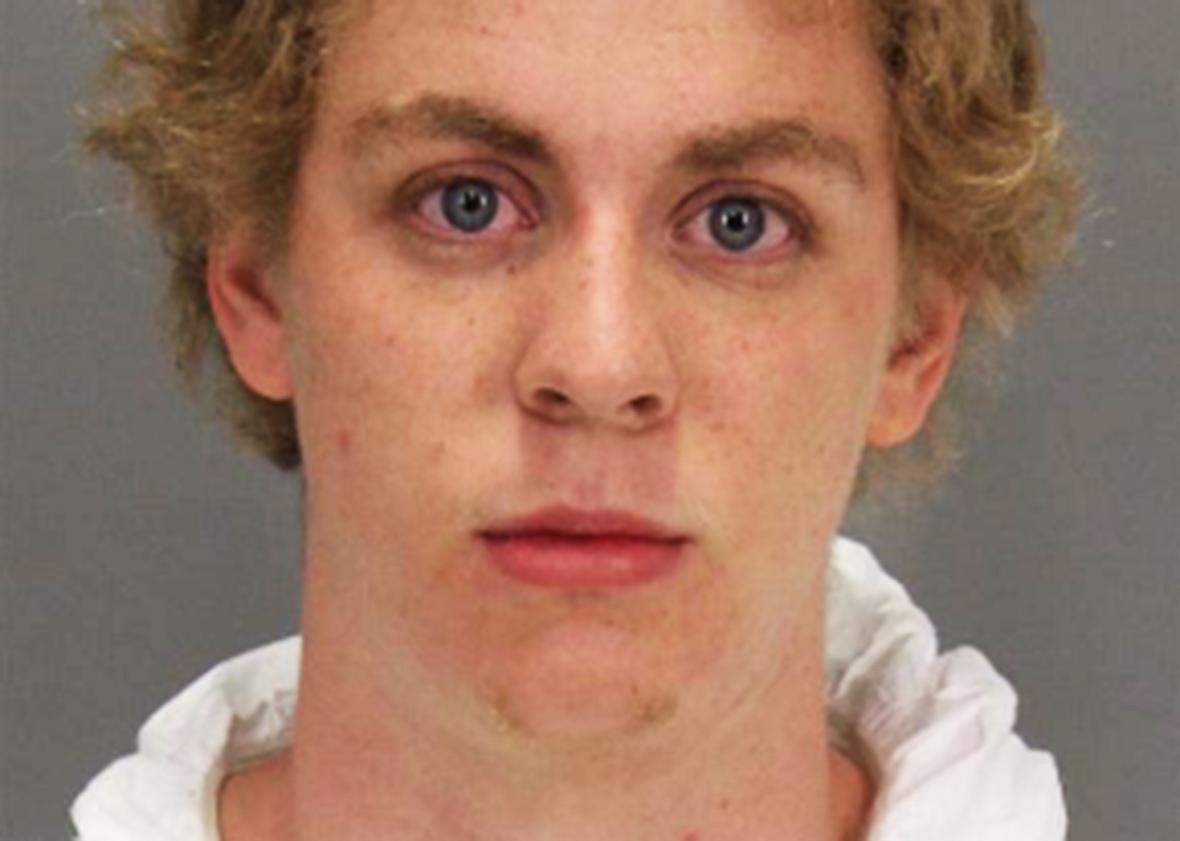

Six months in county jail, maybe less with good behavior. That’s the punishment Santa Clara County Superior Court Judge Aaron Persky saw fit for Brock Turner’s crime of sexually assaulting an unconscious woman behind a dumpster outside a Stanford frat party. Turner, 19 at the time of the assault, was found guilty of three counts of felony sexual assault and was eligible to face 14 years in state prison; county prosecutors had asked for six years.

Turner’s victim wrote a devastating statement arguing that the sentence was too lenient; in a letter that perfectly exemplified the rape culture that enabled the light sentence, Turner’s father requested no jail time at all. Persky decided six months was enough—any more than that, he said, would have a “severe impact” on Turner.

