As 2014 wound down, Uber Chief Executive Travis Kalanick laid out an ambitious vision for the coming year. “In 2015 alone,” he wrote on the company’s blog, “Uber will generate over 1 million jobs in cities around the world.” Less than one month along the road, Uber has settled on its message to potential workers for achieving the ambitious 1 million target: Driving for Uber is a fun, flexible, and reliable way to earn a living.

On Thursday, Uber released a comprehensive new study on driver earnings and satisfaction in support of that narrative. The report, co-authored under contract by Princeton University economist and former Obama administration adviser Alan Krueger, and Jonathan Hall, the company’s head of policy research, contains a lot of fresh information. For example: Uber paid out $656.8 million to its U.S. drivers in the last quarter of 2014. The number of active drivers on its low-cost UberX platform (those giving at least four rides a month) is growing exponentially. Half a year after joining Uber, 70 percent of drivers are still actively using its system.

The points that are really vital to Uber’s storyline, though, come from a survey conducted on its behalf by the Benenson Strategy Group in December 2014. It’s good to take what follows with a grain of salt. Just 11 percent of those surveyed, or 601 drivers, actually responded, and they were financially incentivized to do so. Still, the results were impressive. Seventy-eight percent of Uber drivers are “satisfied” with their experience driving for Uber. Seventy-one percent report their income has improved. And 73 percent say they would rather have “a job where you choose your own schedule and be your own boss” than “a steady 9-to-5 job with some benefits and a set salary.” Now combine that with Uber’s own data, which show that 81 percent of drivers work part time (51 percent work between one and 15 hours per week; 30 percent work 16 to 34 hours). The picture emerging is clear: People driving for Uber like setting their own schedules and working hours convenient to them, and overwhelmingly, they do that.

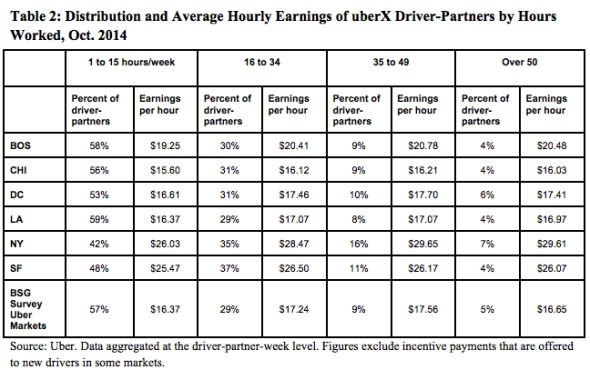

But here’s the single most important insight Uber has to offer: On a city-by-city basis, UberX drivers seem to earn about the same amount per hour, on average, no matter how many hours they choose to work.

Uber

This is a big deal. The concept of a “part-time pay penalty”—that people, especially women and those in low wage jobs, get paid disproportionately less when they work below 40 hours a week—is well documented. Uber’s data on average hourly earnings suggest that the penalty just isn’t there. Or, as the study puts it, “The finding that hourly earnings for Uber’s driver-partners are essentially invariant to hours worked during the week … makes Uber an attractive option to those who want to work part-time or intermittently, as other part-time or intermittent jobs in the labor market typically entail a wage penalty.” It’s the point that ties everything Uber is promising prospective drivers—a flexible, empowering, and reliable job—together.

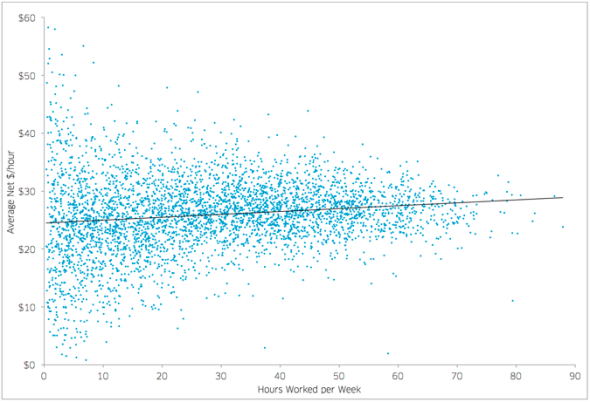

So it’s kind of a shame that those figures on average hourly earnings might also be some of the most misleading in the entire report. Here’s why I think that. About two months ago now, Uber released some data on several thousands of its drivers in New York City. As part of that, the company created a scatter plot showing how the average net hourly earnings of drivers varied with the total number of hours they worked each week. For full-timers the average hourly earnings were fairly consistent. But for part-timers, and especially for those working between one and 15 hours, the data looked like a shotgun blast (imagine the shooter standing to the right):

Uber

When I first spoke with Krueger about the study, I mentioned this. After all, the fact that the average of drivers’ hourly earnings in the same city is the same doesn’t mean that there isn’t also a great deal of variation. As the graph above shows pretty well, trend lines and averages can mask a lot. Krueger’s response was that “the requirements in New York City are different than in many other areas.” This is true. To drive for Uber in the city, you have to be licensed with the Taxi and Limousine Commission. But that alone doesn’t seem to explain why the earnings data for part-time drivers in other cities might not follow the same pattern. (Side note: It would help if the study included standard deviations for these averages, but it doesn’t, and when I asked Krueger for that he said he didn’t have it.)

This isn’t to say the study should be discounted entirely. As Danny Vinik points out at the New Republic, “whatever their actual net income, drivers are, on average, happy with their employment situation.” That’s good news for Uber and good news for the people it’s putting to work. Moreover, Uber’s driver base has continued to grow even as the economy has strengthened in recent months, suggesting that the supply of contract workers for Uber and other “on-demand” economy companies like it might not dwindle as we head back to full employment. Working for Uber is flexible. It pays pretty well. And at least based on one Uber-commissioned survey, drivers are happy. But are the earnings always reliable? That we still can’t say.