It may already be time to pour one out for Paul Ryan’s beloved tax reform plan.

The House speaker’s scheme for overhauling the corporate tax code has been looking increasingly imperiled over the past couple months thanks to a steady onslaught by skeptical Senate Republicans. Ignoring Ryan’s pleas to “keep their powder dry,” lawmakers like Georgia’s David Perdue and Tom Cotton of Arkansas have trashed the proposal’s controversial centerpiece, an idea known as border adjustment that would effectively tax imports while subsidizing exports.

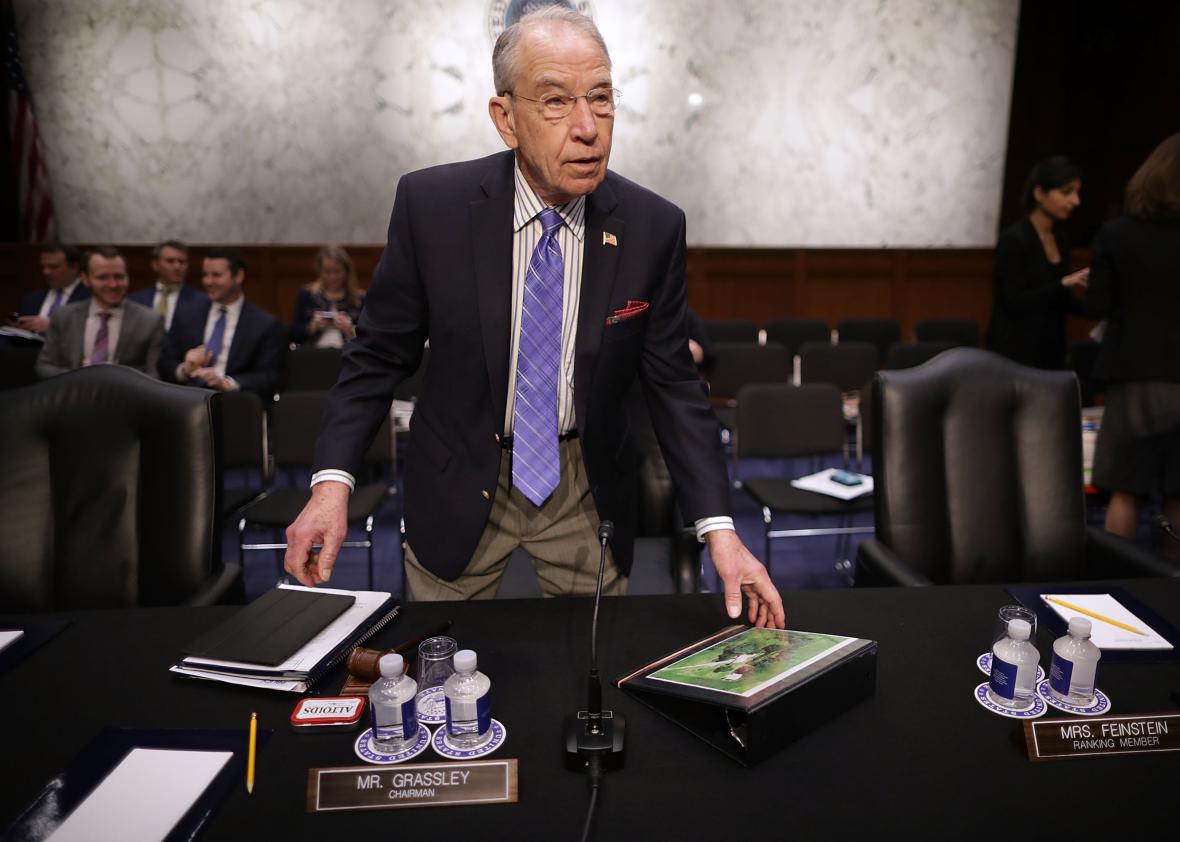

Opponents of the Ryan plan, especially retailers, have argued it would hurt American shoppers, who’d have to pay more for foreign-made goods—which is to say, pretty much 90 percent of their shopping cart at Walmart. A few members have suggested Ryan’s proposal would be dead on arrival in the upper chamber. “The House is talking about a tax plan that won’t get 10 votes in the Senate,” Sen. Lindsey Graham said back in February. But the most damning comments yet may have come from Senate Finance Committee member Chuck Grassley, who according to Bloomberg BNA told reporters this week that border adjustment opponents didn’t have “anything to worry about” because the committee wasn’t going to indulge Ryan’s plan.

“If the Senate starts working on a tax bill of its own, you aren’t going to hear anything about border adjustment in the Senate Finance Committee,” Grassley said.

Those words sound a lot like a death sentence. Grassley is an influential former chairman of the Finance Committee, which would play a central role in any GOP tax reform effort. If he says it’s a nonstarter, it’s probably a nonstarter. (The current chairman, Utah Sen. Orrin Hatch, has been more diplomatic, saying that while the committee would “certainly have to look at it,” he had “real reservations” about border adjustment and that the idea would be “difficult” to push through the Senate).

How did Ryan misfire so badly? For all the flak I’ve given the man for his ostentatious faux wonkish-ness, his main mistake this time seems to have been embracing a clever, economically elegant idea that’s way too out there to survive contact with Capitol Hill, or any other part of the real world.

