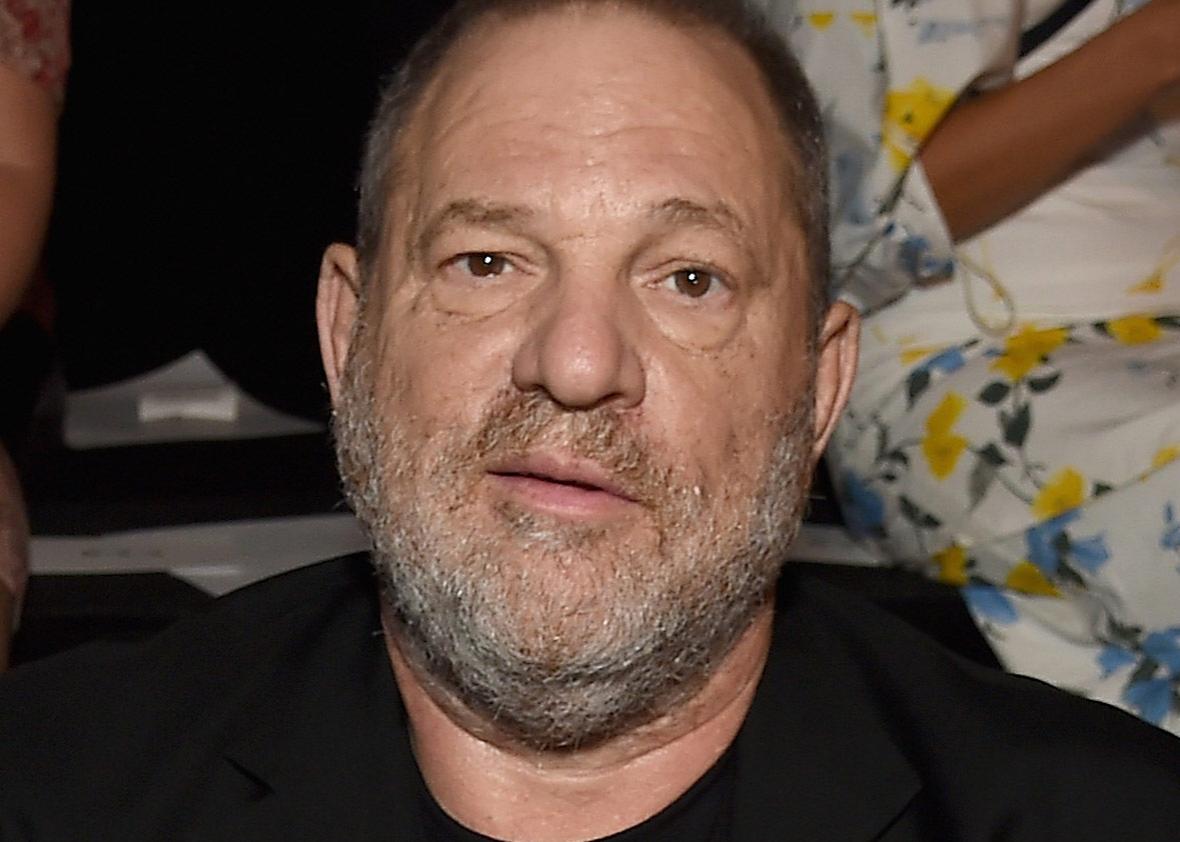

It took two comprehensive and chilling news reports, one from the New York Times and another from the New Yorker, to expose the truth about Harvey Weinstein. Before last Thursday, the film titan’s alleged sexual predations were an open secret to some, a flash in the peripheral vision of others. Now accusations are pouring out from Hollywood stars and aspiring actresses and those who worked for Weinstein’s production company. This is the sound of a decades-long silence broken, of a raft of confidentiality clauses being torn apart.

As Ronan Farrow explained in the New Yorker, “Weinstein and his associates used nondisclosure agreements, monetary payoffs, and legal threats to suppress [his accusers’] myriad stories.” Farrow’s piece quoted one female Weinstein Company employee anonymously, as “her lawyer advised her that she could be exposed to hundreds of thousands of dollars in lawsuits for violating the nondisclosure agreement attached to her employment contract.” The Times reported that Weinstein himself also reached at least eight settlement agreements, with his accusers typically getting between $80,000 and $150,000 in return for their silence. Rose McGowan received a $100,000 payment in 1997, Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey wrote in the Times, “after an episode in a hotel room during the Sundance Film Festival. The $100,000 settlement was ‘not to be construed as an admission’ by Mr. Weinstein, but intended to ‘avoid litigation and buy peace,’ according to the legal document.”

Weinstein succeeded in purchasing “peace” with confidentiality agreements, at least for a time. There is a case to be made that such deals are beneficial to victims. As Vox writes, “a ban on confidentiality clauses in settlement agreements [could] reduce the size of payouts,” as defendants are likely willing to part with more money to settle claims on the sly. But in the case of Weinstein and other powerful alleged abusers, these contracts become yet another tool to exploit those who’ve already been exploited. “It felt like David versus Goliath,” one former employee told the New Yorker about Weinstein’s legal maneuvers in the 1990s. “The guy with all the money and the power flexing his muscle and quashing the allegations and getting rid of them.”

In deciding whether to accept a settlement with a prominent alleged harasser or abuser, women must choose between surrendering their stories (perhaps thereby perpetuating a cycle of abuse) and receiving no compensation for their suffering (and perhaps augmenting that suffering as the abuser retaliates). There is something devastatingly sad about this binary. What’s moral about a pact that predicates receiving justice on stifling your ability to describe the crime?

Literature is loud with ghoulish stories about women whose voices get stolen: Echo helplessly repeating others’ words; the princess Philomela, raped by the king of Thrace, who then cuts out her tongue to ensure her silence. There’s also Hans Christian Andersen’s tale of a sea hag ripping out a mermaid’s voice, an exchange that allows the maiden to walk on land and dance with the prince. This transaction makes the heroine look complicit in her own silencing, even though the power dynamics were always in the villain’s favor.

For men like Weinstein, R. Kelly, Bill O’Reilly, and Bill Cosby—just to name a few of the high-profile figures who’ve profited from nondisclosure agreements—gag orders brush a layer of volition over what is essentially intimidation. They create a self-serving tableau in which victims, rather than simply receiving restitution, are forced to barter for it.

That appearance of cooperation, of a contract that unites two unequal parties against the prying eyes of the world, diminishes the women while absolving the men. In signing a settlement agreement, a victim is coerced into a pose that compromises the public perception of her victimhood even as she cedes control of her narrative to unfriendly hands. It is as if, with their money and influence, Weinstein and his ilk have managed to buy shares in the ownership of reality itself. Meanwhile, the women they target must weigh the value of tending to their own lives against what is to be gained from protecting each other.