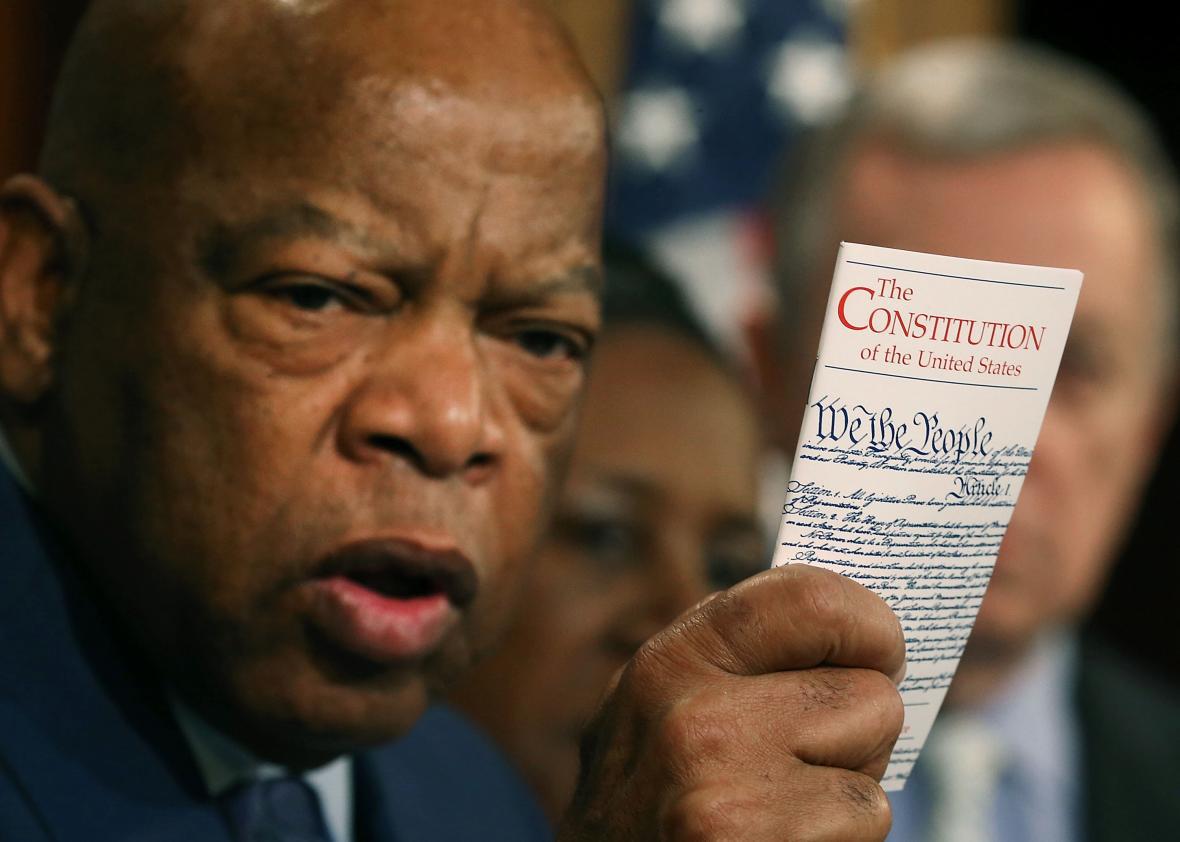

It’s particularly poignant that civil rights icon Rep. John Lewis kicked off his war of words with our soon-to-be tweeter in chief by announcing that he would skip Donald Trump’s inauguration. As Lewis’ recently completed trilogy of comic-book memoirs, March, makes clear, inaugurations hold a special place in his heart. The books, now collected in a boxed set by Top Shelf publications, interweave Lewis’ childhood and tenure in the civil rights movement with his experience watching Barack Obama be sworn in as the 44th president of the United States.

March, co-written with Lewis’ longtime aides Andrew Aydin and magnificently drawn by Nate Powell, elegantly evokes the feeling of Jan. 20, 2009, the sense that, by winning the highest office in the land, black Americans had reached the mountaintop; Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream was finally coming true. Book Two opens with the image of a black hand shaking a white hand as Rep. Maurice Hinchey greets Lewis at the House of Representatives, an image that will repeat at the end of Book Three as Lyndon B. Johnson shakes King’s hand.

A few panels later, Rep. Nita Lowey urges Lewis to hurry: “You should be near the front.” “There’s no need to hurry,” Lewis replies, as we transition to a panel that zooms far out to show the exterior of the Capitol and the grounds gathered outside. “I’ll end up where I need to be.”

