One of the bewildering things about Hurricane Harvey, for observers and especially for Houstonians themselves, has been the lack of a comprehensive sense of the extent of the flooding. We don’t quite know, quite yet, who has been hit the worst.

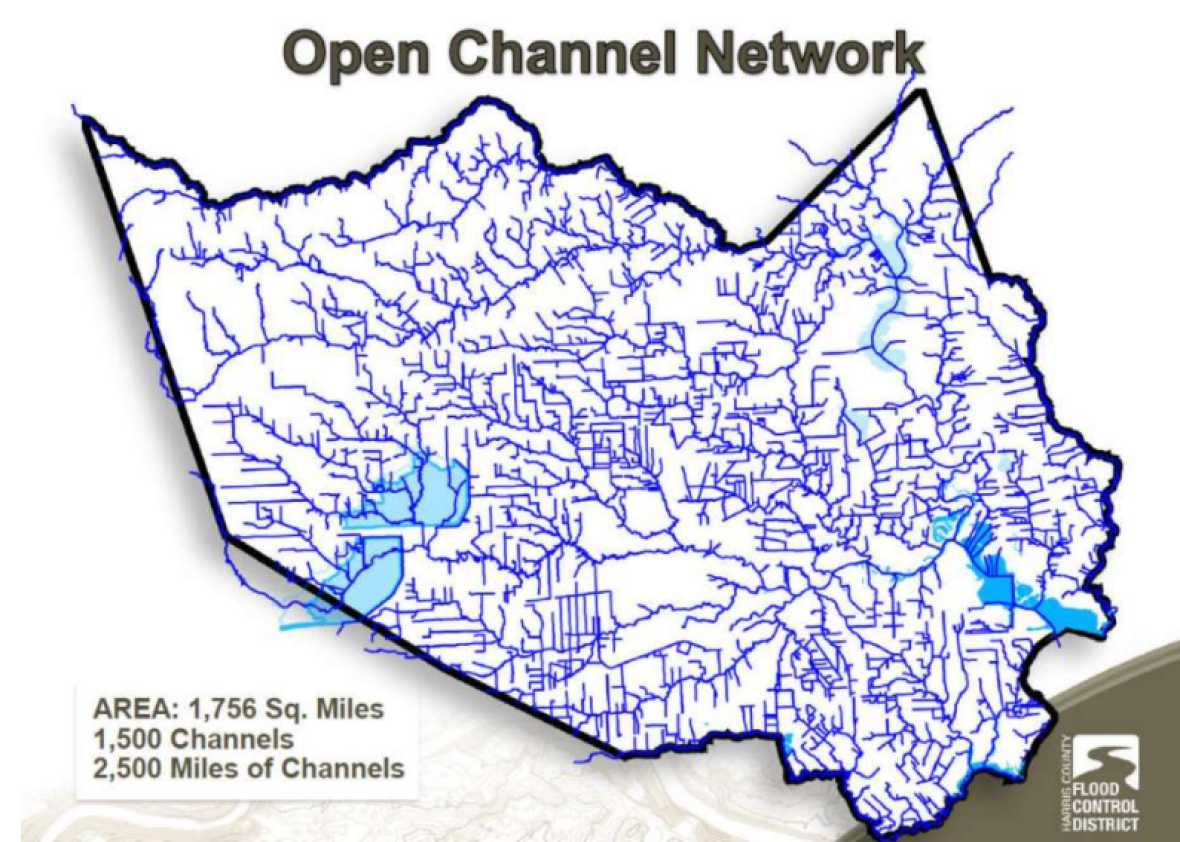

Storm surges come from the sea; a swollen river envelops a downtown along a predictable route. But the Houston metro area is nearly the size of Massachusetts. Harris County, which includes most of Houston, has 2,500 miles of channels. Everyone in Houston lives near a bayou; there is no “railroad track” stigma to these waterways. They are simply everywhere. And because the variance in rainfall totals from one part of the region to the next are running in the feet, it’s hard to anticipate which blocks will flood.

