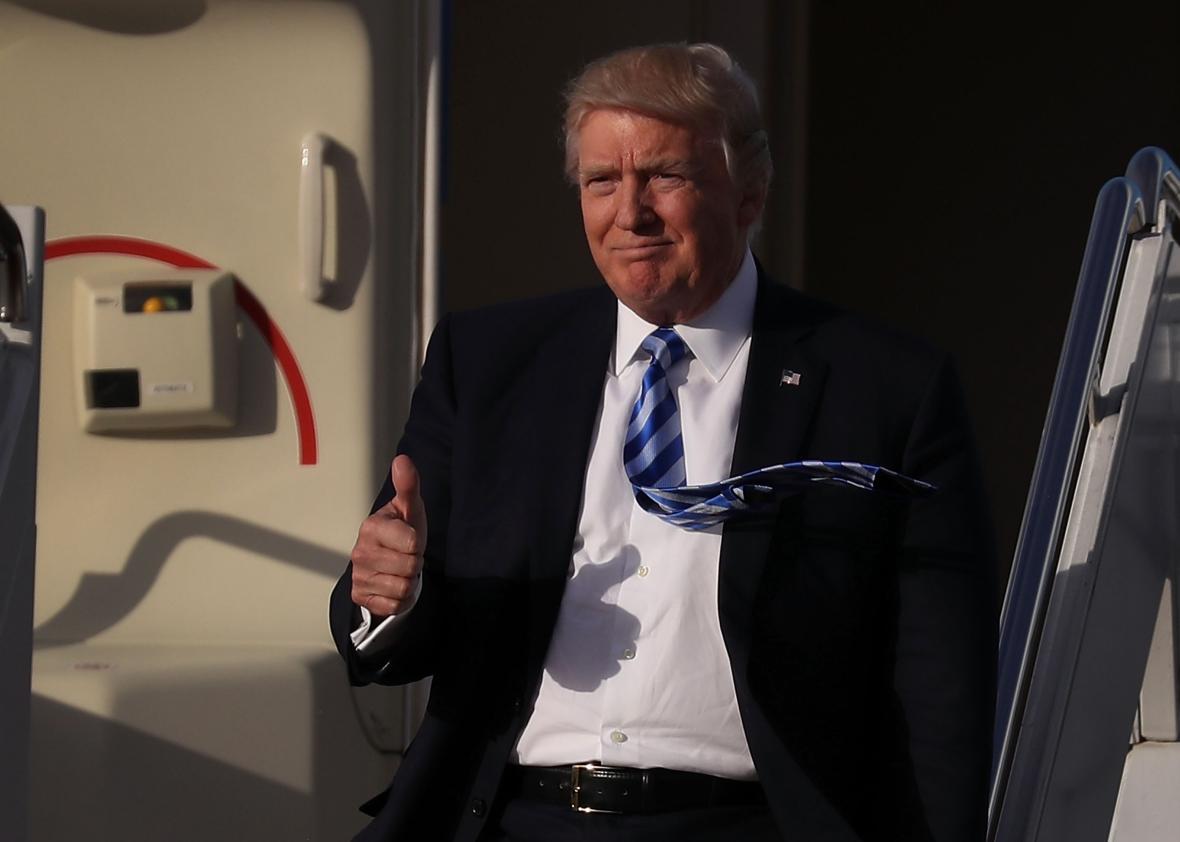

Donald Trump hasn’t even finished writing his tax plan yet, and yet it already looks poised to meet a humiliating death on Capitol Hill.

Like most things our Cheeto-in-chief touches, the package of tax cuts that the White House is preparing to unveil on Wednesday is shaping up to be a gaudy money-loser. According to the Wall Street Journal, Trump has told his staff to work up a scheme that would cut the top corporate tax rate by more than half, from 35 percent to just 15 percent, without worrying too much about how to pay for it. “During a meeting in the Oval Office last week, Mr. Trump told staff he wants a massive tax cut to sell to the American public,” the Journal reports. “He told aides it was less important to him that such a plan could add to the federal budget deficit.”

Would such plan waste trillions of dollars padding the pockets of Walmart and Exxon’s shareholders? Absolutely! Would that stop Republicans from supporting it? Probably not! But unfortunately for Trump, his plan to slash corporate tax bills has a fatal flaw: It’s probably forbidden under the Senate’s rules, and thus entirely incapable of passing Congress.

At least, so suggest some recent comments by George Callas, who serves as senior tax counsel to House Speaker Paul Ryan. Speaking at a panel event in Washington last week, which was previously reported on by the New Republic’s Brian Beutler, Callas dismissed the idea of passing a corporate tax cut without paying for it in pretty much the harshest terms a tax wonk can muster, calling it a “magic unicorn” at one point. Feisty!