I remember being suffused with this same feeling as I walked to the inauguration, seeing vendors with bootleg posters featuring King and Obama’s faces connected by a sunrise and the words I HAVE A DREAM in 60-point font. Obama then seemed more symbol than man, and that’s also how he inhabits March; despite his importance to the book’s overall structure, he makes only a few cameo appearances, and barely speaks. Instead, he inscribes a postcard to Lewis that reads, “Because of you, John,” and the two men embrace and cry.

As powerful as this moment is, it felt almost bafflingly out of step with the times when March’s first book was released in 2013. It was five years after the creation of the Tea Party and three years after the midterm shellacking that ground the government to a halt and revealed the limitations of Obama’s belief in compromise for its own sake. By the time the final volume came out in August 2016, we were so deep into a racist backlash against Obama that one party nominated a man whose major qualification was being America’s birther in chief.

It seemed particularly ironic that March’s civil rights narrative culminates with the signing of the Voting Rights Act—the same act that John Roberts’ Supreme Court gutted while Obama was president, enabling a wave of state-level bills designed to suppress the votes of black Americans under the bogus pretext of widespread voter fraud. During Obama’s presidency, it often seemed as if the Republican Party were torqueing the arc of history back toward injustice with all its might.

In reading March’s stirring stories of Lewis’ fights for civil rights, it’s hard not to think about President Obama’s veneration of the art of the compromise. From the never-actually-proposed public option, to the floating of a bipartisan “Grand Bargain” that would have gutted the social safety net and rewarded Republican intransigence, to his seeming to give up on getting Merrick Garland confirmed to the Supreme Court after a couple of press conferences, the character in March whom Obama most resembles isn’t Lewis but Lyndon Johnson. Johnson is often portrayed as the ultimate hard-driving ball-buster, but in March, we see a different side of LBJ, one who frequently urges leaders of the civil rights movement to slow down and be more reasonable because, as Lewis writes, he “felt our actions were making it harder for him to win votes in Congress.” It’s Johnson (along with the Kennedy brothers) who often needs to be pushed by activists into faster timetables, less accommodation, and less compromise.

As Lewis points out, “what’s so tragic” about Johnson’s accommodation of the forces of injustice is that it was ultimately self-defeating. “[LBJ] still won in a landslide,” Lewis writes, “and he lost the South.” Courting lost causes was a hallmark of Obama’s presidency, one that flowed from an optimism about the American character and our institutions—an optimism that both won him the presidency and was the source of many of his defeats.

Revisiting March a few days before Obama steps down, however, I found my frustration dissipating. March today is like looking a triple-exposed film, superimposing the reality of Obama’s presidency on top of the uplift of the inauguration, itself superimposed over the fight for integration and voting rights. The book’s hard-won hope—remember that word?—is now suffused with the dramatic irony of a Greek tragedy.

Obama was never going to remain a symbol forever, although he may become one again, now that his presidency is over. He was always going to be a compromising, and compromised, leader, but Obama’s pragmatism helped make him the most effective progressive president since Johnson. The forces aligned against him were immense, and, during the health care and recovery act fights, bipartisan. Someone like John Lewis, despite being a bona fide American hero, was never going to be president. A few months after March’s first book was released, he was arrested at a protest for comprehensive immigration reform.

Barack Obama, the greatest president of my life, is stepping down. In his place will stand a gilded ogre surrounded by a gaggle of Dick Tracy villains. Resisting, and then undoing, the damage of this election will be the work of the rest of our lives. But one thing March teaches us as it looks back is to keep looking forward and to remember that this work is not impossible. Look at everything that John Lewis did. Look at what he made possible. Look at all that changed during his life. Look at the violence he faced, the strategic gambits that could have gone awry, the conflicts within his own organization. Look how we can resist and how we can triumph.

In its final pages, March is careful to remind us that making our union more perfect—to borrow one of Obama’s favorite formulations—will not come without a cost. On the night of Obama’s inauguration, Lewis returns to his Washington, D.C., townhouse and discovers that he has 28 voicemails. One is from Ted Kennedy. “I was thinking of you,” he says. “I was thinking of you and Martin. I was thinking about the years of work, the bloodshed … the people who didn’t live to see this day.” Lewis puts his head in his hands and weeps. Reading it on a sleepless night, listening to my daughter dream uncomfortably through a baby monitor, I did the same.