Anthony Bourdain very nearly ate his first meal in Japan at a Starbucks. As he recounts in Kitchen Confidential, the 2000 memoir that made him a celebrity, he had been dispatched in 1998 by the owners of Les Halles, the New York restaurant where he was executive chef, to open a Tokyo branch. Hungover and bleary-eyed at 5 a.m., the man who would one day preach the gospel of culinary adventurism—but at the time had almost no experience with international travel—“didn’t have the nerve” to go into a noodle shop, being “acutely aware of how freakish and un-Japanese I looked.” He writes, “The prospect of pushing aside the banner to one of these places, sliding back the door and stepping inside, then squeezing on to a stool at a packed counter and trying to figure out how and what to order was a little frightening.” Thankfully for him—and the rest of us—fortified by a latte, he summoned the nerve to go out and slurp down some soba.

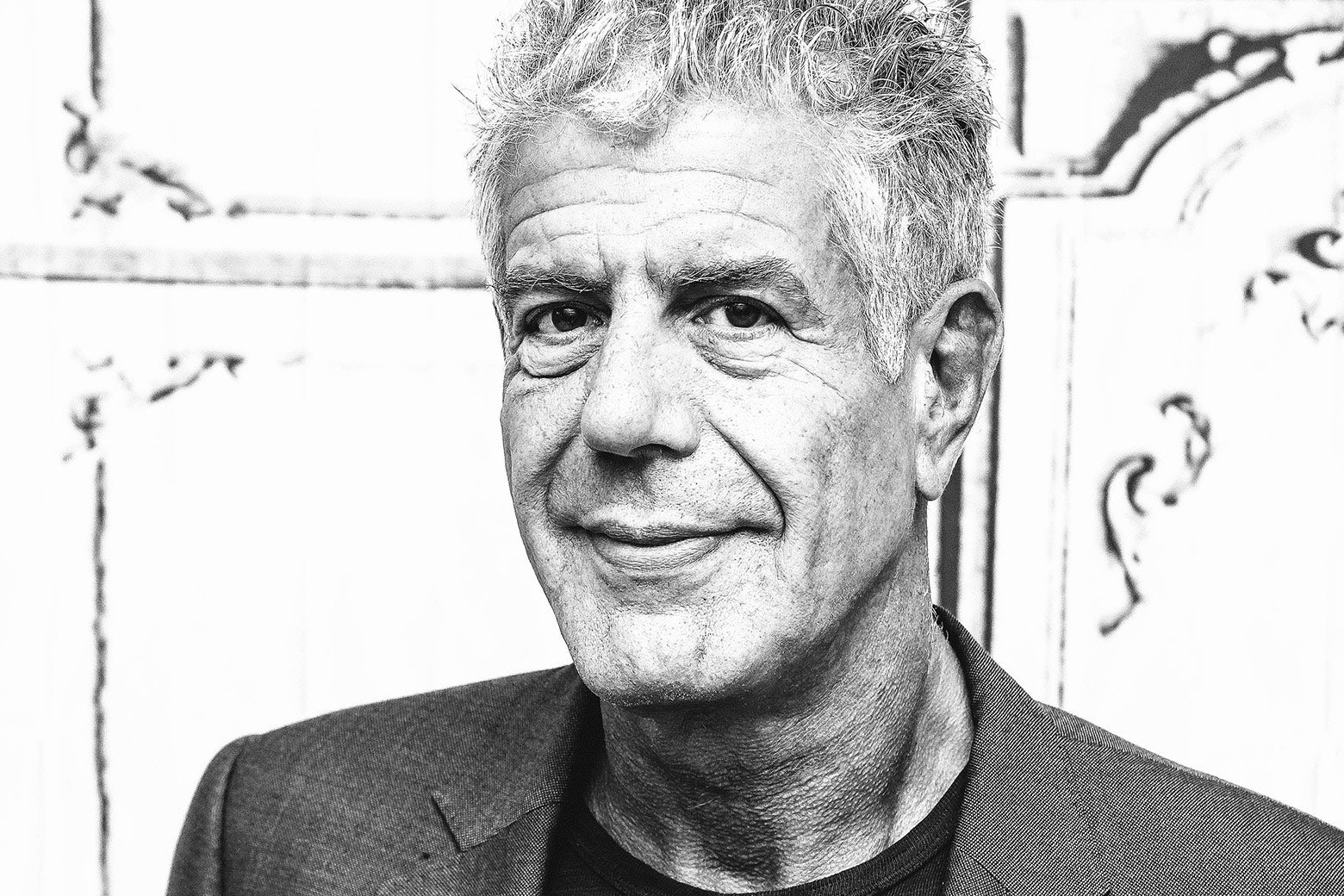

Someone who looked and acted like Bourdain, who died at the age of 61 in an apparent suicide in France while working on an episode of his show, was never going to blend in anywhere—maybe parts of New York—and that became even more the case as his fame grew. But the lesson of his shows, which I’ve watched over the years on both the Travel Channel and later on CNN, was that blending in wasn’t the point. This may sound like a grandiose claim for a guy best known for stuffing his face and making wisecracks, but Bourdain presented a model of how Americans could act in the world: open-minded, always curious, and unafraid to sometimes look ridiculous.

His persona was a refreshing alternative to the familiar archetypes of Americans abroad—flak-jacketed war correspondent, selfless aid worker, pampered tourist, blissed-out enlightenment-seeking backpacker. Bourdain showed how you could be radically open to new experiences while still being basically yourself. While profoundly aware, particularly on his CNN show, of past U.S. misdeeds and how his country is perceived in the world, he was undeniably American too.

