LAHORE, Pakistan—Could smartphones help increase the accountability of government workers and stamp out outbreaks of dengue fever? That’s the hope behind an innovative program developed by the state of Punjab in response to a record outbreak of the mosquito-borne disease in the wake of devastating monsoon rains in 2011.

Each year, more than 100 million people worldwide catch dengue fever, a viral disease that has also been dubbed “breakbone fever” for the excruciating joint and muscle pain it causes. And the threat is only increasing: “The global incidence of dengue has grown dramatically in recent decades,” according to the World Health Organization. Lahore—the capital of Punjab and Pakistan’s second largest city, with more than 9 million people—saw its first case in recent history in 2007. Following the 2011 flooding, the province as a whole, which is home to 120 million people, saw more than 21,000 confirmed dengue patients and 359 deaths. (Stats for the city of Lahore for 2011 year are not available, so it’s hard to get an apples-to-apples comparison.)

Meanwhile, mobile phone penetration in Pakistan is 74 percent today, up from 56 percent in 2007, making the country the fifth largest mobile phone market in Asia. And smartphone penetration there, while currently less than 20 percent, is expected to increase dramatically following the introduction of 3G networks to the country this year. The concurrent increases in dengue fever cases and mobile use created an opportunity for Pakistan to get in on a trend: Smartphones increasingly are being used across the developing world to collect data and improve health outcomes

In April, I visited the Lahore office of Dr. Umar Saif, the Cambridge-educated computer scientist who chairs the Punjab Information Technology Board. He told me that he helped develop the smartphone-driven program after the spike in cases in 2011.

To curb the epidemic during the 2012 rainy season, Saif and his team developed an app, loaded it onto more than 1,500 Android smartphones, and handed them out to fieldworkers across different government departments, instructing them to use the phones to upload geotagged photos of their mosquito mitigation efforts.

Fighting dengue is a constant battle and requires something of a puddle-by-puddle approach. The tedious jobs can be unpleasant, and corruption is rampant in Pakistan. To prove that they’ve done their duty, workers from a range of sectors have taken photos of unglamorous tasks like dumping out standing water accumulating at the bottom of a discarded tire, applying larvicide inside a clay pot near the Lahore Railway Station, and releasing tilapia, which have a taste for mosquito larvae, into local bodies of water. Government entomologists check standing water for Aedes aegypti mosquito larvae, the species of mosquito that acts as a vector for dengue fever. (Aedes larvae tend to be larger than that of of the Culex mosquito, which doesn’t carry dengue.)

The app helps ensure that people are out doing their jobs, not wiling away the afternoon in the teahouse. “The photos are GPS-tagged, and our servers timestamp the pictures as they come in, so it is difficult to forge, and we therefore verifiably know that the work is actually going on in the field,” Saif said. To date, workers have uploaded more than 680,000 photos through the app.

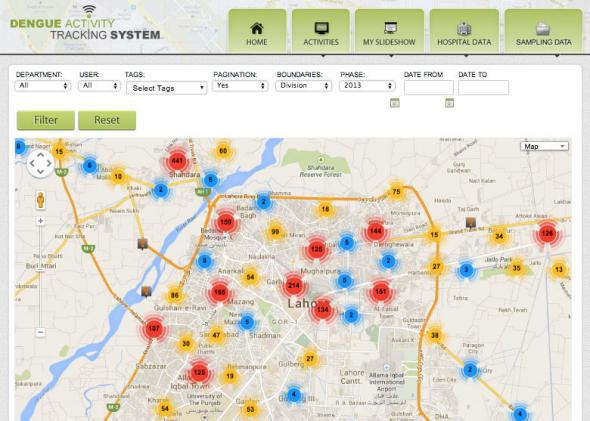

These photos are pinned to a map of Lahore, and the data about the presence of patients and larvae is analyzed by a system that generates outbreak warnings for specific areas.

The initiative has been largely successful: In 2012, after the smartphone program’s implementation, the number of deaths in Lahore dropped to zero, despite forecasts from public health workers that the year would see an even greater outbreak, given the predictions of a heavy monsoon season The results from 2013 were more mixed for the province as a whole, with 1,511 deaths reported in all of Punjab. But in Lahore, where the bulk of the prevention activities are concentrated, there were only 18 confirmed cases and eight deaths. The proof, of course, will be whether this progress can be sustained over time. The program will be tested again soon, as the monsoon season begins.

Saif says that the principles behind the dengue program could be applied to other spheres, and six months after its launch he rolled out a similar system to monitor agricultural workers. It helped officials learn that fieldworkers weren’t straying far from cultivated areas along the main roads, when farmers in more remote locations are the ones who most need assistance. Police in Lahore use a version of the app to take geotagged photos of crime scenes, and that crime data is analyzed and resources are deployed to hot spots. (A smartphone-based crime reporting system in Guatemala City was chronicled in the Atlantic last month.) The programs are creating a trove of data that Saif and his team can sift through in search of solutions. “There’s so much analysis that one could do based on this,” he said.

Now the Government of Punjab has 30 different applications using more than 13,000 smartphones. With an eye toward sharing this technology with others, in late May Saif rolled out Data Plug, a drag-and-drop Web interface to make Android data-collection applications that his team created in collaboration with the World Bank. “Mobile phones are our weapon of choice for monitoring government work,” Saif said.

Sonia Smith traveled to Pakistan on a fellowship sponsored by the East-West Center.