So I’ve heard Pope Francis is coming to the U.S. this week. Anything else going on?

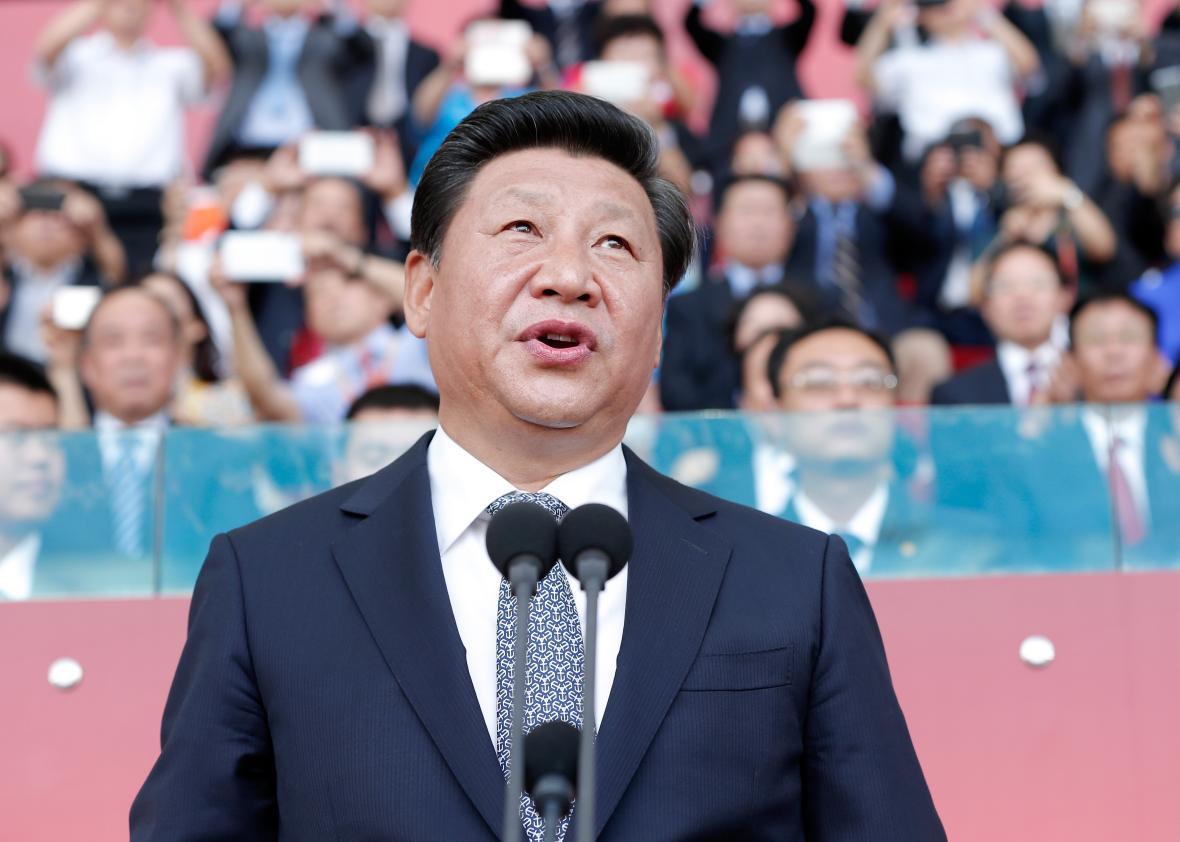

Well, there’s Xi Jinping. He’s the president of China, the world’s most populous country and second largest economy, which also happens to be the largest holder of U.S. debt, second largest trading partner, and a potential military rival. He’s also coming.

Seriously? Can’t they space these things out?

Well the U.N. General Assembly is happening so all the world leaders are coming over anyway.

Fine. So what’s he doing here?

On Tuesday, he touches down in Seattle, where he’ll tour Boeing, schmooze with Henry Kissinger, have dinner with Bill Gates, and give a policy speech. Then, on Thursday, it’s off to D.C. where he’ll meet with President Obama and attend a State Dinner on Wednesday night. Next Monday, he’ll be addressing the U.N. General Assembly in New York.