Bourdain could serve up food porn with the best of them, but also deserves credit for smuggling in-depth features on countries that rarely rate for TV-news coverage, like Congo, Myanmar, and Ethiopia, onto prime-time television. According to a New Yorker feature last year, a number of staffers at the Obama White House had been unaware of the extent of the problem of unexploded U.S. ordnance in Laos until Bourdain featured it on his show. Obama pledged $90 million to help address the problem during a visit in 2016, the same swing through Southeast Asia during which he sat down at a plastic table for bún cha with Bourdain in Hanoi, Vietnam.

Bourdain was not immune to clichés—when he went to the Congo, you knew you were going to get a healthy dose of Joseph Conrad, likewise some Paul Bowles and William S. Burroughs in Morocco. And as he himself acknowledged in an interview with Slate’s Isaac Chotiner last year, his bad-boy affectations got a little tiresome after a while; the glorification of the sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll hijinks of his early days in the restaurant business contributed to a toxic atmosphere in that industry and was at odds with the cosmopolitanism of his later work.

But at his best, his shows told American viewers, who often see some of the places he traveled to only in the context of war or crisis, that the world didn’t have to be a scary place. The world of Parts Unknown was never kumbaya: Cultural differences were real and sometimes unbridgeable, crises didn’t have easy solutions, but connection over food and conversation was possible. People are more welcoming than you might think. He was also sometimes at his best when turning his camera on his own country, making it clear that a provincial New Yorker can have his mind blown as easily by Houston or Queens as Borneo or Punjab.

I never met Bourdain, though through his investment in the travel website Roads & Kingdoms, he helped support one of my reporting trips. But as a person who’s not naturally outgoing, I also think I might not have had the courage to eat camel meat with my hands in Somaliland, or drink cloyingly sweet wine with a Stalin-loving cab driver in Abkhazia, had I not seen him do far more adventurous things on his shows and come out none the worse for wear with a story to tell. He was an example to anyone who’s ever found themselves in an unfamiliar city where they don’t speak the language and stick out like a sore thumb, and summoned the courage to venture out onto the streets, point at something that looks delicious, and dig in.