an art museum because sophisticated animated films like Finding Nemo and The Incredibles—Pixar's two most successful movies of the six it's made so far—are not so much visual works as visual candidates for the occupation of a literary void. For some years now, a number of American novelists have offered mostly contrived stories and cartoonish characters—Jonathan Safran Foer's or Nicole Krauss' cloying caricatures, Jonathan Franzen's simile-heavy stereotypes, Salman Rushdie's failed attempts to revitalize the novel with deliberately flat characters (they read instead like the author's failures of empathy), and so forth. Maybe one reason audiences flock to Pixar and other animated films is that they'd rather experience cartoon figures who operate with complex psychologies than unachieved literary characters who act like cartoons.

-

Teddy Newton,CREDIT: Edna Mode (aka "E"), The Incredibles © Pixar.

Teddy Newton,CREDIT: Edna Mode (aka "E"), The Incredibles © Pixar.The best thing about the Pixar show is that throughout its duration, MoMA will present screenings of Pixar's films. That's not to say that the two galleries of drawings, pastels, collages, urethane sculptures, and storyboards—consecutive sketches illustrating the scene-by-scene action of the film—aren't worth lingering in. Our dominant culture is visual, not literary, and it's interesting to see the inner workings of an increasingly popular and versatile visual genre. As you follow the mechanics of telling an animated story, you can see why intelligent cartoons might well displace literary fiction. When we disparage a poorly developed character in a novel by calling him a "cartoon," we're saying that he's too general and abstract to be believable as a person. But the generality of a complicatedly scripted animated figure has the reverse effect. As the character deepens from type into a concrete figure, symbolic and specific meanings fuse. Novelists have become increasingly self-conscious about psychological categories. Cartoons, however, offer an evocative externality. The viewer supplies the interiority himself—out of his own.

Image courtesy Museum of Modern Art, New York. -

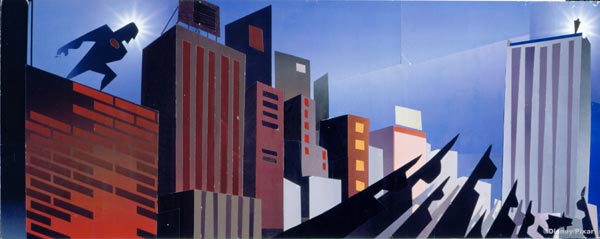

Teddy Newton, CREDIT: The Jumper, The Incredibles © Disney/Pixar. Image courtesy Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Teddy Newton, CREDIT: The Jumper, The Incredibles © Disney/Pixar. Image courtesy Museum of Modern Art, New York.Of course, long before Steve Jobs bought Pixar in 1986 from Lucasfilm—where Pixar had been the computer division—and set it up as an independent company, Disney was making animated movies. But what a difference between the old and the new animation! It's because of Disney that we think of animated movies as children's fare, yet Pixar's roots are in the more sophisticated tradition of DC and Marvel comics. Buried in the dual nature of the comic-book creation of Clark Kent/Superman is a provocative contest between superior human qualities and the ordinary virtues of democratic man—"Superman" was where Nietzsche tussled with Walt Whitman. Pixar embarked more from such playful insinuations than from Disney "magic." It brought mainstream, commercial animated film into the realm of the graphic novel. The Incredibles—a story about superheroes who have to hide their powers in order to avoid the envy and resentment of their fellow citizens—is both a nod to Superman's hidden dilemma and an infinitely interpretable parable about the limits of our so-called meritocracy. That's about as far from Mickey, Donald, and Co. as you can get. And it's why Pixar is more historically significant than, say, Dreamworks, which hasn't produced films of similar depth.

-

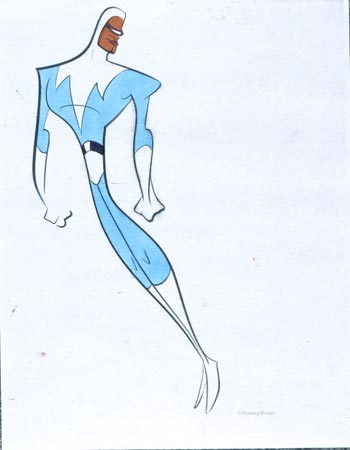

Teddy Newton, CREDIT: Frozone, The Incredibles © Disney/Pixar.

