If there’s oil in them thar hills, it should stay there. That’s the message of a new study that argues the bulk of remaining fossil fuels should remain in the ground, rather than being mined, fracked, extracted, or tapped.

The study, published by a team of British scientists in Thursday’s edition of Nature, issues a profound warning about the modern fossil fuel industry:

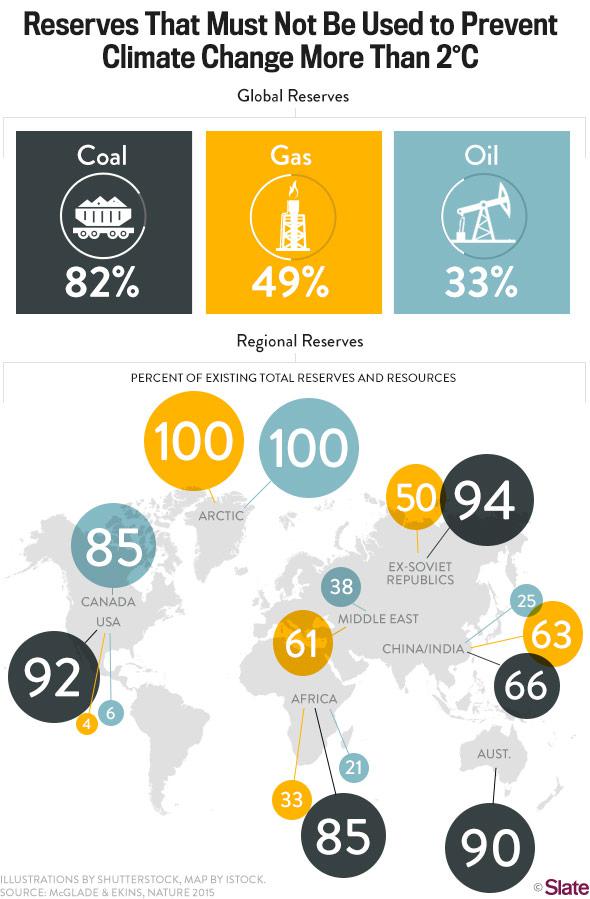

[A] stark transformation in our understanding of fossil fuel availability is necessary. Although there have previously been fears over the scarcity of fossil fuels, in a climate-constrained world this is no longer a relevant concern: large portions of the reserve base and an even greater proportion of the resource base should not be produced if the temperature rise is to remain below 2°C.

This is the first study to highlight which specific national reserves must be abandoned in order to keep global warming in check, with trillions of dollars in assets on the line. The idea that fossil fuel companies could cause a major economic crash, should their reserves be deemed worthless, inspired the Bank of England to launch an inquiry last month.

Meanwhile, currently plummeting oil prices—down more than 50 percent over the past six months—may be providing a glimpse into a future of the sort described in the new study. In recent weeks, calls (1,2,3,4) for using the recent drop to implement carbon taxes and eliminate subsidies to oil companies have grown louder. New drilling permits have plunged, and coal prices have also fallen substantially, putting additional burdens on a faltering industry.

To come up with the new numbers, the research team examined the “economically optimal” pathway for global curtailment of fossil fuel extraction. The results showed wide variations regionally, largely in proportion to the expected cost of mining and drilling in various parts of the world. For example, the study is harsh on the future of Canada’s tar sand oil mines, noting that under the optimal scenario, production “drops off to negligible levels after 2020.” Coal, the most carbon-intensive fossil fuel, also fares particularly poorly worldwide, though anticipated growth the North American natural gas fracking industry “plays an important part in displacing coal” in the study’s main scenario.

Most notable, however, is the implications for the Arctic. “All Arctic resources should be classified as unburnable,” the study warns. That doesn’t leave much room for leeway. Later this year, Shell is planning to drill for oil in Arctic waters north of Alaska. Russia already has a rig operating in its Arctic territory.

Chart by Slate staff.

The new study is also pessimistic about the potential of long-hoped-for solutions like carbon capture and storage to meaningfully offset industrywide emissions. Effective and affordable CCS isn’t likely to appear before 2025, so factoring it in only allows an additional 6 percent of fossil fuel reserves to be exploited.

The work echoes and builds upon other recent efforts, most notably from the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. In its latest comprehensive report, the IPCC said that only a finite amount of carbon—the Earth’s “carbon budget”—could be released from the burning of fossil fuels to preserve a 50-50 chance of staving off “dangerous” human-caused climate change, defined as a rise in global temperatures beyond 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

The authors of the new study write that “policy makers’ instincts to exploit rapidly and completely their territorial fossil fuels are, in aggregate, inconsistent with their commitments to this temperature limit.”

However, a true commitment to limiting the worst of climate change would “render unnecessary continued substantial expenditure on fossil fuel exploration, because any new discoveries could not lead to increased aggregate production.” Basically, the study says that any further investment in the fossil fuel industry, anywhere in the world, is indefensible. We can use the fuels that are cheapest to harvest, but even then, only to further the transition to carbon-free sources of energy.

Despite fresh rhetoric on climate change action, the world’s two leading economies, the U.S. and China—never mind the major oil companies—have not yet put their money where their mouths are, so to speak. Sure, some fossil fuel burning is absolutely necessary to encourage lowest-cost development of basic in places around the world, like India and sub-Saharan Africa, where millions still live in energy poverty. But for the rest of us, the time has arrived to turn our backs on continued fossil fuel use.