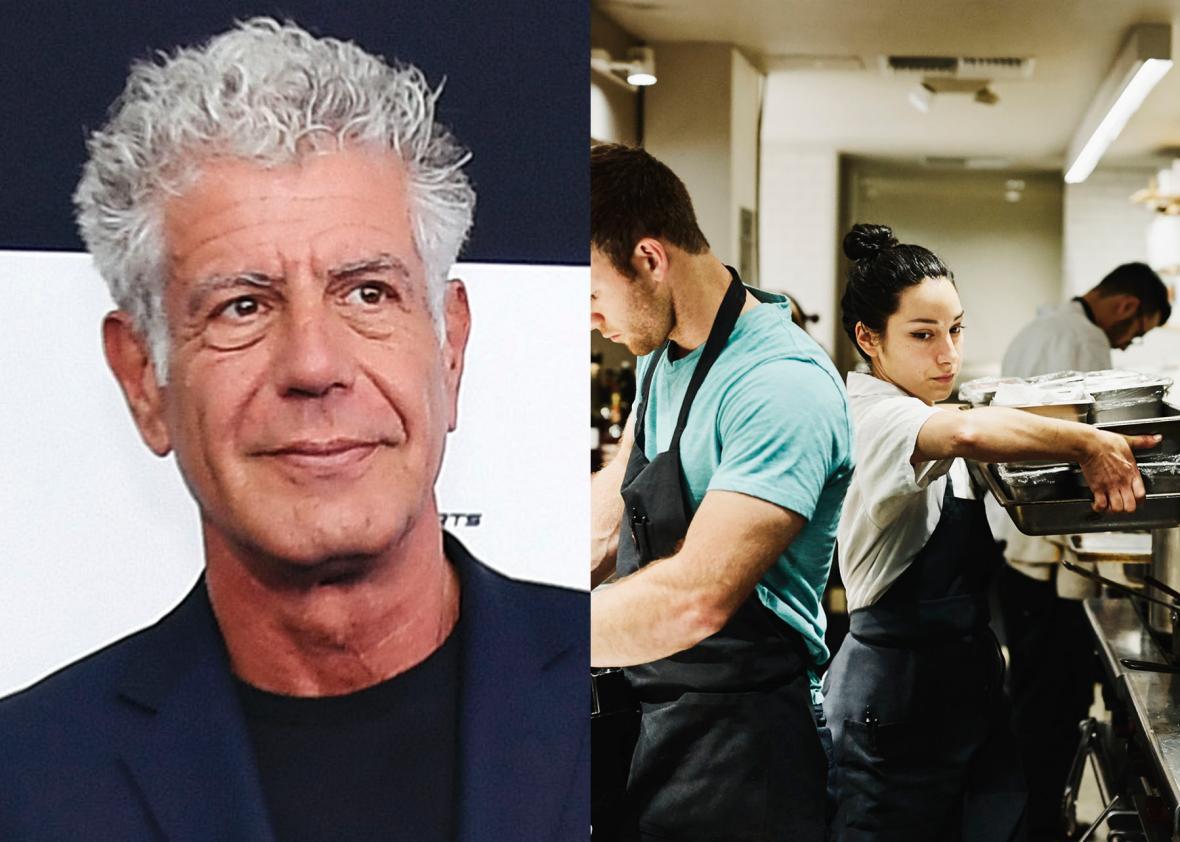

Anthony Bourdain is known as the strutting chef who kicked a drug habit; wrote a best-selling confessional, Kitchen Confidential; and became an internationally recognized television star. But he is also known for his opinionated takes on other chefs, as well as the bad-boy image that his book enshrined in the minds of readers: the fast-talking, foul-mouthed guy who would take on all comers, eat all dishes, and pose with swords on the cover of his book.

Recently, another culinary star, the New Orleans chef John Besh, was forced to step aside from running the group of restaurants he owns after the Times-Picayune reported on allegations that Besh’s company ignored sexual harassment claims and that Besh himself engaged in harassment. Amid this story, and the enfolding Harvey Weinstein saga, Bourdain has taken to Twitter to attack “meathead culture” in the restaurant world and the behavior of men like Weinstein. Bourdain is currently dating Asia Argento, the Italian actress and director who told the New Yorker that Weinstein raped her. Argento recently left Italy after disgraceful treatment by the country’s misogynistic press.

To discuss harassment in the restaurant industry, Weinstein, and his own career, I spoke by phone recently with Bourdain:

Our conversation, edited and condensed for clarity, is below.

Isaac Chotiner: What is it that’s gotten you so passionate about the issues of harassment and assault recently, and specifically what is it about restaurant and food culture that you think needs to change?