“A plan of business tax cuts that has no offsets, to use some very esoteric language, is not a thing,” Callas said. “It’s not a real thing. And people can come up with whatever plans they want. Not only can that not pass Congress, it cannot even begin to move through Congress day one. And there are political reasons for that. No. 1, members wouldn’t vote for it. But there are also procedural, statutory procedural, legal reasons why that can’t happen.”

Those reasons have to do with the Senate’s budget reconciliation process, which Republicans will have to rely on in order to move any tax bill into law, assuming Democrats won’t sign on. The procedure prevents filibusters on legislation related to taxes and spending, allowing them to pass on a bare majority vote. But it comes with a catch: Any legislation passed through reconciliation can’t increase the deficit outside of the 10-year budget window. This restriction, known as the Byrd rule, is actually written into federal statute.

One way to get around the Byrd rule is to make tax cuts temporary. The budget-busting Bush tax cuts were set to expire after 10 years for precisely that purpose, and as it has become increasingly obvious that Republicans won’t be able to agree on a plan to reform the tax code without increasing the deficit, many have assumed they’d borrow from that old playbook.

But that only really works for individual tax cuts. During his appearance, a very exasperated Callas explained that, in order to satisfy the Byrd rule, corporate tax cuts would probably have to sunset after just two years, making them utterly pointless. Here’s how he put it:

Here is a data point for folks. A corporate rate cut that is sunset after three years will increase the deficit in the second decade. We know this. Not 10 years. Three years. You could not do a straight-up, unoffset, three-year corporate rate cut in reconciliation. The rules prohibit it. You might be able to do two years. A two-year corporate rate cut—I’ll defer to the economists on the panel—would have virtually no economic effect. It would not alter business decisions. It would not cause anyone to build a factory. It would not stop any inversions or acquisitions of U.S. companies by foreign companies. It would just be dropping cash out of helicopters onto corporate headquarters.

Tell us how you really feel, George.

Now, perhaps this is just the disaffected ranting of a tax-policy professional who doesn’t want the rest of the GOP to abandon his boss’s own tax reform plan. Maybe Mitch McConnell could come up with some kind of parliamentary maneuver to make Trump mega–corporate cuts a reality. But it’s awfully strong language, and signals that Trump’s 15 percent corporate tax rate may even be DOA in Paul Ryan’s House if he can’t find a way to pay for it.

As usual, the White House is doing a bang-up job.

* * *

For those interested, here’s a full transcript of Callas’ remarks. They’re pretty delightful.

I want to pick up on what Doug has said a couple of times talking both about the constraints of reconciliation rules as well as, Mark, you mentioning whether the White House might come out with a plan that has no offsets. It’s a very, very important point here. A plan of business tax cuts that has no offsets, to use some very esoteric language, is not a thing. It’s not a real thing. And people can come up with whatever plans they want. Not only can that not pass Congress, it cannot even begin to move through congress day one. And there are political reasons for that. Number one, members wouldn’t vote for it. But there are also procedural, statutory procedural, legal reasons why that can’t happen. Doug and Mark were both talking about reconciliation. I want to pick up on that and flesh that out a little bit because it’s very, very important.

There is, I call it a magic unicorn running around, and I think one of the biggest threats to the timeline on tax reform is the continued survival of magic unicorns. People saying “Well why don’t we do this instead?” when this is actually something that cannot be done. As long as that exists , it’s hard to move forward by getting people to go through with what the speaker refers to as the stages of grief of tax reform where you have to come to the realization that there are tough choices that have to be made and you cannot escape those tough choices.

What the reconciliation rules say—they don’t say that tax cuts have to sunset in ten years. They say that you cannot have a deficit increase beyond the 10-year window. Now, as Doug explained, if you have permanent tax reform that is fully offset with base broadening forever, you’re are fine. You don’t have to to have anything sunset under the reconciliation rules. You can have permanent tax cuts that are paid for in the out years. If you have legislation that has no offsets, no base broadening, so it’s just tax cuts, you either have to get Democrats to support it, which they will not, or you have to do it through reconciliation so that you can do it on a partisan basis with only Republican votes. Again, reconciliation says you cannot increase the deficit after 10 years. Here is a data point for folks. A corporate rate cut that is sunset after three years will increase the deficit in the second decade. We know this. Not 10 years. Three years. You could not do a straight up, unoffset, three-year corporate rate cut in reconciliation. The rules prohibit it. You might be able to do two years. A two year corporate rate cut—I’ll defer to the economists on the panel—would have virtually no economic effect. It would not alter business decisions. It would not cause anyone to build a factory. It would not stop any inversions or acquisitions of U.S. companies by foreign companies. It would not cause anyone to restructure their supply chain. It would just be dropping cash out of helicopters onto corporate headquarters.