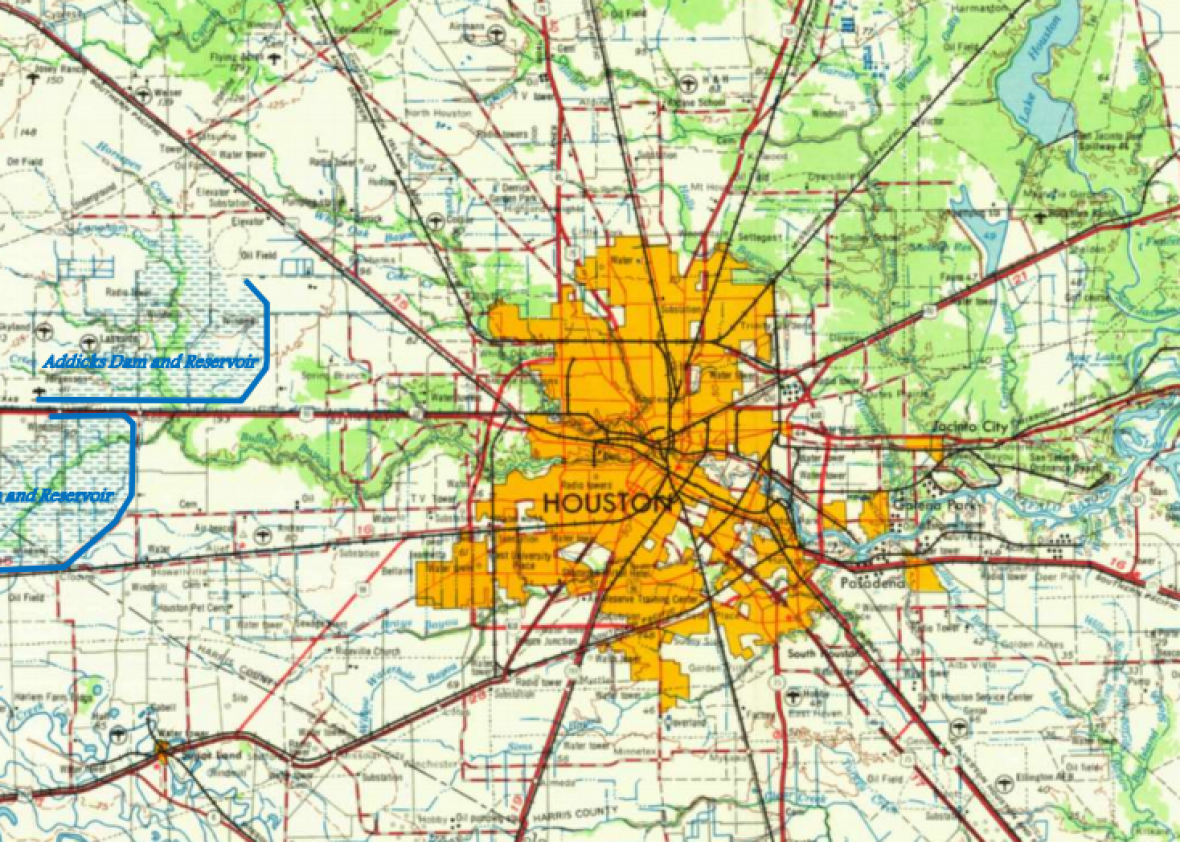

If you look at a satellite image of Harris County, Texas, where subdivisions cascading west into the Katy Prairie have helped make the Houston area the country’s fastest growing metropolitan region since 1980, you can see two large green splotches on either side of the Katy Freeway. These are the Addicks and Barker reservoirs, evidence of how Houston’s planning has been overwhelmed by unregulated urban growth and a storm no one thought possible.

On Sunday night, as Houston sank beneath record rainfall, the Army Corps of Engineers, which runs the reservoirs, announced it would begin releasing water from the dams. That means more water heading into Buffalo Bayou, the river that drains much of the Harris County watershed into the sea.

You may have seen photos of Buffalo Bayou: Normally it’s a small creek that winds through a lovely park in central Houston, running toward the Houston Ship Channel on the city’s eastern edge. On Sunday it was a sprawling mass of brown water, swallowing highways and neighborhoods in its tide. The bayou was expected to crest at 14 feet above its previous record high.

Army Corps of Engineers

Addicks and Barker were built to protect downtown Houston and keep water out of Buffalo Bayou. So why in the world is the Army Corps opening the gates?