Anthony Bourdain: I mean, look, obviously I’ve been seeing up close—due to a personal relationship—the difficulty of speaking out about these things, and the kind of vilification and humiliation and risk and pain and terror that come with speaking out about this kind of thing. That certainly brought it home in a personal way that, to my discredit, it might not have before.

There’s that. And I’m angry and I’ve seen it up close and I’ve been hearing firsthand from a lot of women. Also, I guess I’m looking back on my own life. I’m looking back on my own career and before, and for all these years women did not speak to me.

I’ve been out of the restaurant business for 17, 18 years. I’m really not in the mix. Just the same: Other than one woman chef restauranteur friend from Canada, nobody has really been speaking to me about this until recently. I guess because of the Weinstein case I’m starting to hear personal stories from a lot of women.

What kinds of things are you hearing?

Just personal stories, things that they’ve heard, things that have happened to them. But I had to ask myself, particularly given some things that I’m hearing, and the people I’m hearing them about: Why was I not the sort of person, or why was I not seen as the sort of person, that these women could feel comfortable confiding in? I see this as a personal failing.

I’ve been hearing a lot of really bad shit, frankly, and in many cases it’s like, wow, I’ve known some of these women and I’ve known women who’ve had stories like this for years and they’ve said nothing to me. What is wrong with me? What have I, how have I presented myself in such a way as to not give confidence, or why was I not the sort of person people would see as a natural ally here? So I started looking at that.

And I’ve also been thinking very much about Kitchen Confidential. I would go to signings a few years after Kitchen Confidential came out, and people would come up to me, mostly guys, they’d high-five me over the table with one hand and slide me a packet of cocaine with the other. And it was like dude, have you not read the book? What the fuck is wrong with you?

This is like people coming up to Michael Douglas and saying, “Greed is good,” unironically.

I’ve had to ask myself, and I have been for some time, “To what extent in that book did I provide validation to meatheads?”

If you read the book, there’s a lot of bad language. There’s a lot of sexualization of food. I don’t recall any leeringly or particularly, what’s the word, prurient interest in the book, other than the first scene as a young man watching my chef very happily [have a] consensual encounter with a client. But still, that’s bro culture, that’s meathead culture.

It’s no excuse, but when I arrived in the restaurant business in the early ’70s, it was the waning days of the sexual revolution. It was in Provincetown, Massachusetts, which was a largely gay, very sexually free, libertine-esque environment. I was coming out of a mostly women’s university where men were a tiny minority. I found myself in an environment where men and women spoke—gay men, gay women, straight men, straight women—we all spoke, people were speaking around me, mostly older, more experienced, in an incredibly frank way, usually self-deprecating way, about their sex lives. What they liked, what they didn’t like. How they fucked up. How they’re failures. I found this very liberating and refreshing that people could talk to themselves in this way. Talk to each other in this way.

It seemed honest and free of the kind of hypocrisy and stupidity that I’d seen surrounding sex growing up. But of course, as in any seemingly utopian environment, whether it’s like San Francisco in the ’60s or anyplace else, the meatheads arrive and they see this as a means to be shitheads.

What was it about you that prevented women from coming up and saying, “Hey, this is what happened to me,” or, “This is what’s going on.” What is it, do you think? Do you think it’s something about men and food culture generally, or do you think it’s some aspect of your personality?

Look, I never wanted to be part of bro culture. I was always embarrassed. If I ever found myself, and I mean going way back, with a group of guys and they started leering at women or making, “Hey, look at her. Nice rack,” I was always, I was so uncomfortable. It just felt, it wasn’t an ethical thing; it was that I felt uncomfortable and ashamed to be a man and I felt that everybody involved in this equation was demeaned by the experience. I was demeaned by standing there next to things like this. They were demeaned for behaving like this. It’s like sitting at a table with somebody who’s rude to a waiter. I don’t want to be with someone like that.

But, look, I accepted when the book came out, that I was the bad boy. There I was in the leather jacket and the cigarette and I also happily played that role or went along with it. Shit was good. People said a lot of silly things about me. People actually used the word macho around me. And this was such a mortifying accusation that I didn’t even understand it.

You know, to the extent that I was that guy, however fast and however hard I tried to get away [from] it, the fact is that’s what my persona was. I am a guy on TV who sexualizes food. Who uses bad language. Who thinks our discomfort, our squeamishness, fear and discomfort around matters sexual is funny. I have done stupid offensive shit. And because I was a guy in a guy’s world who had celebrated a system—I was very proud of the fact that I had endured that, that I found myself in this very old, very, frankly, phallocentric, very oppressive system and I was proud of myself for surviving it. And I celebrated that rather enthusiastically.

I mean, I became a leading figure in a very old, very oppressive system so I could hardly blame anyone for looking at me as somebody who’s not going to be particularly sympathetic. They say something to me about someone I know, and maybe I would tell them.