Sounds like a fun trip!

Not exactly. Xi’s visit comes at an interesting and uncertain time for China. Twenty-five years of breakneck economic growth have pulled millions out of poverty, catapulted the country to superpower status, and defied critics who predicted that the ruling Communist Party’s authoritarian political system couldn’t coexist with capitalism. But China’s economic miracle is slowing down as its population ages and its export-led economic model brings diminishing returns. The government’s jittery and seemingly ad hoc responses to recent market fluctuations have suggested that China’s leaders might not be the ultra-competent stewards of the country’s economic rise that we all thought they were.

So how screwed is the Chinese economy?

Hard to say, in part because no one is quite sure whether to believe China’s official numbers, but growth is almost certainly slowing and that could have an impact on every country that does business with China, i.e. basically every country. Emerging market economies that sell the raw materials that have fueled China’s meteoric growth are particularly vulnerable, and some forecasters are worried China could tip the world back into recession.

But Donald Trump says China is beating us on trade. What’s he talking about?

It’s valid to say that China hasn’t always played quite fair on trade, but a lot of the talking points you’ll hear on the campaign trail are a little out of date. Here’s what’s really happening: Most major economies allow the value of their currencies to float based on market forces, but China’s central bank still sets the value of its currency, the yuan, every morning. For years, the U.S. has accused China of keeping the yuan artificially low. This drives down the price of Chinese goods, boosting the country’s exports to the detriment of manufacturers elsewhere. China—which has been pushing for the yuan to be accepted as a global reserve currency like the dollar, euro, pound and a few others—had recently been keeping the yuan mostly stable, but then surprised everyone last month by devaluing it sharply without warning. . While the country’s central bank says it will now let the market play a greater role in determining the yuan’s value, as international financial institutions and foreign governments have been demanding, people in Washington were still pretty upset. For one thing, China’s devaluation prompted other countries to devalue their own currencies, sparking fears of a race to the bottom. Some in Congress are now pushing to get language addressing currency manipulation added to upcoming trade agreements. Still, China’s recent moves look a lot less like cheating than a panicked response to an impending slump.

Hmm, OK. So Xi’s visit is mostly going to be about the economy.

Oh, no, that’s just one thing.

Really? What else is going on?

Take your pick: Competition in South China Sea, the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade deal, investment, Japan’s new military posture, North Korea, counterterrorism, the Iran nuclear deal, cyberespionage, regular espionage, the new Chinese-founded competitor to the World Bank, intellectual property, energy markets, human rights, Tibet, freedom of religion, immigration, and preventing two different scenarios—catastrophic climate change and nuclear war—that could destroy human civilization as we know it.

Too much! Just tell me what’s likely to come up on this trip.

You’re likely to hear a lot about hacking and the South China Sea. The U.S. has accused the Chinese government and military of being involved in a plethora of hacks against American corporate and government interests. The U.S. has been largely frustrated in its attempts to prevent these attacks or hold China accountable for them. China has also been raising eyebrows with its activities in the South China Sea. The Chinese government argues that it has a historical claim to nearly the entire sea, and has been building up a series of artificial islands to bolster those claims. This has enraged countries in Southeast Asia, who have their own claims in the area, and alarmed leaders in Washington, who worry that China could impede freedom of navigation in the region and that the islands would give it a strategic advantage should armed conflict break out.

What is the U.S. doing to confront China about all this?

Not much, and that has a lot to do with the trip itself. The U.S. has vowed to retaliate for cyberspying by slapping sanctions on Chinese companies and individuals believed to have profited from it, but reached an agreement with Chinese officials to hold off until after the trip so as not to overshadow the event. Similarly, U.S. military officials want to test China’s claims in the South China Sea by sending ships or planes into the disputed areas, but the White House has held off so far, hoping for a diplomatic resolution.

Has China done anything to help ease tensions ahead of this visit?

They released one prominent dissident and the pace of cyberattacks seems to have slowed.

That’s nice.

They also just arrested a U.S. citizen for spying.

Oh, that’s less nice. Why would they do that now?