Harris County Flood Control District

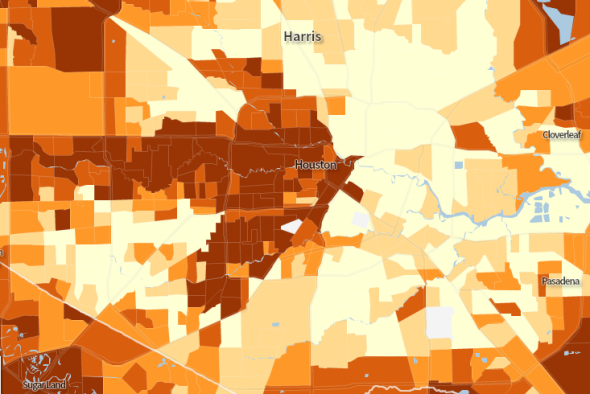

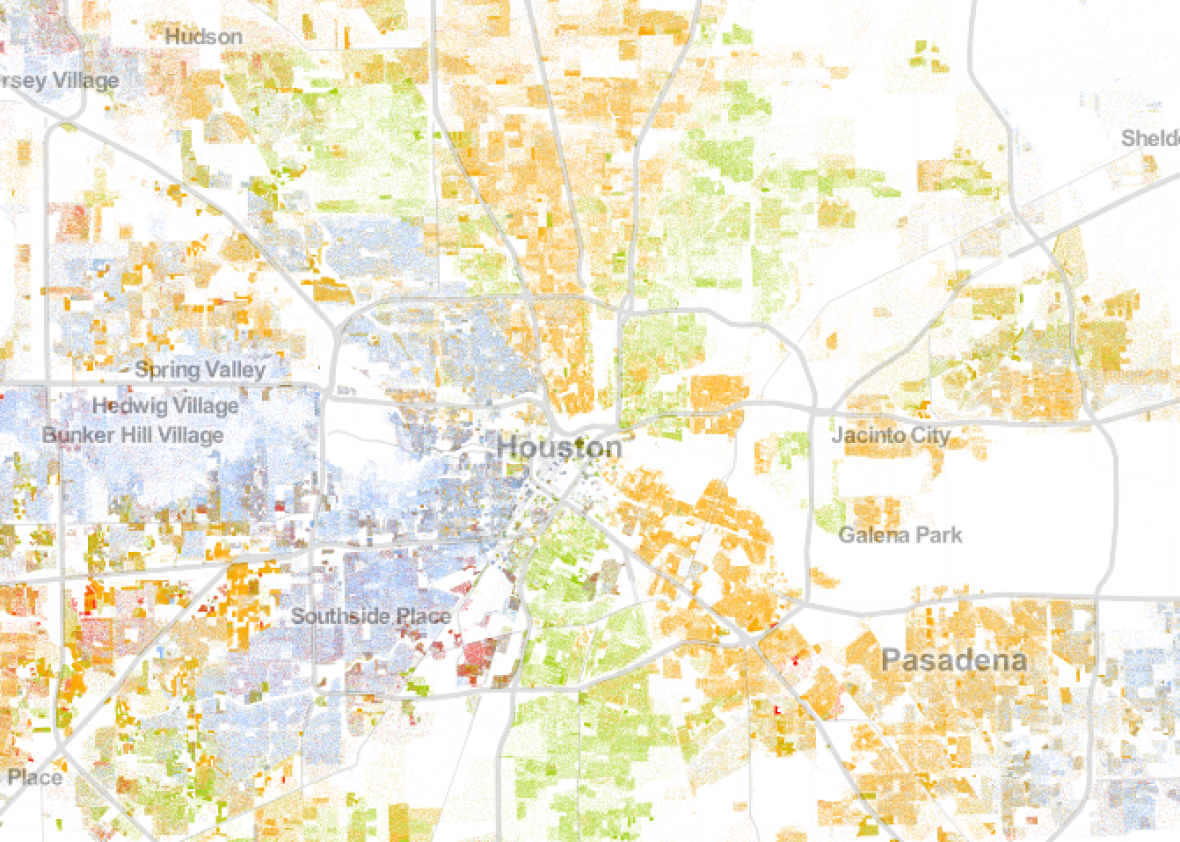

There is an assumption, forged by the experience of Hurricane Katrina, that natural disasters will do their worst to low-income neighborhoods of color.

At City Lab, Tanvi Misra writes: “Within cities, poor communities of color often live in segregated neighborhoods that are most vulnerable to flooding, or near petrochemical plants and Superfund sites that can overflow during the storm. This is especially true for Houston.”