Of course, when it comes to criminal punishment for sexual assault, imposing a severe impact should be the point. A short stint in jail will be a blip in the lifetime of a 20-year-old man. The more severe impact will come later, when Turner leaves jail and becomes a lifetime member of the sex offender registry.

Punishments for sex offenses are levied for three interconnected purposes: protecting a community from harm, sending a message to potential criminals about the consequences that await them, and rehabilitating offenders. Sex offender registries are databases of people who’ve commit sex-related crimes, which can range from public urination and indecent exposure to child pornography possession and rape. They are often publicly searchable and, depending on the state, can prevent registrants from living within certain distances of schools, churches, malls, parks, or airports; bar them from certain jobs; and require them to notify their neighbors that they once committed a sex crime. Registrants must also keep law enforcement apprised of any change in address, school, or employer; homeless sex offenders in Kansas have to report to law enforcement every three days. These registries serve no rehabilitative function—they are primarily meant to keep likely offenders from potential victims and help law enforcement identify recidivists. In the ’90s, through legislation like Megan’s Law, sex-offender registries were made public as a way for communities to know if, say, a serial child molester out on parole had moved in down the street.

Now, many who once championed the registries—including Patty Wetterling, whose son’s abduction spurred the first federal mandate for each state to form a registry—have begun to question how they’ve morphed into tools that cause more harm than good. “I think they were started with a logical idea that if you have a list of people that have committed a sex crime, you’re probably at a good place to find out who might have committed a new sex crime,” Josh Gravens, a 29-year-old activist who was placed on a sex offender registry after touching his younger sister inappropriately when he was 12, told Slate. “To be honest, I don’t know why we have them today, because research would say they’re useless and ineffective and have devastating collateral consequences for more than just the people listed on them.”

Those consequences, which include homelessness, poverty, and unemployment, are not matched by attendant benefits to society. Sex offender registries have not caused any measurable decrease in sex crimes. Supporters of sex offender registries often base their arguments in the rhetoric of protecting children from pedophiles; that’s why laws prohibit registrants from living within certain distances of schools or frequenting malls. But more than 90 percent of child abuse cases arise within the family at home, not in public places where a stranger might snatch a kid.

“We as a society are quite uncomfortable with acknowledging we have a huge problem” with sexual assault and sexual abuse, Gravens says, “and it’s not just coming from people on a list. It’s a lot easier for us to play dumb and have our safety blanket that is the registry.”

Turner was not on any list, yet he committed sexual assault. He did not molest a child, yet he will now be barred from housing near schools and playgrounds. If he feels unjustly persecuted now, as he and his defenders have blamed his assault on a culture of binge drinking and promiscuity, a lifetime on the sex offender registry will do little to change that. “Is it helpful for him to be on a registry? I don’t think so,” Gravens says. “It has not proven to be an effective tool for stopping the very crime for which he’s placed on it.”

Once Turner finishes his jail sentence, no registry could prevent him from going to a party, taking an intoxicated woman behind a dumpster, and sexually assaulting her. But studies show that young sex offenders are good candidates for rehabilitation programs. Their brains are not fully developed until their mid-20s, so they usually don’t fully recognize the potential consequences of their actions, unlike older offenders. “Most teenagers, and by most I mean 95 percent, don’t reoffend sexually once they’re caught,” Elizabeth Letourneau, director of the Moore Center for the Prevention of Child Sexual Abuse, told then–Salon reporter Irin Carmon in the wake of the famous 2013 rape case in Steubenville, Ohio. “Being caught has an important deterrent effect.”

There’s a strong case to be made against the social value of most prison sentences—people who’ve been incarcerated face lifelong barriers to recovery and reintegration into society—but the fact remains that Turner’s sentence is far lower than what most perpetrators incur for similar crimes. He was convicted of three felonies, each of which could have carried at least a year of prison time. According to a Bureau of Justice Statistics report, in 1997, the average sexual assault prison sentence was 6½ years, with three years served. At the time, the average sentence had stayed stable for nearly two decades, while time served was growing. In Turner’s case, the probation officer and judge took into account the fact that he had lost a swimming scholarship at a prestigious university and counted that in his favor—a clear example of how Turner’s privilege granted him clemency where others would have found rigid law and order. Judges have broad autonomy when it comes to sentencing, paving the way for them to sentence black federal offenders to prison times an average of 10 percent longer than white offenders with similar arrest records and crimes.

