On Wednesday, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit heard arguments in Hively v. Ivy Tech Community College, a critical gay rights case that could wind up at the Supreme Court. Hively involves Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibits employment discrimination “because of sex.” Some federal courts, as well as the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, have found that sex discrimination encompasses sexual orientation discrimination—and that anti-gay workplace discrimination is thus already illegal nationwide. Wednesday marked the EEOC’s first opportunity to test this interpretation in a federal appeals court since it adopted the theory in 2015.

The 7th Circuit is currently dominated by Republican appointees. But its conservatives are famously astute and open-minded, and by the end of oral arguments, it seemed clear that a majority of the court would rule that Title VII bars sexual orientation discrimination. This consensus developed right around the time that John Robert Maley approached the lectern to defend Ivy Tech’s right to discriminate against gay employees. The ensuing colloquies were at once slightly painful and extremely amusing, as the top legal minds in the country excoriated Maley’s sophistry and revealed the flimsy intellectual foundation of his arguments. Below are five of the most entertaining exchanges of the morning. (Note: Try visiting this link if you are unable to see any audio players.)

Judge Frank Easterbrook is a Ronald Reagan appointee with deeply conservative instincts—but those instincts seem to have pointed him toward an enlightened view of the case. Easterbrook asks Maley to address the EEOC’s analogy to Loving v. Virginia, in which the Supreme Court struck down anti-miscegenation laws. Those laws, the court declared, constituted unlawful race-based discrimination, because they punished individuals who associated romantically with people of another race. By “exactly the reasoning of Loving,” Easterbrook says, anti-gay discrimination can be viewed as illegal sex discrimination, because it punishes an individual for associating romantically with a person of the same sex.

The more Maley struggles to rebut Easterbrook’s Loving question, the more irritated Easterbrook grows. Maley’s tergiversations leave Easterbrook exasperated: “I would appreciate it if you would address the significance of that case,” he growls. Chief Judge Diane Wood then jumps in: “You can’t just stand there and say [Loving] is ‘different’ ” without explaining why, she tells Maley. But he did not explain why; apparently, he simply cannot.

