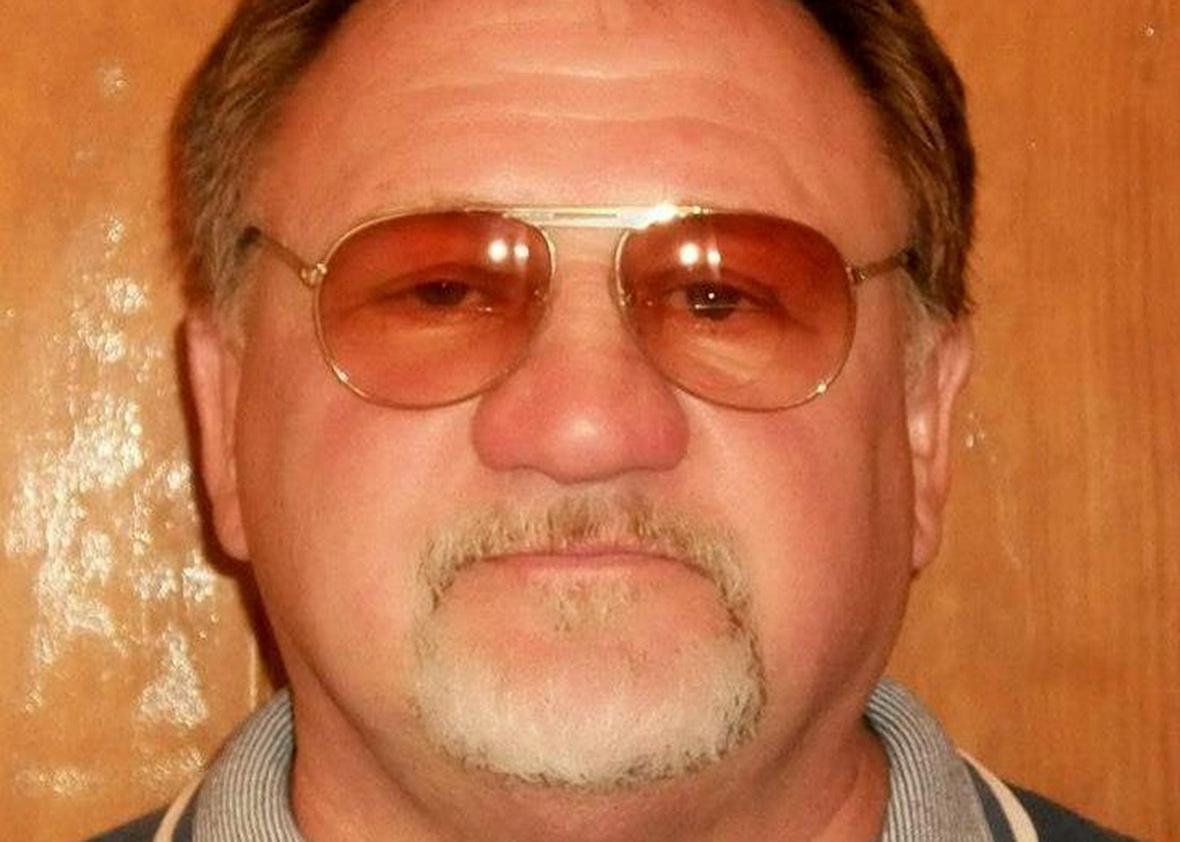

Americans who follow news about public shootings in the country will not be surprised by the biography of James T. Hodgkinson, the 66-year-old from Belleville, Illinois, who shot up a D.C.-area baseball practice for congressional staffers on Wednesday morning.* He is a white man with a legal license to own firearms, for one thing. And, like so many men who attempt mass murder, he has a history of violence against women.

On Wednesday, Hodgkinson shot two Capitol Police officers, House Majority Whip Steve Scalise, and multiple congressional staffers, all of whom have survived their injuries. (Hodgkinson was killed by law enforcement officers.) According to police records, he had committed violent acts before. In April 2006, Hodgkinson was arrested in Illinois after allegedly punching a woman in the face at a private residence and firing a shotgun at a young man at the scene. NBC reports that police recovered a shotgun, a pocket knife, and hair from a woman’s head at the scene; the Daily Beast is reporting that Hodgkinson was seen “throwing” another woman identified as his daughter around a room, hitting her, pulling her hair, and grabbing at her. The first woman tried to leave in a car with Hodgkinson’s daughter, but he reached in, turned off the engine, and cut her seatbelt with a knife. Though Hodgkinson was charged with battery, his case was later dismissed.

The relationship among the three victims of Hodgkinson’s attack is somewhat unclear, but all were lucky to escape. Domestic assaults are 12 times more likely to end in murder when a gun is involved, and the simple existence of a gun in a home makes it five times more likely that an incident of domestic violence will end in a murder. Last year, a large analysis of gun data across the country found that high rates of gun ownership in a state correlated with high rates of homicides, and women are disproportionately victimized by that rise in murder rates. After controlling for demographic differences, researchers found that gun-ownership rates caused just 1.5 percent of the rise in murders of men but 41 percent of the rise in murders of women. The more gun owners a state has, the more likely a woman is to be killed by someone she knows—a fact that negates the right-wing mantra that women need guns to protect themselves from killers.

By now, news consumers are used to hearing in the wake of a public shooting that the perpetrator has been charged with domestic abuse or committed violence against women before. The shootings at the Fort Lauderdale airport; Virginia Tech; Isla Vista, California; Orlando’s Pulse nightclub; and San Bernardino—all were committed by men who had histories of abusing women. It would be more accurate to assume that any random mass shooter is a domestic abuser than to assume he’s not: The average mass shooter in America, defined as someone whose attack killed four people not including himself, has committed domestic abuse. A recent Everytown for Gun Safety analysis of crime records between 2009 and 2016 found that 54 percent of U.S. mass shootings in that time period involved the murder of a family member or intimate partner.

Hodgkinson wounded several people in his attack but killed no one, so he doesn’t qualify as a mass shooter under Everytown’s standards. Wednesday’s shooting wasn’t targeted at a partner or family member, either. This highlights the depth and scope of the connection between domestic abuse and public violence: Hodgkinson and people like him don’t even figure into these chilling statistics. In a great number of the shootings Everytown studied, domestic abusers killed bystanders and friends in addition to the targets of their abuse. Domestic violence is not a personal problem or an attack against a single individual. It betrays an attacker’s perverted relationship to power and should be treated with severity befitting of what it is: a warning sign and predictor of future acts of mass violence.

That is not how U.S. laws treat domestic abusers today. Though federal law prohibits convicted domestic abusers from purchasing guns, there are several cavernous loopholes that benefit abusers and put the rest of us at risk. If an abuser is his victim’s intimate partner but not legal spouse, cohabitant, or co-parent, the law doesn’t apply. In most states, abusers can keep the firearms they already have, making the ban moot for gun owners. And convicted perpetrators of domestic violence, like all people with criminal records, can avail themselves of a wealth of options for gun procurement without having to undergo background checks. Conservative judges and justices are still defending domestic abusers’ rights to own guns.

When they do, they’re protecting men like Esteban Santiago, who allegedly tried to strangle his girlfriend multiple times before he was charged with the murder of five strangers in an airport, and Hodgkinson, who was never convicted on battery charges but whose history of violence against women might have warned of a future violent attack. The price for their freedom to own the most efficient weapons mankind has ever devised is nothing short of public safety and women’s lives.

*Correction, June 14, 2017: Due to an editing error, this post originally misstated the date of the congressional baseball shooting. It was Wednesday morning, not Tuesday morning.