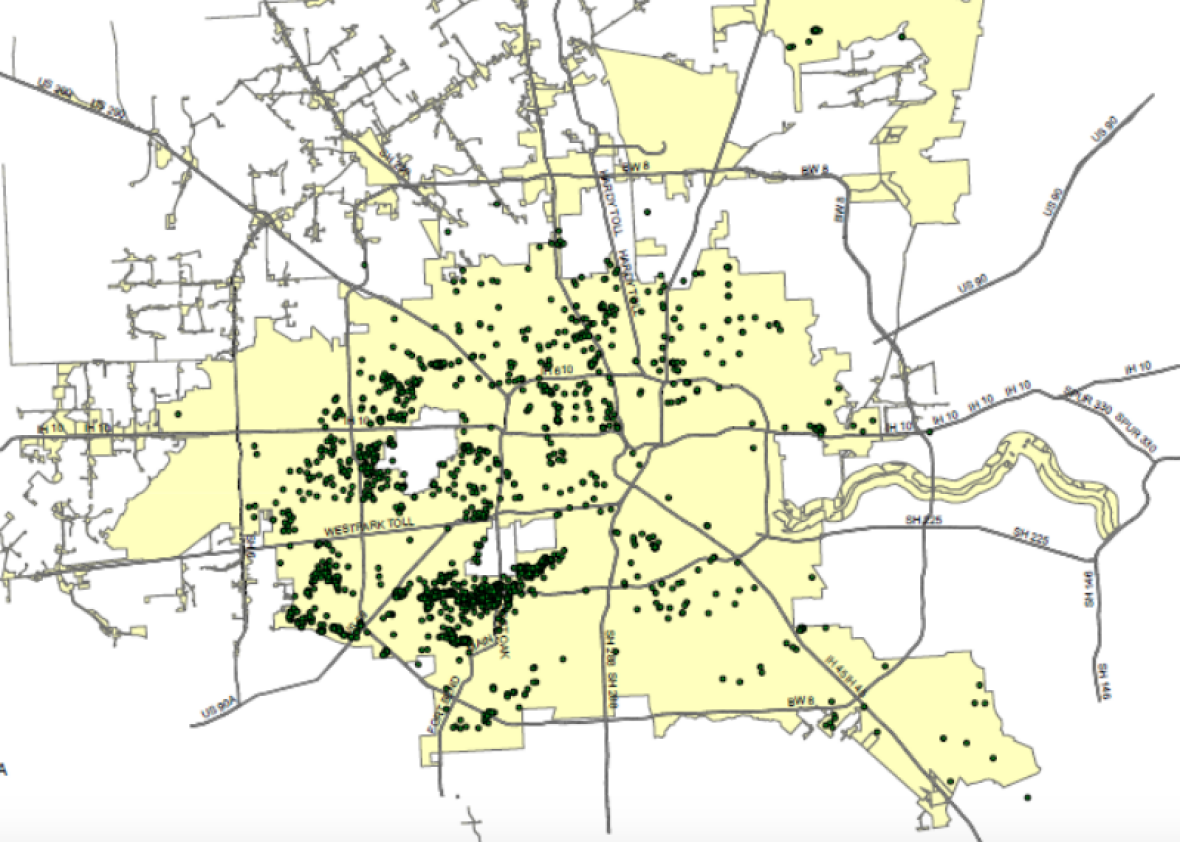

But actually, Houston’s floods have proven to be great equalizers. On the one hand, there are very poor neighborhoods in Harris County that have been hit hard, repeatedly, by flooding. Greens Bayou in Greenspoint has overflowed its banks three times in the past two decades, and nearly half the housing there is in the 100-year-flood zone after FEMA revised its Harris County flood maps in September. More than 1 in 3 residents lives below the poverty line. Some of them are among the nearly 1,000 Houston families who live in HUD-subsidized housing in the flood zone. This weekend, Greens Bayou overflowed again, causing mass evacuations and sweeping a family of six downstream as they tried to escape the swirling river.

At the same time, underwater houses in the flood zones adjacent to the two great Houston reservoirs whose dams protect downtown can go for more than $750,000. Some of the worst damage during the 2015 Memorial Day floods came in the sliver of high-income neighborhoods south of I-10 on Houston’s west side; among the worst-hit areas were the neighborhoods adjacent to Brays Bayou, where houses routinely sell for more than $1 million. The 2016 floods shut down the Exxon-Mobil corporate headquarters in the Woodlands.

U.S. Census Bureau

Racial dot map

We don’t yet have a good sense of which parts of the city are flooded this time around. We know that this storm, strengthened to new heights by an overheated atmosphere, has taken out the country’s second-largest refinery, the Exxon Mobil facility at Baytown. That’s ironic. But in the end, the consequences will be the same as they always are.

“The pain is greater in low income neighborhoods because they don’t have insurance and have no place to go,” says David Crossley, the founder of Houston Tomorrow, a nonprofit focused on Houston’s growth. He described seeing a neighbor, an artist with a flooded studio adjacent to a nice house, ripping out carpets and making repairs before the storm had even ended. “Someone who’s got a $600,000 house out in the suburbs can probably recover.”

Look over the Harvey rescue map and you start to see how, even if their houses are flooding at the same rate, the poor are less resilient. A diabetic out of medicine. An elderly woman with no spare oxygen tanks. A man in need of a dialysis treatment. The list of needs goes on. Seizure meds. Food.

It’s just easier for some people to get help.

That’s true now, and it will be even more true when the time comes to rebuild.