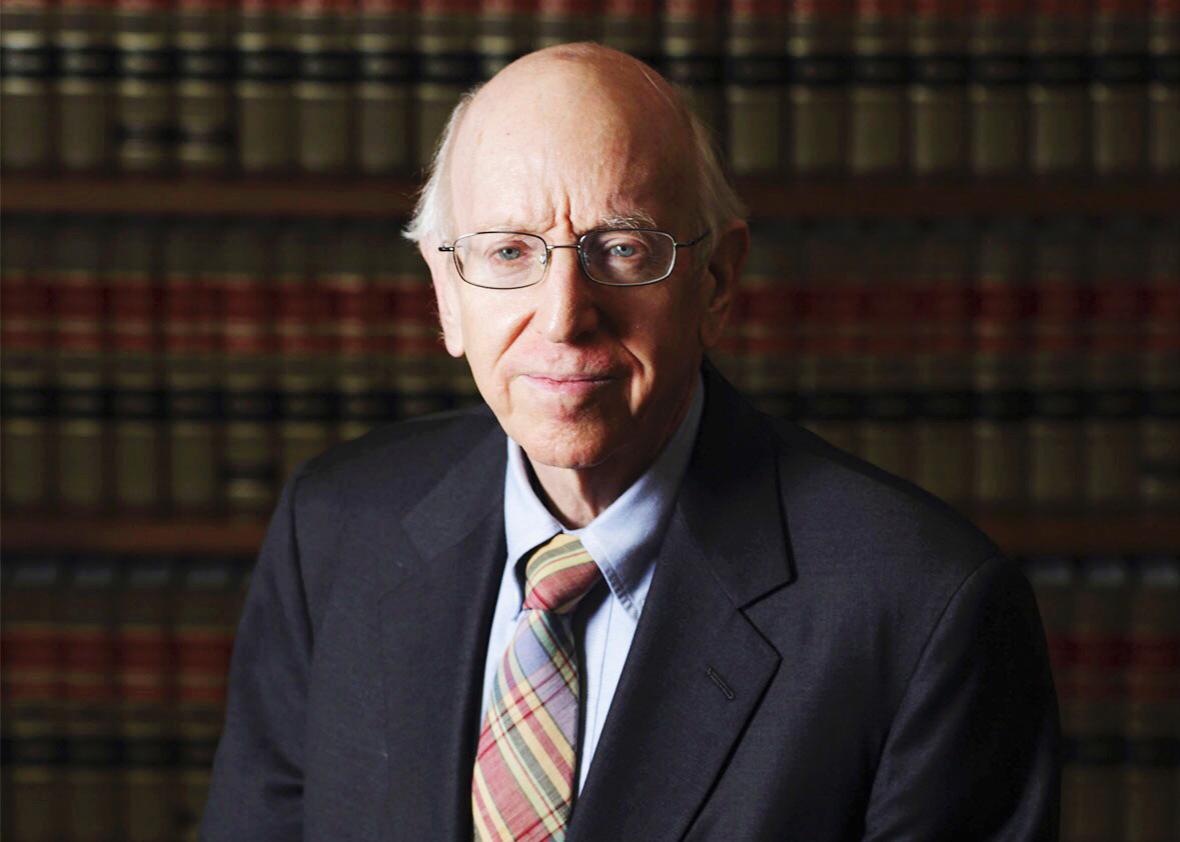

Judge Richard Posner despises the ostentatious formalism that has come to dominate statutory interpretation, thanks in large part to the work of his intellectual nemesis, the late Justice Antonin Scalia. Hively gave Posner an opportunity to bash Maley’s highly formalistic argument that because Congress did not intend to protects gays when it passed Title VII in 1964, the law must not protect gays today. “You seem to think that the meaning of the statute … is frozen on the date of enactment,” Posner says. “Is that your position? Because, of course, that’s false.”

Posner’s tutorial on statutory interpretation is a lot of fun—but oddly enough, Title VII is one area in which Scalia’s formalism pushed him in a surprisingly progressive direction. In a 1998 decision called Oncale v. Sundowner, Scalia wrote that Title VII prohibited male-on-male sexual harassment, even though the Congress that passed the law likely had no intent to outlaw such behavior. “Statutory prohibitions often go beyond the principal evil to cover reasonably comparable evils,” Scalia wrote, “and it is ultimately the provisions of our laws rather than the principal concerns of our legislators by which we are governed.” The EEOC cites this passage as proof that Title VII may cover sexual orientation discrimination by its plain meaning, regardless of Congress’ intent.

Posner can’t resist one more dig at Scalia—this time, a highly topical one. Just a day after President-elect Donald Trump tweeted that flag-burning should be punished with imprisonment or expatriation, Posner referenced Texas v. Johnson, a Supreme Court decision in which Scalia cast the fifth vote to hold that the First Amendment protects flag-burning. Scalia’s vote in Johnson was admirable but arguably inconsistent with his position that the Constitution must be interpreted in accordance with the original meaning of its words.

“When Justice Scalia voted to classify burning the American flag in a political demonstration as a form of speech,” Posner asks, his voice dripping with sarcasm, “do you think he was simply going back to what 18th-century people thought when they said ‘free speech’ and the First Amendment?” Posner scoffs. “Oh, free speech, yeah, burn things, sure that’s a form of speech, right?”

Ivy Tech has an internal policy that prohibits discrimination against gay employees. Yet it argues in court that it is perfectly legal for the school to discriminate against gay employees. This inconsistency perturbs Wood, who scolds Maley for defending Ivy Tech’s hypocrisy. “It is a little odd,” she says. “You said, ‘we deplore sexual orientation discrimination—but we’re going to defend our right to do it anyway.’ ”

The strangest question of the day came, of course, from Posner, who asked Maley, “Why do you think there are lesbians?” His point, it seems, is that homosexuality is immutable and biological, meaning that, genetically speaking, sex includes sexual orientation. But his line of questioning is temporarily derailed by the 90-year-old Judge William Joseph Bauer, who quips, “It’s not just ugly men, huh?”

In the end, poor Maley made the best of a bad situation, maintaining his dignity over the course of 30 cringe-worthy minutes while holding a losing hand. If the Supreme Court eventually takes this case, Ivy Tech will likely find more polished defenders of its seemingly indefensible position. For now, however, we can all enjoy the fact that an esteemed federal appeals court spent a morning debating why lesbians exist and whether they have rights—and appeared to reach a humane, logical conclusion.