The Cubs won the World Series, Donald Trump is the president-elect, and the rent in New York appears to be falling.

In October, the share of New York City rentals that took a price cut, according to the listing tracker Streeteasy, topped 42 percent—the highest level since December 2010. The real estate firm Citi Habitats, which draws data from its own listings, reports that the vacancy rate in Manhattan has climbed to 2.1 percent, its highest level since 2009. Both of those indicators, in other words, are back in Great Recession territory. “It’s a renter’s market right now,” says Chris Lee, the director of sales at Triplemint, a real estate startup.

We don’t know yet why that is, or how long it could last. Certainly, rents have outpaced incomes. White-collar tenants are less geographically selective than they used to be. New construction has caught up with demand. But whatever the reason, it looks like rents are about to dip … and then some.

It is hard to overstate the impact of New York’s high residential rents. They all but elected mayor Bill de Blasio, whose campaign’s theme was correcting for inequality. They have driven homelessness to record levels and continue to monopolize the disposable income of millions of New Yorkers. They have caused dozens of commentators to question the city’s very identity as a haven for the castoffs and dreamers of middle America and strivers from the rest of the world.

And because the problem of high rents is so general to American cities right now, if New York’s rental bubble is about to pop, it may offer a lesson to places like Los Angeles.

First, a caveat: It’s hard to generalize about rents. Different brokerages pull data from different stocks of apartments and report different findings. Some say New York’s rents are already falling faster than any high-cost market in the country. Most say that prices have softened or stabilized.

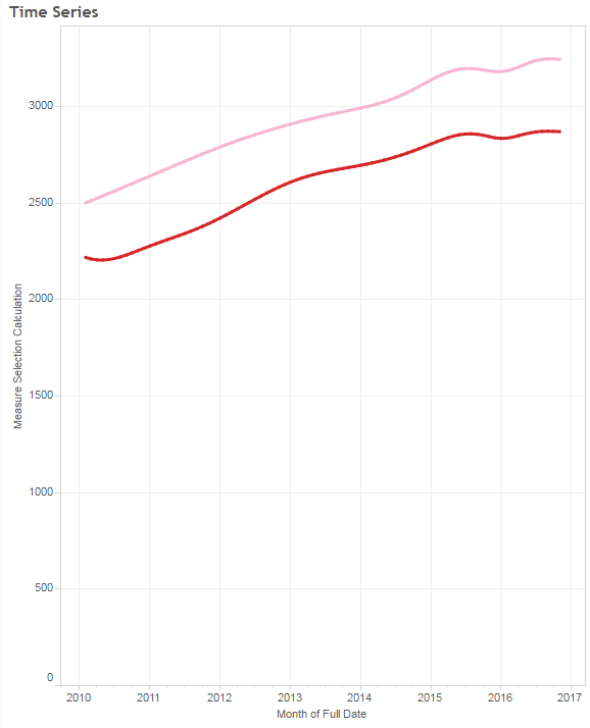

But there’s reason to suspect that rents are on the cusp of a larger decline. That discounts and vacancy are at a seven-year high is part of it. But charts like the one below, from Streeteasy, that show rents reaching a plateau are likely a little behind the times.

Streeteasy

For one thing, part of the shift toward a buyers’ market has been disguised by widespread and growing “concessions”—landlords offering a month or two of free rent, for example, but leaving the monthly rate the same. In August, the New York Times reported on this phenomenon in Downtown Brooklyn, where a massive building boom has seemingly created a new skyline overnight. Nearly every building was offering one to four months of free rent.

It’s not just Brooklyn. According to Citi Habitat, 27 percent of Manhattan transactions featured a “concession” in November 2016—meaning real, lower rates for tenants aren’t being reflected in rent data. The concession rate has more than doubled since last year. Douglas Elliman, another broker, reports that rents are down in Brooklyn and Manhattan and also says that concessions have doubled in both boroughs from this time last year.* That is not part of the normal seasonal downturn in rents that happens at year’s end.

The other thing about market reports is that they are out of date. They show how things were going six to eight weeks ago. A sample of December listings shows an even sharper decline.

Urban wonk Stephen Smith, tweeting at Market Urbanism, has been collecting some of these listings. A Williamsburg one bedroom down to $2,500 from $3,500 in 2014—with a free month’s rent. An East Village one bedroom at $2,695—same as its rent in August 2009—and still unrented. A Hell’s Kitchen one bedroom, rented in 2014 for $3,750, down to $3,250, and still unrented. A two bedroom in Downtown Brooklyn down 30 percent since July—with two free months. A two bedroom in Williamsburg down $600 from last year, with two months free. A brand-new apartment overlooking Prospect Park, down more than $600 to $2,940 since it was first listed in July—and still available. A studio in the West 30s listed for less than it rented in 2013.

A three bedroom on the Upper East Side that, after eight price chops, is back to its 2010 rent—and down more than $1,000 since 2013. Oh, and the apartment comes with two free months—on a 16-month lease (which, in a city where rents were rapidly rising, would be more favorable to tenants).

These are anecdotes, of course. I haven’t been to these apartments; maybe they’re in bad shape. Maybe their landlords got lucky, or greedy. But Smith’s point is that this is all happening day by day. Those rent-price graphs are already propped up by developer concessions. And they haven’t factored in drops like these.

What’s more, if it is a glut, the glut is likely just beginning. 2015 was a record year for residential building permits in New York City—with developers pressed by expiring loopholes, the city authorized nearly 35,000 new units in the second quarter and nearly 10,000 more in the fourth. Total permits topped 50,000—more than any year since the early 1960s. And many of them aren’t done yet—according to the U.S. Census Bureau, about half of all multiunit projects take more than 13 months from the permitting date to be completed. One look at the skyline will tell you that the city is still very much in the throes of a building boom.

That skyline in Downtown Brooklyn? That’s what a tenant’s market looks like.

*Correction, Dec. 14, 2016: This post originally misspelled Douglas Elliman.