Could be retaliation for recent U.S. charges against Chinese individuals for spying, or a move to increase China’s leverage in talks over cyberspying. It could also just be a coincidence, but that would be odd given how hard everyone’s been trying not to let anything overshadow this trip.

Tell me more about this Xi guy. What kind of leader is he?

He’s been called China’s “most authoritarian leader since Mao.” He’s also probably the most individually powerful. His signature initiative has been a massive anti-corruption purge that has targeted tens of thousands of officials ranging from local functionaries to some of the most powerful people in the country, with sentences ranging from small fines to the death penalty. This may have been partly motivated by legitimate concerns over official corruption, but it has also had the convenient side benefit of sidelining most of Xi’s political rivals. At the same time, Xi has presided over an intensified crackdown on political dissent, particularly online.

So people hate him?

Actually, he remains extremely popular at home—particularly for his fight against corruption. Even with the crackdowns, he’s cultivated a more relaxed and human image than his stiff predecessors and has developed a bit of a personality cult, reversing decades of the Communist Party’s attempt to compensate for the excesses of the Mao era by downplaying attention on individual leaders.

What’s his background?

Xi plays down his origins, but they’re fascinating. Decades before Xi launched his own party purge, his childhood was defined by one. His father, Xi Zhongxun, was an early Communist Party member, guerilla commander, and one of Mao Zedong’s top lieutenants. After the revolution, he rose to the rank of deputy prime minister, but in 1962 was purged from the party and imprisoned in a labor camp for 16 years for publishing a book deemed critical of Mao. During that time, his family, including the younger Xi, were sent to a small village in northwest China where they lived in poverty. The elder Xi was later rehabilitated, rejoined the government, and helped implement the country’s early economic reforms in the 1980s. Liberal by Chinese government standards, he is believed to have been disgusted by the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown though he said nothing about it publicly.

Interesting! What about his family now?

Until a few years ago, first lady Peng Liyuan, who will accompany Xi to the U.S. this week, was a lot more famous than her husband. The “peony fairy,” as she is known, is a famous folk singer and regular on Chinese television who also happens to be a major-general in the People’s Liberation Army. (Photos of her singing to troops following the 1989 Tiananmen massacre have been heavily censored in China.) In contrast to previous Chinese leaders’ wives, who have tended to fade into the background, Peng has taken on more of a U.S.-style first lady role. She appears frequently in public and has become a bit of a fashion icon. She and Michelle Obama will probably both be very stylish at the State Dinner.

Do they have kids?

Yep. Their daughter, Xi Mingze, attended Harvard under an assumed name and kept an extremely low profile on campus.

Is Xi corrupt?

Not personally, as far as we know, but foreign media outlets have reported on the private fortunes of some of his relatives and promptly found themselves blocked in China.

So what are Xi’s big plans for China?

Even if you don’t buy, as some prominent China-watchers are now arguing, that the Communist Party is at risk of collapse, Xi has his work cut out for him. The big hurdle is to transition China’s economy from the labor-intensive, heavy manufacturing export model that it has been relying on to a model based more on innovation, technology, and providing services for the country’s growing middle class. To do that, Xi’s going to have to fight some pretty powerful entrenched interests. The negative consequences of unfettered growth are also becoming clear, not just in the smoggy skies over Chinese cities and polluted soil and water, but in horrifying disasters like August’s massive explosion at a chemical plant in Tianjin. Xi has said the right things about cleaner, safer, more sustainable economic development, but it’s not going to be easy to implement. The recent economic troubles will also make it tempting to double down on the state-led investments in heavy industry that have served the country’s needs well until now. Meanwhile, the country’s population growth is stalling, even as it eases up on the infamous one-child policy.

Will he keep cracking down on his opponents?

Politically, the Communist Party under Xi seems to have little interest in opening up the system to more dissent, but restrictions, particularly on the internet, can make life difficult for the kind of innovative entrepreneurs that Beijing hopes will transform the country’s economy. So: We’ll see.

Can we expect any big breakthroughs on this trip?

It’s certainly possible. The landmark 2014 emissions deal between China and the U.S. was announced without much warning while Obama was in Beijing. But things have gotten a bit tenser since then, and for now, both sides would probably settle for getting through the week without a major diplomatic incident.