In her statement, Brock’s victim made clear that she did not want Brock “to rot away in prison” but wrote that “the probation officer’s recommendation of a year or less in county jail”—less than the state’s proffered minimum sentence—“is a soft timeout, a mockery of the seriousness of his assaults, an insult to me and all women.” Her vision of an appropriate way forward, rooted in an apology from Turner and a true understanding of what he did wrong, suggests the school of restorative justice, which centers victims and would rather offenders work to redress their wrongs than endure punishment for the sake of punishment.

But in this case, the victim did not seem to take issue with Turner’s mandatory sex offender registry. “He is a lifetime sex registrant. That doesn’t expire,” she wrote. “Just like what he did to me doesn’t expire, doesn’t just go away after a set number of years.” Even setting aside the fact that sex offender registries were never originally intended as retributive, Emily Horowitz, author of Protecting Our Kids? How Sex Offender Laws Are Failing Us, doesn’t think it makes sense to consign anyone to that fate for life. “The sex offender registry is punishment on steroids,” she told me. “Does the registry make anyone safer? Not according to any research. Are sex offenders destined to reoffend? Not according to any research—sex offenders have lower recidivism rates than almost any other type of offender. Punishing [Turner] forever and destroying his life doesn’t make anyone safer.”

How, then, can we make our communities safer? Although sex offenders are statistically unlikely to reoffend, registries can actually impair any kind of rehabilitation by isolating offenders from their communities and ensuring that they have little to lose if they commit another crime. In Western Australia, the Department of Corrective Services runs a series of rehabilitation programs: Through group therapy, one-on-one therapy, and written homework, sex offenders learn to recognize triggers, avoid certain “high-risk” situations, manage their anger, and associate “deviant” thoughts with memories of the negative consequences of associated actions. They discuss how their actions have harmed their victims, confront deeply held views on women and gender, and dissect how they’ve justified their own behaviors to themselves. Participants are taught to approach their treatment as tools for control, not a cure; sex offenders who believe they’re cured risk becoming complacent and relapsing, as a substance abuser might.

The way adult role models frame sexual assaults and their penalties also has a strong influence on young people. In his letter, Turner’s father delivered a strong statement to Turner, his peers, and other young men and women that what Turner did was no big deal—just “20 minutes of action”—and that the victim ruined his life by taking him to court for it. By spending a year blaming the victim and rationalizing Turner’s actions rather than encouraging their son to take responsibility for his crime, Turner’s parents have made their community a little less hostile toward sexual assault and a little more threatening toward victims deciding whether to press charges against their rapists. By defending their son to the very end, they have almost certainly affected his likelihood of raping again once his few months in jail are up. After Steubenville, Amy Davidson wrote in the New Yorker that the recurring narrative of a young man’s life being ruined by a sexual assault conviction completely misses the point:

Telling those teen-agers that there shouldn’t have been consequences might mean another victim, in another town, years in the future. It also affects what sort of men the boys become, and one has to think that [convicted rapists Ma’lik Richmond and Trent Mays], too, have an interest in that. Does it destroy a teen-ager’s life to take him off the path of being an adult rapist? Perhaps it is too abstractly (even annoyingly) philosophical to ask what the “better” life is—one in which you have a remote shot at being in the NFL, or one in which you might be a person who treats others decently?

Multiple studies have shown rehabilitation programs to be particularly successful with juvenile sex offenders. This raises the very likely possibility that sex offenses perpetrated by adolescents could be prevented with early intervention and behavior-modification training in schools. To do that, lawmakers and community leaders would have to put power and money behind their repeated claims of utmost concern for victims. Sex offender registries offer a strong-sounding gut response for many who are disgusted and frightened by the crimes our neighbors are capable of committing. But all the lists and housing restrictions and enforced unemployment in the world won’t stop a person with a sense of entitlement and a screwed-up view of women from raping someone behind a dumpster. Prevention will always be preferable to punishment, but it’s harder to sell an upfront investment without the visceral tingle of retribution.