Here is one line from the book: “We’re too busy, and too close, and we spend too much time together as an extended family to care about sex, gender preference, race or national origin.”

But you follow that up by saying conversations with comments like, “Pass the fucking turkey cocksucker,” were common. In such a sexualized environment, is there something naïve about looking at the kitchen that way?

Yes. I just have to cop to that and say yes.

Look, I like to think, I like to think that I never made … Look, there was a period in my life in the kitchen where I was an asshole. I was. I would do the classic, throw plates on the ground. If waiters or waitresses for that matter displeased me I would rail at the heavens, curse, scream. But I like to think I never made anyone feel uncomfortable, creeped out, or coerced, or sexualized in the workplace.

I’ve certainly fired people, even back in the ’80s: If somebody was taking their personal business out on a female employee, or creeping on an employee, they were gone. They were fucking gone. It was just not something I could live with. What was the question?

About saying sex or gender didn’t matter in such a sexualized workplace atmosphere and also—

What made people uncomfortable is something I ask also. At the time was I naïve? Did that level of discourse that was so familiar to me and that so many women were active participants in at the time, you know, the breed of women back then were fucking tough and spoke like sailors. And again, I came out of Vassar, where, my God, I was shocked. I mean it was like being in the locker room with a football team. I was like the only guy at the table and these women were like predators. The exchange of views was sweet and frank and salty but that said, what did I miss? Was I naïve? I’m sure I was. Of course I was.

And from the get-go, this system that I was, let’s be honest, celebrating and bragging about surviving, we’re talking about a militaristic, male system that goes back in Europe back to the guild system, generally populated in the classic example by abused male children who were abused in kitchens, worked their way up through this sadistic system of hazing, became chefs and then abused those below them in the same way. The traditional system was the male chef would abuse his male chef de cuisine. The male chef de cuisine would then abuse his sous-chef. The sous-chefs would take it out on all the cooks who would then physically hit, kick, torment, haze, and pressure each other as punishment for bringing this shit down on them yet again. And God help you if you were a woman in those days.

There are a lot of chefs still walking around who came up through that system. Éric Ripert talked about how he used to be that guy. Then one day he realized, look, I’m miserable and everybody working with me is miserable. This is just not fucking working. And took a hard look at themselves. But the system itself, from the very beginning, was abusive, was male-dominated and cruel beyond imagining.

You knew Besh right?

I’ve met him once. He was on the show for a scene.

Had you heard rumors or anything before all that stuff came out?

No. Again, I’ve been out for 17 years. I’m from New York, he’s in the New Orleans world. I wouldn’t have heard anything because I just don’t move in that world. Even other male chefs, no one would have said anything. Look, I know what I read in the papers and what I read in the papers is a pretty fucking gruesome story.

Were you pissed when a sexually harassing chef character showed up on the Aziz Ansari show, Master of None, and people surmised it was based on you?

No. No, no. Look, I make fun of a lot of people in my career and I think it is entirely appropriate if others make fun of me. I’m friends with Aziz. I haven’t seen it, but I hear it’s very funny. I think I am totally fair game, and I’m completely cool with it. I hear it was great actually.

I just asked because that character was gross, and I wondered if you were pissed about it.

No, no, not at all.

At the beginning of this interview, you mentioned your personal relationship with someone affected by sexual harassment. Has it raised any specific issues about the way we think about these things or complexities that you hadn’t thought through before?

Look, I’ve seen the way Asia has been treated in her home country by the press, and it is disgusting and dismaying and discouraging. You understand why people don’t report these things. When you see what even now, today, what people say. What they would have said on Day One and what they are saying all these years later when women find the strength to be honest. I’ve seen that and I’ve really fucking seen it and of course it makes me angry.

I don’t know the facts of the case or anything with the Besh company, but the fact that it’s a company this size and that there was not a credible avenue, no trustworthy credible office or institution in this big company for women to report or to complain with any confidence that their complaints would be addressed, this is, it’s an indictment of the system.

We saw similar things with Roger Ailes and Fox News.

In that case the whole system is stacked against you, as with Weinstein. You knew that there were would be lawyers. You knew that friendly press outfits like the New York Post would be burying you with slanderous, disparaging information. You knew that you would be blackballed. You knew that you would be mocked. Your career and your business that you worked your whole life for, your entire universe of this field that you love is controlled absolutely by one man and you see his terrible reach and power to crush and silence again and again and again and the willingness of these massive deep pocketed companies to assist in that effort knowingly.

Let’s be fair. Who can stand up to that? Nobody did for 20 years. You just don’t feel like anyone is going to do anything but punish you for telling the truth.

Thanks for chatting.

OK. Hope you can do some good.