Border adjustment is the key element of Ryan’s plan to replace the current corporate income tax with what’s known as a Destination Based Cash Flow Tax. The DBCFT had unusually nonpartisan roots. Its chief intellectual architect in the U.S. was University of California–Berkeley economist Alan Auerbach, a former adviser to John Kerry’s presidential campaign, who outlined the idea in a white paper published by the liberal Center for American Progress. Auerbach envisioned the DBCFT as a way to modernize corporate taxes for a world where companies like Google and Apple avoid the IRS by shifting their profits overseas to countries with lower rates.

In essence, the DBCFT would have turned the U.S. itself into a gigantic corporate tax haven, like Ireland on steroids. First, Washington would effectively tax imports by preventing companies from deducting them as business expenses. At the same time, the U.S. would subsidize exports by exempting them from taxation entirely. While this sounds like some sort of protectionist fever dream come to life, Auerbach and many other economists argue that the combination would cause the value of the dollar to rise enough to negate any effects on trade. Walmart might have to pay a de facto 20 percent tariff on T-shirts from China. But thanks to a rising dollar, those T-shirts would cost 20 percent less to buy from manufacturers, meaning the company wouldn’t have to eat any extra costs or pass them on to customers.

What does this have to do with making the U.S. a tax haven? For starters, taxing all sales in the U.S., including imports, would theoretically kill the incentive for companies that do most of their business here—like, say, drugmakers or Burger King—to move their corporate headquarters overseas as a tax-avoidance scheme. At the same time, exempting all exports from taxes may have encouraged some foreign companies to set up shop here. That’s because most of the world operates on what’s known as a territorial system, where governments tax companies only on profits generated within their own borders. (The U.S. currently has a modified worldwide system, meaning we try to tax corporations on profits earned anywhere.)

In a DBCFT world, if Mercedes moved a car plant to the U.S. and then shipped those cars elsewhere, they’d pay neither German nor U.S. taxes. Would moves like that happen often in practice? Not necessarily—companies tend to care more about labor costs than taxes when picking spots for factories, which is why low-tax Ireland tends to attract holding companies that barely exist beyond paper rather than actual production facilities. But at least companies would have a reason to call the U.S. home rather than flee.

Advocates of border adjustment would sometimes hint at all this by suggesting it would make the U.S. more globally competitive. As House Ways and Means Chairman Kevin Brady put it to Vox, the plan would create “major incentives for businesses to locate that new plant, that new research, that new intellectual property here in the United States, whether they are trying to access the U.S. market or the world market.”

But border adjustment was a key part of the Republican tax plan for another reason: It would raise a lot of money, more than $1 trillion over a decade according to policy analysts, a windfall that would help finance a massive cut bringing the top corporate rate from 35 percent to just 20 percent. Because that revenue would come from a tariff that would be balanced out by currency adjustments, in a lot of ways it looked like free money. Assuming the dollar rises in value, the losers aren’t Walmart or shoppers or even major exporters, like farmers, who are spared the tax. Instead, companies that earn a lot of profits overseas in foreign currencies (think Apple, which sells a lot of phones in China and tends to keep its profits abroad) and investors that hold foreign-denominated assets (think anybody who owns European stocks) would bear the brunt of the DBCFT.

Unfortunately for Ryan and fans of academically advanced taxation concepts, retailers like Walmart and Lowes don’t feel like risking their existence on an untested macroeconomic hunch that the dollar will appreciate in response to a combination of tariffs and subsidies. If it doesn’t, they’d potentially be forced to tack on the cost of border adjustments to their merchandise—if they didn’t hike their prices, they’d potentially end up with tax bills larger than their profits. And so companies have attacked the DBCFT as a stealth sales tax. Perdue, the former CEO of Dollar General, has said that “a border adjustment tax is a tax on low income and middle-income consumers—it hammers them.” Cotton, meanwhile, has called the notion that the dollar will appreciate “a theory wrapped in a speculation inside a guess.” The Arkansas senator added, “Just because an economist slaps an equation on a blackboard doesn’t make it real. I’m concerned that these predictions simply won’t pan out.”

It’s tempting to characterize the foundering of the DBCFT as parochial special-interest politics winning out over sound policy thinking. But whether or not Cotton has carefully thought through the ins and outs of this issue, he actually has a point. First, not every country allows its currency to float freely against the dollar (see: China), which means textbook theories based on freely adjustable exchange rates shouldn’t fully apply. Currency traders might also hesitate to price in the tax change, because it’s not obvious it would be permanent. There’s an active debate about whether the border adjustments envisioned as part of the DBCFT would violate World Trade Organization rules. Given that the whole point would be to make the U.S. a destination for legal tax avoidance, it would almost certainly draw challenges from foreign governments, putting its long-term prospects in question. It stands to reason as well that the prospect of a rapidly appreciating greenback would affect the demand for dollar-denominated assets, which would further mess with foreign exchange rates in hard-to-predict ways.

So, the Ryan plan’s naysayers aren’t wrong when they fret about unintended consequences. In any event, their fears seem to be carrying the day, as tends to happen when people propose massive public policy changes that could potentially hurt powerful stakeholders. DBCFT, we hardly knew ye.

Giphy