The death of Chuck Berry, one of rock ’n’ roll’s founding fathers, has brought a flood of well-deserved tributes and eulogies for the man who helped change the course of Western culture. But Charles Edward Anderson Berry wasn’t the only Chuck Berry trying to make his mark in show business in the 1950s. There was another Chuck Berry on the back roads of America in those days, dreaming the same crazy dream of delighting the world with his guitar licks and singing voice. But this Chuck Berry also wanted to delight the world with his unicycle. And his juggling. And his clarinet. And his roller skates. In retrospect, it’s probably best for all of us that only one Chuck Berry succeeded.

The Chuck Berry who failed, Charles Clifford Shepard Berry, was born in 1935 in Lawrence, Kansas. He was eight years younger than the legend who shared his name, but in a sense, he might as well have been born a century earlier, because he was one of the last people in the country who grew up in a vaudeville family. Like Buster Keaton, he started young, performing from the age of 4 as a member of “the Flying Berrys,” a roller skating act featuring Charles, his little sister Marion, and his parents, Charles Sr. and Elizabeth. During World War II, they toured the country with an act in which Charles, “the youngest pivot skater in the world,” performed high-speed tricks with his sister; when Charles’ youngest brother Ronnie was old enough, he was added to the act. The Berrys grew up on the road, an experience that made Charles a “perpetual wanderer,” as he told an interviewer in the 1970s. “I get a place two–three months, and I get buggy as hell. It doesn’t make any difference where it is, I just want to go.”

Des Moines Register

By 1953, Chuck Berry, now 18, was buggy as hell and ready to break out on his own. “The Berry youngest now has his own act,” Billboard reported, “doing Western dress type talk, juggling, and unicycle, but his ambition is to play guitar and sing hillbilly songs.” It was an ambition he pursued throughout the Flying Berrys’ touring schedule that spring and summer, as the family played the Catskills and the county fair circuit before heading back to the family farm in Lone Jack, Missouri, in time to harvest corn. A March 1953 ad for the Iowa Sports and Vacation Show on the state fair grounds promised 12 great acts, but it seems like it counted very generously: Audiences could see “The Six Boginos” performing their “foot balancing act” or “The Bogino Trio” performing “knock-about comedy,” and after they saw “the Five Flying Berrys,” there was a separate billing for “Chuck Berry: Unicycle and juggling.” It seems to have been his first solo listing, but from that point on, anywhere the Flying Berrys played, Chuck Berry had his own act.

Des Moines Register

The high-water mark of Chuck Berry’s solo career was also the year it collapsed: 1955. The Flying Berrys spent the spring and summer of 1954 at the Palace Theatre on Broadway, where they were booked with a magician named Jim Jimae. As it happened, Jimae’s son Gene was a successful recording artist who, in 1955, decided to use the proceeds from a concert tour to start his own label; Chuck Berry was one of the first artists he signed. It wasn’t as good a deal as it sounds: Gene was only 11 years old and had found success through novelty harmonica records. Nevertheless, Chuck—and presumably some other Berrys—cut a record for Gene’s new “Genie” label under the name “The Lone Jack Boys.” The A side was a song called “That Ugly Girl of Mine,” backed with “Australian Ho Down,” an instrumental. It’s not an easy recording to track down—while a dealer might have a copy, the digital world does not—but, according to Billboard, the boys “put on a humorous show with this novelty, and are personable enough, tho the material is slight.” But mediocre reviews or no, Chuck Berry was now a recording artist, and for a few glorious months, he was the best-selling Chuck Berry in the music industry.

In New York, the Lone Jack Boys were described as a hillbilly act, but when the family headed back to the Midwest for a gig at the Cat and Fiddle in Cincinnati, they were “A New York Revue … direct from the N.Y. Palace Theater on Broadway.” The newly sophisticated Chuck Berry emceed, juggled, rode his unicycle, and, like any recording artist, played his single. And for once in his life, listings for the show ran with a publicity photo of Chuck in a cowboy hat, strumming a guitar, with nary a roller skate or unicycle in sight. The Berrys celebrated the Fourth of July that year with a show in Stansberry, Missouri, where Chuck solidified his status as a solo act, playing to a crowd of 6,000 as “Chuck Berry, ‘The Lone Jack Kid.’ ” Other acts included “Tex Cashman, the Midland Empire Cowboy and his Wonder Horse, Judy,” and “Roy Newman’s Television Dog Act,” but even against that competition, the paper called Chuck the “highlight of the evening.”

