New York isn’t known for its hurricanes. At least, it never has been before. But after Irene in 2011 and Sandy in 2012, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo said he joked to President Obama that “we have a 100-year flood every two years now.” Is it possible that climate change has somehow turned the Big Apple—and the northeast in general—into a hurricane hotspot?

Possible, perhaps. But the atmospheric scientists I’ve talked to say it would be misguided to conclude based on those two storms that the northeast is becoming a common destination for tropical cyclones.

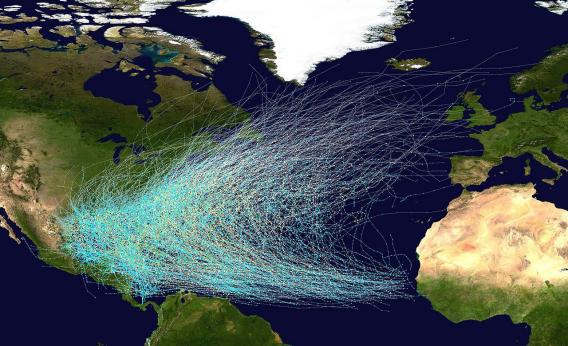

Typically the storms that roll up from the tropics toward the United States either make landfall somewhere in the Southeast—the Gulf Coast, Florida, and the Outer Banks are popular landing spots—or swerve on out into the North Atlantic. Occasionally they make it up to New England, where the Massachusetts coastline juts to the east. But it takes an unusual set of circumstances to create a direct hit on New Jersey or New York. And in the cases of Irene and Sandy, those were two quite different sets of unusual circumstances.

Irene made landfall in New Jersey and New York only after several other landfalls earlier in its journey, including one in the Outer Banks, and weakened over land along the way. Sandy, in contrast, stayed well offshore as it headed north, only veering toward land when it happened to interact with a winter storm that had been making its way east from the Rockies. (For a picture of how this happened, see my post on the Fujiwhara Effect.)

There’s little doubt that climate change played at least some role in the way that each storm evolved. Both drew energy from warmer-than-usual sea-surface temperatures. But climate-change models do not necessarily predict that more tropical storms will make landfall in New York in the future—nor in any other specific location, really, says Adam Sobel, an atmospheric scientist and professor at Columbia University.

“Every hurricane is a fluke, to some degree,” says Sobel. By that he means that any given storm’s path is determined more by the specific weather conditions at the time than by underlying climatic factors. While the connection between global warming and heat waves is relatively straightforward, the links between climate change and hurricanes are complex. Some climate models have predicted that warming should lead to fewer tropical storms overall, albeit with higher average intensities. But we don’t have nearly enough data yet to predict how specific regions will be affected.

In Sobel’s words, “Hurricanes are still rare events. That means that to see trends, you need to have enough of them to compute averages in a way that isn’t going to change with the next storm.”

Kevin Trenberth of the National Center for Atmospheric Research is among those who think climate change will make hurricanes more devastating, on the whole, partly because sea-level rise can lead to more severe storm surges (See his interview with Lisa Palmer in Slate for more.) But the fact that Sandy in particular made landfall in New Jersey is hard to pin on the climate, he adds. That said, he thinks it would be prudent for New Yorkers to prepare for more storms of this sort in the future—“not every year, maybe not even every 10 years,” but more than zero.