The United States and China—the world’s biggest contributors to climate change—just produced a game changer.

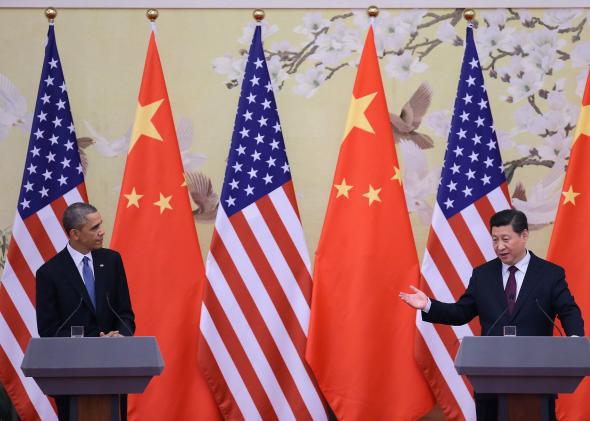

Leaders of the two countries jointly announced ambitious new targets in Beijing on Wednesday. In doing so, the superpowers set an example for the rest of the world at a crucial moment in history, removing a key “you first” obstacle to global action on one of the planet’s most pressing problems.

Together with new pledges by the European Union, the new targets by the U.S. and China comprise more than half of global emissions. If achieved, that means the world would stand a decent chance of deviating from a business-as-usual scenario. That scenario—which the world has followed for years now—would have all but ensured unfathomable changes to coastlines and ecosystems in the span of a single lifetime.

But beyond the emissions reduction pledge, the change in tone is significant. The move is a turning point for two nations that have long been at odds on climate. The New York Times reports the agreement was hashed out in secret over a period of nearly a year. The main objectives will become the centerpiece of global warming action for both nations for decades to come. From the Times:

Mr. Obama announced that the United States would emit 26 percent to 28 percent less carbon in 2025 than it did in 2005. That is double the pace of reduction it targeted for the period from 2005 to 2020.

China’s pledge to reach peak carbon emissions by 2030, if not sooner, is even more remarkable. To reach that goal, Mr. Xi pledged that so-called clean energy sources, like solar power and windmills, would account for 20 percent of China’s total energy production by 2030.

It’s impossible to overstate the deal’s significance for the rest of world. The announcement was made at a roundtable of Asia-Pacific countries. Later this week, leaders from the G20 group of major industrialized nations will assemble in Australia, and Wednesday’s announcement all but ensures that climate change has shot to the top of the agenda. Next month, climate negotiators from around the world will meet in Lima, Peru, in the last major meeting before an expected global climate agreement in Paris in 2015. The U.S.-China deal is sure to motivate additional pledges and actions by other countries.

“We hope to encourage all major economies to be ambitious—all countries, developing and developed—to work across some of the old divides, so we can conclude a strong global climate agreement next year,” said Chinese President Xi Jinping.

A fact sheet circulated by the White House said the announcement was “part of the longer range effort to achieve the deep decarbonization of the global economy over time.” The language “deep decarbonization” is a signal that the White House considers ambitious action on climate change to be realistic, as reflected in a U.N. report of the same name earlier this year.

In many ways, this is the day climate campaigners have been waiting for. The two nations were under growing pressure from their domestic constituencies to take action. The announcement came two months after the biggest rally on climate change in world history in the streets of New York City.

China had already been on pace to curtail its coal use, as air pollution and concern over domestic effects of climate change have grown sharply in recent years. But to make its goals public in this manner is a major step forward. Wonkblog’s Matt O’Brien, at least, argues that China wouldn’t have made such a goal public if it didn’t think it could achieve it.

On its own, reaching these targets won’t be enough to stop all or even most of the irreversible effects of global warming, but early indications are they could be enough to at least rule out a worst-case scenario. In fact, climate scientist James Hansen has suggested that a bilateral U.S.-China announcement might be one of the only actions that could quickly bring about the kind of radical action on climate change required to eliminate the possibility of future climate disaster.

Though bold, China’s new goal of peaking emissions by 2030 is still probably a decade too late to avoid 2 degrees Celsius of warming. Scientists and politicians have agreed that it’s not “safe” to go above that 2 degrees Celsius benchmark.

By one estimate, if China adheres to this deal, it would advance the peak date of its carbon emissions by some 50 years, compared with a business-as-usual scenario, and could put the world on a path for warming of something like 2.5 degrees Celsius by 2100, as opposed to the hellish path to 4 degrees Celsius we’d been on. That’s a significant achievement. But these numbers also assume the rest of the world follows with targets at least as ambitious as China’s—and then follows through on them. As we’ve been painfully reminded over and over on climate, it’s easy to set targets and then not achieve them.

There are many questions remaining, not least of which are the specific actions the U.S. and China take on a domestic level to ensure the goals are met. The biggest looming challenge on the American side: The methods by which Obama plans to achieve this ambitious target will have to be contrived in defiance of a Republican-controlled Congress. As I’ve written previously, it’ll take more than just executive action to get the job done.