Teddy Newton, CREDIT: Frozone, The Incredibles © Disney/Pixar.The Incredibles doesn't only offer playful, ingenious social commentary. Its very nature as a cartoon reflects some intriguing social trends. From every corner of society, we hear the cries of self—memoirs, confessional talk shows, movies in which the camera goes from one screen-filling close-up to another, which is sort of like going from one memoir to another. No wonder it's so hard for novelists to depict interiority nowadays—what goes on inside people is so much talked about outside, in public, and so prized a trait that it has become banal. Articulate animated figures, on the other hand, don't so much caricature the human figure as defamiliarize it. Looking at a cartoon character, you have to deduce human qualities and then arrive at your own notion of a particular human being. The symbolic types in myths and fairy tales provoke the same response. Like such types, animated figures are not personalities. Rather, they are ideas about being a person. They are anti-personalities. This implicit criticism of self-centered society might be why animated films seem to lend themselves most easily to satire: The Incredibles (quasi-satirical as it is); The Simpsons; Team America: World Police; South Park; The Boondocks, etc. In fact, there are more animated social and political satires around now than satirical novels, plays, or even films.

Image courtesy Museum of Modern Art, New York. -

Simón Vladimir Varela, CREDIT: Sharks, Finding Nemo © Disney/Pixar. Image courtesy Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Simón Vladimir Varela, CREDIT: Sharks, Finding Nemo © Disney/Pixar. Image courtesy Museum of Modern Art, New York.Pixar is an immensely lucrative film company. Its first six feature films grossed more than $3 billion. And so far as I know, praise for the company's movies has been universal and unadulterated. But Pixar's status as a profit-producing prodigy is a kind of rub. The peril of animated films lies in the corporate nature of the enterprise. An utter dependence on leading-edge technology means that the animation company is determined by the kind of competitive-minded, innovation-for-innovation's-sake imperative that is more familiar to businessmen than to artists. And soaring profits creates pressures to keep them soaring. It's significant that Pixar began as a computer-graphics outfit and then developed into a firm that made commercials for companies like Tropicana, Listerine, and LifeSavers. Pixar didn't come into its own as a movie-making enterprise until it joined up in 1991 with Disney, who helped finance the movies and, crucially, provided distribution deals. (At the moment, Pixar's current deal with Disney is scheduled to expire with the release of Cars in 2006.) Any large-scale collaboration that has to keep pace with rapidly changing technology and is driven by visions of unimaginable profits has crucial limitations. It is going to be wary of ideas that either are irrelevant to technological innovation or threaten the by-now exorbitant expectations of investors. That's why Pixar's creativity may be about to hit a glass ceiling.

-

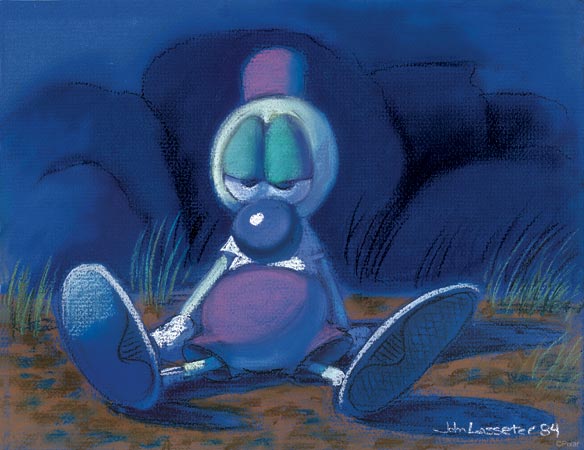

John Lasseter, CREDIT: André, The Adventures of André and Wally B. © Pixar. Image courtesy the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

John Lasseter, CREDIT: André, The Adventures of André and Wally B. © Pixar. Image courtesy the Museum of Modern Art, New York.Still, Pixar's success at making literate cartoons is a seminal moment in the culture. American life is so crazy-quilted that animation's figures—these symbolic particularities—might be the only way to encompass not only the way we live, but also thoughts and feelings that have become lost to us in all the mad velocity we are surrounded by. Go ahead, laugh, but Pixar's creations have a lot to teach novelists. They might start with Finding Nemo—that fairy-tale-like story about the death of a mother, the loss of a home, the cruelty of the outside world (and the occasional kindnesses that make the cruelty even harder to bear), and a father's and son's search for each other. Yes, yes, they're fish. But the Greek gods who transformed themselves into animals, and the Greek poets who invented those transformations, did so in order to refresh the imagination by slipping into something a little less comfortable and a little more strange. Intelligent cartoons are yet another powerful form of imaginative refreshment. They'll serve until words learn a new lesson from images and come fully to life again.