Last month, the owners of Pssst, a nonprofit art space in the East Los Angeles neighborhood of Boyle Heights, announced they would close their space in the face of “constant attacks” and “persistent targeting,” both online and in person, from anti-gentrification activists.

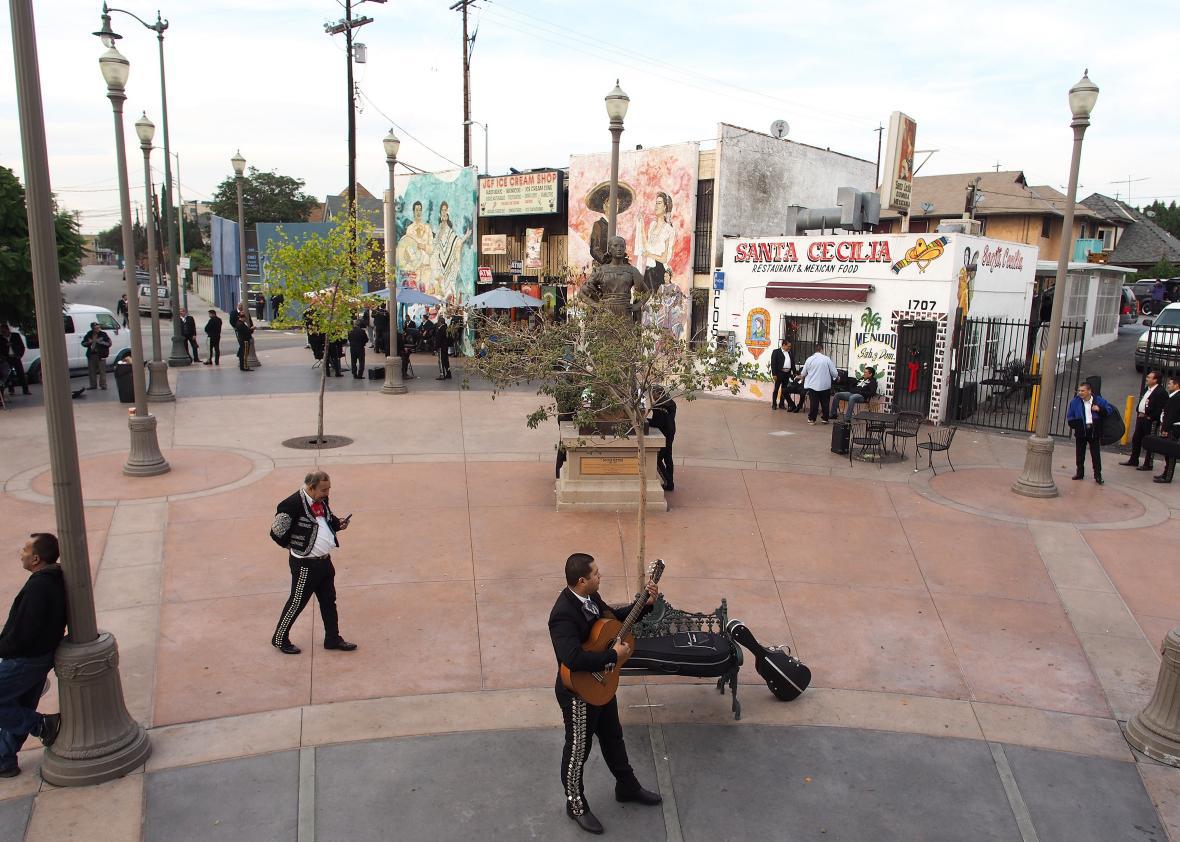

A pair of neighborhood groups, Defend Boyle Heights and the Boyle Heights Alliance Against Artwashing and Displacement, celebrated the shutdown. It was a victory in a long campaign waged by tenants groups in the predominantly Latino, working-class neighborhood against art galleries, which they see as the “shock troops of gentrification.” More broadly, it was a sign of just how high tensions over housing run in Los Angeles, which has by some measures the worst affordable housing crisis in the country.

On Tuesday, Angelenos vote on Measure S, which may be the most significant anti-development measure since voters opted in 1986 to freeze new building on the city’s low-slung, transit-rich commercial corridors. If it passes, the measure—also known as the Neighborhood Integrity Initiative—would essentially outlaw large, new developments in Los Angeles for two years, halting the city’s evolution in its tracks.

In some ways, the problem in Los Angeles is familiar from other cities: rising population, low growth in the housing stock. But zoning in Los Angeles is infamously restrictive. As the planner Greg Morrow has shown, the city zoned itself into a housing crisis. Just 50 years ago, the city’s residential “capacity”—how many units could legally be created, as of right, under existing zoning law—could have housed 10 million people. Los Angeles is now zoned to house at most, at an absolute maximum hypothetical build-out, 4.2 million people. The current population is 3.9 million. It’s no accident that as many as 1 in 4 new units between 2011 and 2016, according to the Lewis Center at UCLA, were built using the kind of zoning exceptions that Measure S would outlaw. Los Angeles is looking at cutting its already underperforming housing production by as much as 25 percent.

Those restrictions have sent development sprawling throughout the Southland, lengthening the nation’s longest commutes and worsening traffic. Bad traffic, in turn, is used by anti-development advocates as evidence of overbuilding. And so on.

The primary sponsor of Measure S is the AIDS Healthcare Foundation. Why the organization’s president, Michael Weinstein, has decided to spend more than $5 million of public-health money curtailing the supply of housing in Los Angeles is a question that remains largely unanswered despite his talk of social justice. “AHF is squandering millions of dollars that should be spent on HIV prevention and treatment,” the city controller said last month. The foundation did not respond to a request for comment.

The measure’s natural allies are the same NIMBY homeowners who have for decades used development restrictions to hike the value of their investments and impoverish their newer and poorer neighbors who dump their incomes into overcrowded rental apartments. They include people like Richard Close, the president of the Sherman Oaks Homeowners Association (i.e., a representative of one of the city’s comfortable neighborhoods), who told KCRW that “Measure S is about saving our communities.”

Los Angeles is actually a city of tenants. Most Angelenos don’t have a nest egg whose value rises when supply falls. Only New York has a lower percentage of homeowners among large U.S. cities. But the rhetoric boosting Measure S—and the phony, fearmongering “eviction notice” mailers that supporters have sent around the city—has a crossover appeal on the left, where tenant groups often oppose big, new developments, fearing rising rents, the loss of local businesses, and finally, their own evictions. While Measure S is opposed by Mayor Eric Garcetti, California Gov. Jerry Brown, and the local Democratic and Republican parties, it has the support of the L.A. Tenants Union.

Developers don’t call their projects “catalysts” for nothing. It’s not for nothing that they boast about the higher property values that follow big condo buildings when they try to convince cities to grant exemptions from the zoning code. It’s true that a big development can have a transformative effect, bringing amenities like a fancy grocery store (and a density of cash-rich gentrifiers) that make a neighborhood immediately more desirable and expensive even as it causes rents citywide to inch a little lower. And because development so rarely comes in big, market-swinging bursts, tenants in L.A. haven’t seen new supply lowering demand in their own neighborhoods.

But if you bring enough units to market, the rent does go down. It’s happening in New York City now, and it could happen in Los Angeles. But it won’t happen if Measure S passes.

Which brings us back to Boyle Heights. The benefits of the Neighborhood Integrity Initiative will accrue largely to homeowners (and drivers looking for parking spaces). The constriction of the housing supply will hurt tenants. But if the measure passes, it’ll be thanks to their support.