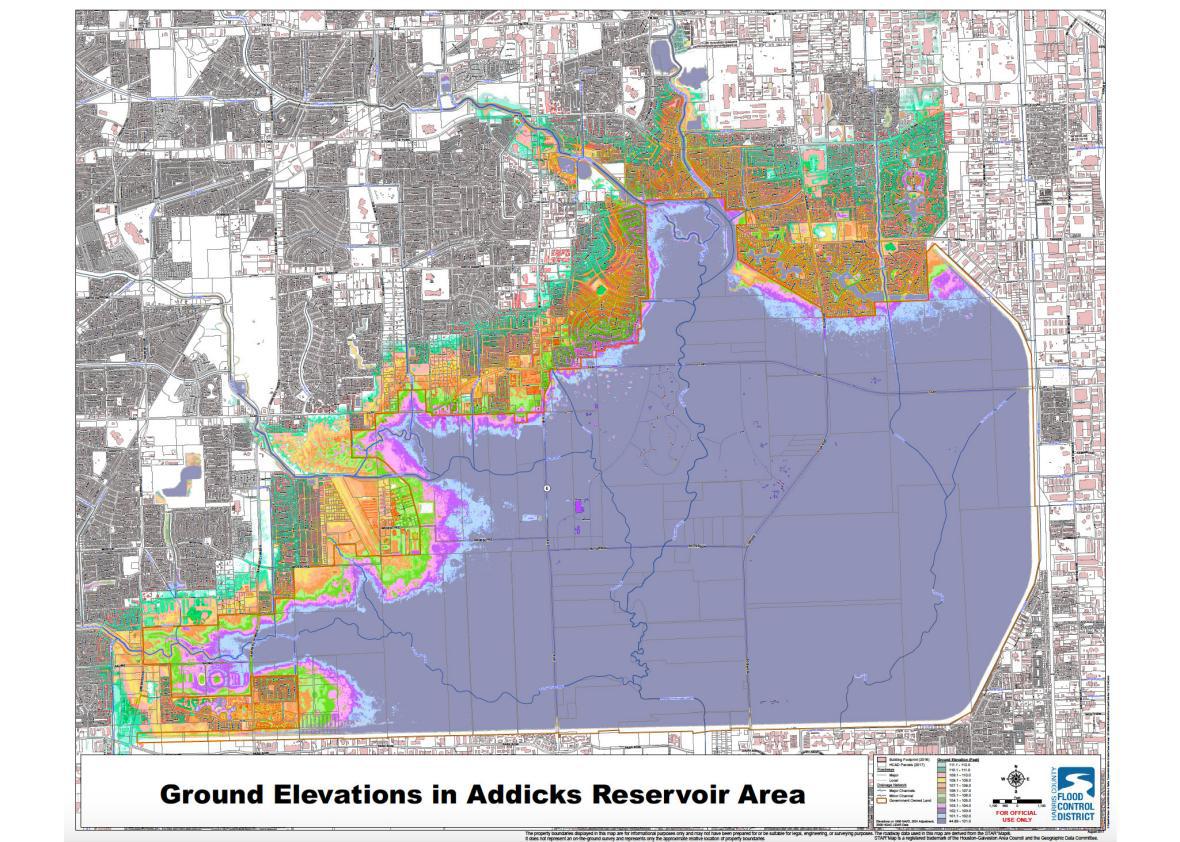

In part because even as Buffalo Bayou surges downtown, the back ends of the reservoirs have begun to push into residential neighborhoods upstream. The reservoirs are filling faster than they can empty, so despite the Corps releasing more water downstream, the pool is expanding upstream. The flooding is increasing on either side of the dams. There are three places for the water to go: through the dam gates, down the emergency spillways along the sides of the dams, and upstream into the neighborhoods. Officials think the water will likely go in all three directions, though ultimately it all ends up in Buffalo Bayou. It’s a balancing act to make sure this happens in the most controlled way possible.

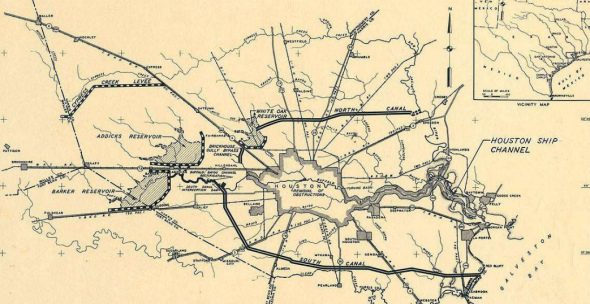

When Addicks and Barker were completed, just after the second world war, Houston had recently endured two cataclysmic downtown floods, in 1929 and 1935. The reservoirs—mostly dry, wooded areas with creeks running through them—could be plugged up to stall whole swaths of the watershed from reaching Buffalo Bayou.

Army Corps of Engineers

Army Corps of Engineers

But as development has sprawled west along the Katy Freeway, more and more water is being funneled into the region’s creeks, filling the reservoirs faster. “Of the 10 largest pools that have accumulated in the reservoirs, nine have occurred since 1990 and six of those were since 2000,” ProPublica wrote last year.

Meanwhile, developers swooped in and built tract houses up to the very brink of the reservoirs, which appear in dry times to be forests. It’s probably a very pleasant place to live, except when it isn’t. During last year’s Tax Day floods, those subdivisions on the reservoirs’ western edges flooded. Now they are flooding again. None are in the 100-year floodplain. Most are in the 500-year floodplain, areas that FEMA predicts will flood once every 500 years. They are not obligated to have flood insurance. They have flooded two years in a row.

Those homes should probably never have been built. Now they’ll be flooded for quite some time: “Homes upstream will be impacted for an extended period of time while water is released from the reservoirs,” the Corps wrote in a press release. The reservoirs will take between one to three months to drain.