Stanberry Headlight

It must have been around this time that Chuck Berry wished on a cursed monkey’s paw that his name would appear on record charts and concert venues all over the world, because before the end of the month, the other Chuck Berry released his first single, “Maybellene,” and everything came crashing down. By 1956, it had sold more than a million copies, and even with the endorsement of the Cincinnati Enquirer—which that January called the Flying Berrys “one of the ‘berry’ best shows” of the year—you couldn’t really put the name “Chuck Berry” on a marquee and bring out the Lone Jack Kid instead. By February of 1956, the Flying Berrys were billed as a foursome, and “Chuck Berry” had vanished from their playbill for good. Soon after that, he vanished from the Flying Berrys as well, joining the Army in 1957, then re-enlisting in 1961. Meanwhile, the remaining Flying Berrys seem to have made a push for his little brother Ronnie to break out, giving him a featured solo act. It didn’t take, although by now the group was booking gigs like the annual meeting of the Steuben County Rural Electric Membership Corporation in Angola, Indiana, which is less than ideal as a springboard to stardom. Throughout the 1960s, various incarnations of the Flying Berrys continued to perform at increasingly grim-sounding venues, eventually winding down with an appearance at the 1966 Greater New Mexico Sport Show in Albuquerque, where they were fourth on the bill, after an act called “The Acro-Nuts.” Judging from the promotional photo, only the Berry parents made it out for that last show. The Flying Berrys had gone the way of Chuck Berry, the Lone Jack Kid.

“Cliff Berry,” on the other hand, was out of the Army and still had a few more runs at the brass ring in him. Now going by his middle name, he and Ron put together a double act—music and comedy broken up with unicycling and juggling—and set off on their own as “The Berrys.” Eventually, they added Ron’s wife Nancy, Cliff’s wife, Patsy, and a non-Berry backup drummer, trumpeter, and trombonist named Dorothy Peterson. The Berrys finished out the decade towing two trailers and three kids (two of Cliff’s and one of Ron’s) cross-country. A family act once more, but not necessarily a happy one: Asked if life on the road with young children was stressful, Patsy told an interviewer in 1970, “We suffer greatly from depression.” She may have understood a little about what it was like for her husband to have started in show business under the name “Chuck Berry.” Her father had been half of a country music duo with Red Foley, though they split before Foley hit it big. His name was Bill Haley—but not, you know, that Bill Haley.

