For nearly 60 years, George Orwell’s 1984 has been posing readers thorny questions about the dangers of ideology and the relationship between language, history, and memory. Robert Icke and Duncan Macmillan’s stage adaptation, which is now open on Broadway at the Hudson Theatre, adds another, equally pressing question: Why bother?

Icke and Macmillan’s version, which was first staged at London’s Almeida Theatre in 2014, opens with Winston Smith (Tom Sturridge) taking the fateful step of beginning a journal and then leaps promptly to some unspecific point in the future, where that journal is being dissected in what might be a graduate history seminiar. As Winston, who remains, semi-present, on the edge of the scene, watches, they discuss his book, which has become so famous that, one future character remarks, “It occupies a place in our collective unconscious, even if we’ve never read it.”

The way they talk about Winston’s book is familiar, and it’s meant to be. Like his chronicle of life in the fascist state of Oceania, Orwell’s 1984 is it’s easy to think you’ve read, even if you haven’t. But though its ideas, especially about the way totalitarian regimes use language to alter the landscape of thought, have become so common as to be almost banal, the book itself—as the hosts of Slate’s Culture Gabfest found when they (re)read it in March—is vaster and more complicated than the word “Orwellian” can encompass.

Still, as we languish in a country that shows many of the traits of a proto-fascist state, it’s fair to ask: Does that matter? Or, as one of the characters in the stage version asks, “How can you say a book has changed the world when the world is still exactly the same?” Is it enough to free your mind if your ass doesn’t, or can’t, follow?

