Brock Turner earned national fame last summer not for his sexual assault of a passed-out woman behind a dumpster, but for his punishment: six months in county jail, of which he only served three. The internet’s consensus, after reading the victim’s viral statement on BuzzFeed, was that it was far too short a stint for a crime that carried a possible sentence of 14 years in prison.

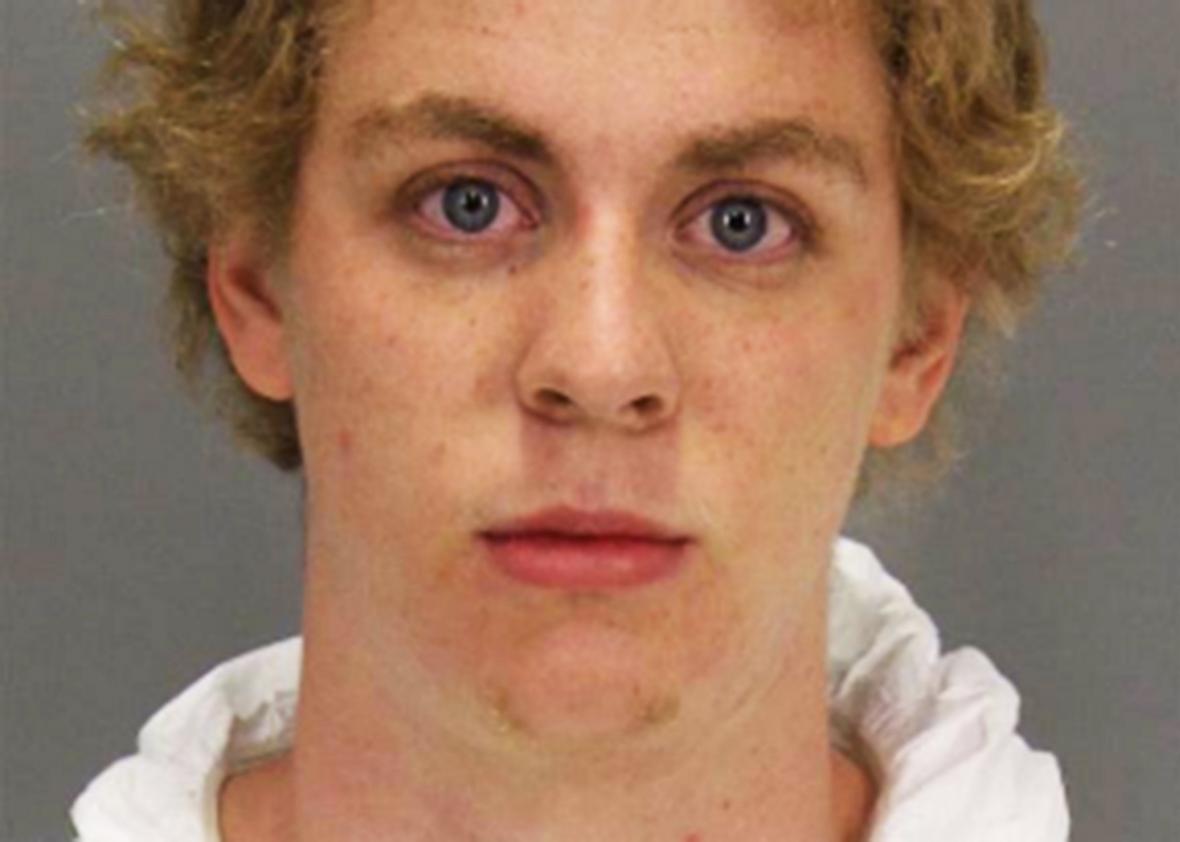

But, though he left jail just over a year ago, Turner’s consequences are far from over. HuffPost reported on Wednesday that the former Stanford swimmer’s mugshot appears next to a section titled “Rape” in the second edition of Introduction to Criminal Justice: Systems, Diversity, and Change, a book used in college-level criminal justice courses. It sounds like a snarky insult come to life: “Your photo should be in the encyclopedia under ‘rapist!’ ” The crime Turner’s father famously characterized as “20 minutes of action” is now immortalized as the literal textbook definition of rape.

This should please those who chastised media outlets that didn’t out-and-out label Turner a “rapist” in coverage of his sentencing. But there was a good reason for careful language in his case: Turner wasn’t convicted of rape. He was convicted of three felonies: assault with intent to commit rape of an intoxicated person, sexually penetrating an intoxicated person with a foreign object, and sexually penetrating an unconscious person with a foreign object. In California, a charge of rape requires forcible sexual intercourse, which Turner did not commit.

Putting Turner’s photo next to the heading “Rape,” then, is more than a little misleading in an introductory textbook that should help students differentiate between crimes that are similar but not identical. The description under the heading also identifies the photo as “rapist Brock Turner”—an inaccurate characterization of Turner’s crimes. Under the FBI definition of rape proffered in the book, the crime does include penetration with a foreign object. But under the penal code of California, where Turner was charged, his crime was not rape, and he is not a “rapist.” It wasn’t the particulars of his assault that made him a newsworthy sexual assailant. It was the response to the crime, both from the judge in his case and from the general public.

But to its credit, the textbook does seem to want to present Turner as a case study through which to examine the subjectivity of the justice system. “Some are shocked at how short [Turner’s] sentence is,” the book reads. “Others who are more familiar with the way sexual violence has been handled in the criminal justice system are shocked that he was found guilty and served time at all. What do you think?”

With her heartwrenching statement, the victim in Turner’s case changed the way many people viewed sexual assault. She opened the door for difficult discussions about theories of fair sentencing, including the idea that a permanent spot on a sex offender registry is too harsh a punishment for Turner, or for anyone else—theories that students should absolutely dissect in criminal justice classrooms. If Turner hadn’t become one of most famous noncelebrity sexual assailants of all time, for better or worse, the textbook authors might have chosen another lesser-known figure to illustrate the topic or left the concept in the realm of theory. With the public discourse Turner’s victim began, at least the authors were able to use a familiar case to bring a vivid urgency to both a terrible crime and our inadequate system for punishing it.