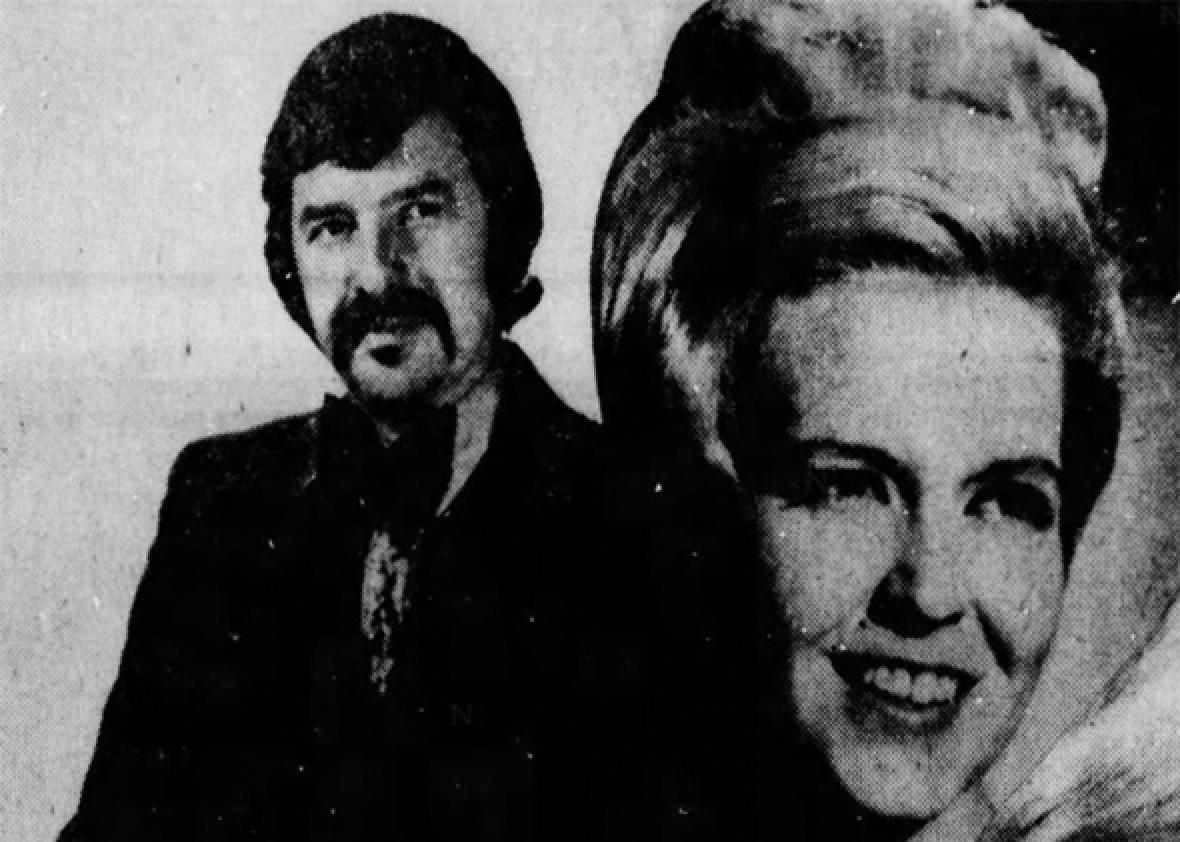

The dream, by the time of the Berrys, was turning the act into a kids’ TV show, but the dream never came true, and eventually everyone dropped out but Cliff and Patsy. In 1972, “Cliff Berry,” late of the Flying Berrys, late of the Lone Jack Boys, late of the Berrys, now working a day job as a flight instructor, was booked for a two-month residency—November and December, prime depression season—at “Jacque’s Old World,” the lounge at the Sheraton Airport Inn in St. Louis. Patsy accompanied him on electric organ; this time, they left the kids with their grandparents. A reviewer for the Post-Dispatch who got sent to their show wrote that Cliff, then 37, looked “like a refugee from a Spaghetti Western;” a promotional photo shows him sporting an incongruous combination of a ruffled tuxedo and a horseshoe moustache. The moustache was apparently convincing enough that, at the show the Post-Dispatch was at, an audience member demanded he play “Ghost Riders in the Sky.” (He didn’t know it but gamely faked his way through.) As usual, Berry’s act included interludes of unicycling and juggling, but if he performed “That Ugly Girl of Mine” for old times’ sake, it didn’t make the papers.

St. Louis Post-Dispatch

Those holiday gigs seem to have been Chuck Berry’s last stand as a professional musician. His career as a pilot didn’t fare much better: In 1978, he did seven months in a Colombian prison for drug-smuggling when an off-books Drug Enforcement Agency mission went awry. (Everybody claims to be on a secret mission for the government when they’re arrested with a plane full of weed, but Berry meant it; DEA agents really did send him to Colombia to buy marijuana in bulk, and he was eventually awarded $100,000 for his troubles after suing the federal government for abandoning him abroad.) He died in 2007 in St. Clair, Illinois, survived by children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. But it’s that last gig that lingers. The Sheraton Airport Inn where Berry spent the winter of 1972 was about a half-hour drive from the other Chuck Berry’s place in Wentzville, but if Chuck Berry, legendary rock ’n’ roller, ever hopped in his Cadillac and made the drive to see Chuck Berry, not-very-legendary vaudevillian, there’s no record of it. Spend your whole life trying to reach the promised land, and maybe some day you’ll get so close it’s a local call. That still doesn’t mean anybody’s gonna pick up.