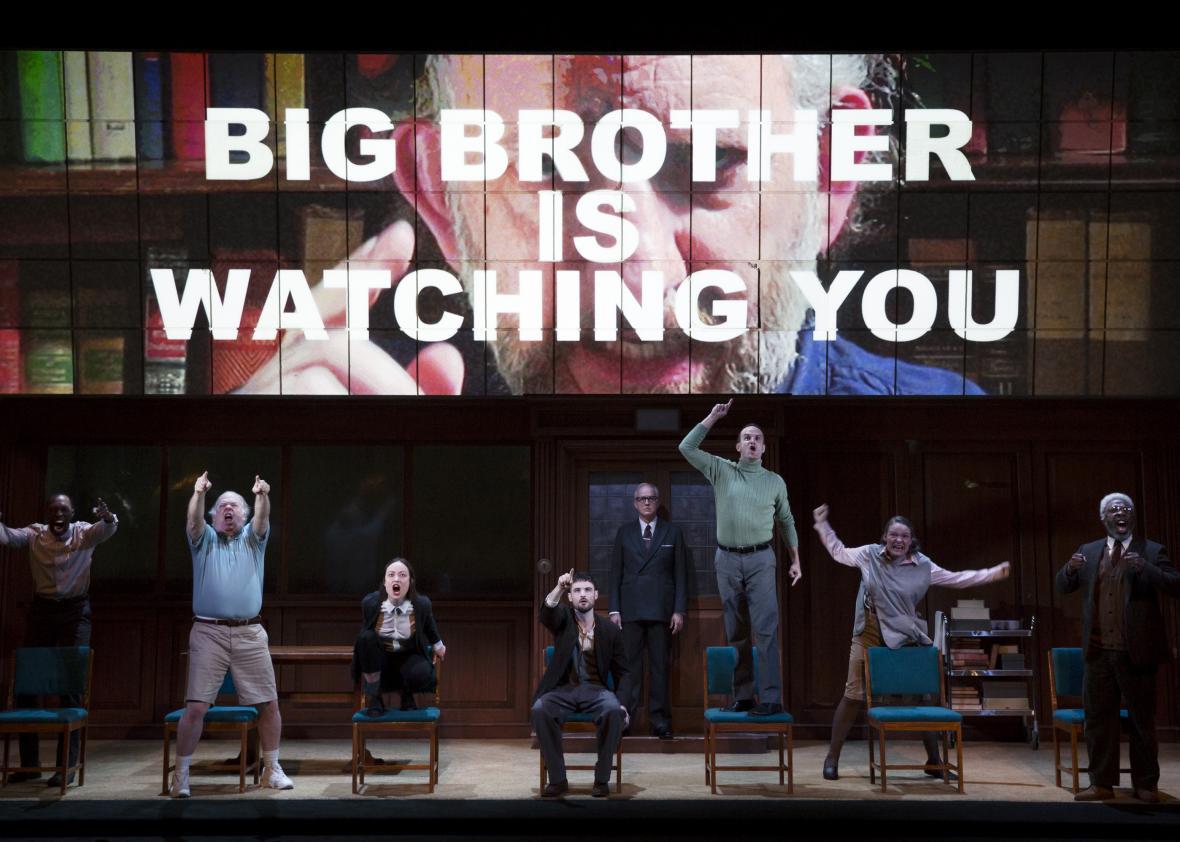

If we are indeed sliding towards totalitarianism, Icke and MacMillan’s 1984 is not about to go quietly. It’s a noisy production in both concept and execution, kitted out with video projections and surveillance cameras, shifting scenes with the flash of strobe lights and an ear-rattling slam. After four people reportedly fainted during previews, Olivia Wilde, who plays Julia, Winston’s partner in love and rebellion, tweeted, “Warning: this is not your grandma’s Broadway.” There is, naturally, no intermission, and a notice in the program informs you that if you leave your seat for any reason, there’s no getting back in.

The rationale for this periodic assault on the senses would seem to be Winston’s exclamation, “Is this what it feels like to go mad?” As we slip between frames—from Winston’s apartment, where he scribbles in a corner he thinks safe from the all-seeing telescreen; to an antiques shop where he sifts through artifacts of a past he has learned to say, and perhaps even believe, no longer exists; to the hidden, surveillance-free room off the shop, which the audience ironically glimpses only through hidden cameras and where he and Julia can act out for a few stolen moments the love their society forbids; and finally to the Ministry of Love, with its near-unimaginable tortures—it becomes impossible to keep track of what is real and what is imagined, what is history and what is myth. Reed Birney, who plays O’Brien, the party elder who may be a leader of the resistance or a cunning trickster out to ensnare would-be rebels, mostly deftly navigates the production’s levels of illusion and half-truth, so that we, like Winston, can never be sure if our minds are playing tricks on us. To those future scholars, the details of the world described in Winston’s journal are vague, lost in the mists of history or deliberately erased, but they’re confident of one thing: Winston Smith never really existed. So what, then, are we looking at?

There’s something a little, one should pardon the term, oppressive about the insistence with which 1984 jolts you out of your seat, and it’s not helped by the curious flatness of Sturridge’s performance. (Although the story’s setting in what was once London has not shifted, Sturridge has, like the production’s other English actors, been directed to speak in American accent, which seems to curtail his range somewhat.) But just as interrogation subjects wither beneath the lights, the play does smash through your defenses and eventually plants one square in the gut.

The audience’s job is to watch the play, but like Big Brother himself, 1984 is also watching you. Once Winston ends up in the notorious Room 101, the screams begin and the stage blood flows in extraordinary quantities. The production’s earlier scenes are lit in the dim glow of an underground bunker, but in the Ministry of Love’s torture chamber, everything is dazzling white on white; there’s nowhere to hide, for them or us. At one point, Winston calls out for help, and we’re meant to feel culpable: Aren’t we guilty, just like Oceania’s obedient citizens, of falling under the spell of our screens, of failing to look up as the world shifts around us? But here, too, we have a part to play; we know the ending has been written, and the script has no lines for us. Our place is to sit, and perhaps to feel bad, and then perhaps to congratulate ourselves for being so sensitive to Winston’s plight. But 1984 has one more curtain to pull back, one more question to ask, and it’s one that forms only after the lights have come up and the players have left the stage. What do you do next?