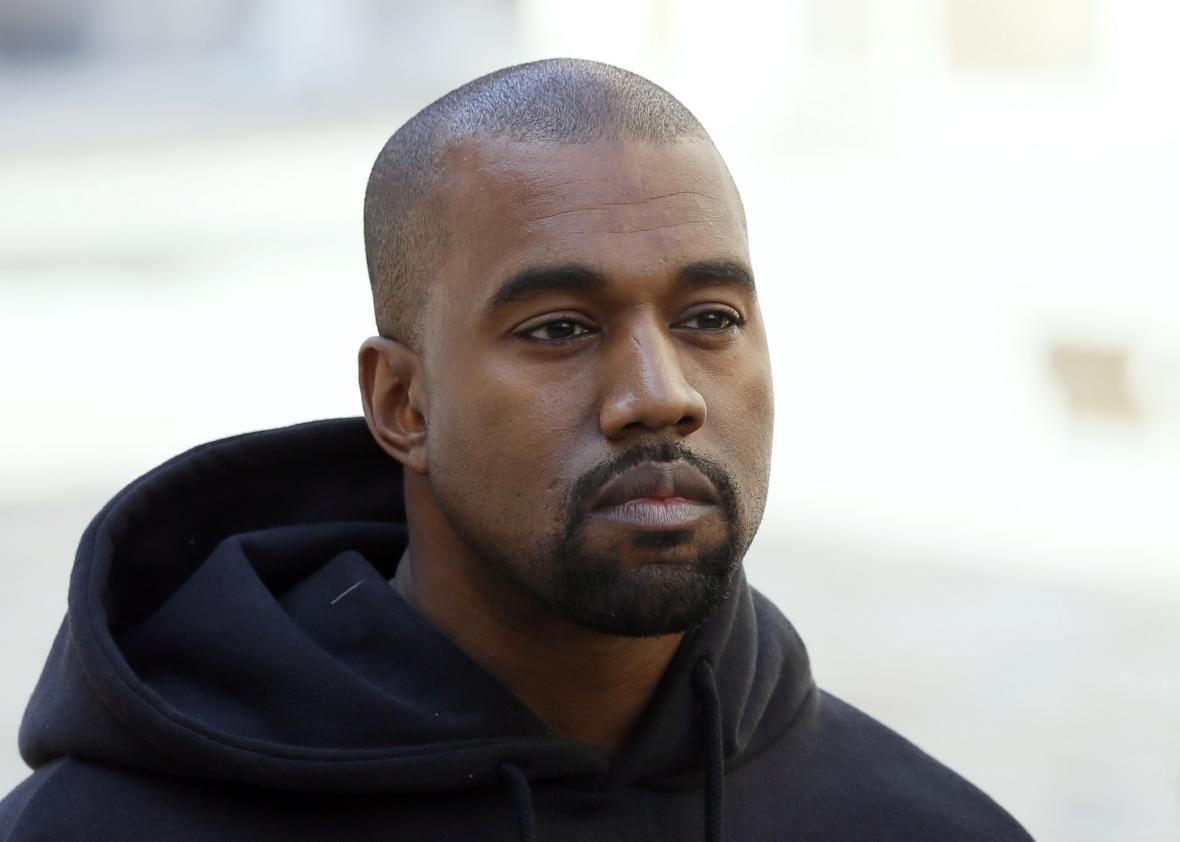

Who knew that Kanye West’s feelings about McDonald’s French fries were so complicated they could only be expressed in verse? Over the weekend, West published a poem in Frank Ocean’s zine Boys Don’t Cry, which came out in conjunction with Ocean’s new album, Blonde. The magazine is 360 pages long, flush with interviews and photography and poetry, but West’s stanzas are what push it to the edge of sanity. They are great, in their way. They go like this:

McDonalds Man McDonalds Man

The french fries had a plan

The french fries had a plan

The salad bar and the ketchup made a band

Cus the french fries had a plan

The french fries had a plan

McDonalds Man

McDonalds

I know them french fries have a plan

I know them french fries have a plan

The cheeseburger and the shakes formed a band

To overthrow the french fries plan

I always knew them french fries was evil man

Smelling all good and shit

I don’t trust no food that smells that good man

I don’t trust it

I just can’t

McDonalds Man

McDonalds Man

McDonalds, damn

Them french fries look good tho

I knew the Diet Coke was jealous of the fries

I knew the McNuggets was jealous of the fries

Even the McRib was jealous of the fries

I could see it through his artificial meat eyes

And he only be there some of the time

Everybody was jealous of them french fries

Except for that one special guy

That smooth apple pie

This is some artfully artless jibber-jabber, with irregular rhymes and no consistent meter I could figure out (despite a strong rhythm helped by repetition). The lines are end-stopped—no enjambment—so you don’t get the feeling of thoughts twisting, turning, or gathering steam (though in reading the piece aromatic steam is never far from your mind).

The speaker’s observations announce themselves in the same flatly gleaming monochrome as a McDonald’s logo. Few clauses, no real argument. Unlike the fries, this guy doesn’t appear to have a plan. But that declarative simplicity belies a frightening instability.

The speaker himself fails to show up as a character until the middle of the poem—why the secrecy, and then the egoistic interruption? This West mouthpiece is dealing in certainties: “I know” the French fries are planning something, he says, and “I knew” other menu items envied the fries. But how does he know? Did the taters tell him? That would be problematic, because the “evil” golden spuds smell too delicious to “trust.” We already suspect our speaker may not have the firmest grasp on reality. (Since when does McDonald’s have a “salad bar”?) Could it be that the speaker is, in fact, jealous of the fries and projecting that onto the McNuggets? And why is he constitutionally incapable of trusting something that smells good? (“I just can’t.”)

Toward the end, the speaker seems so bedeviled by his simultaneous attraction to and skepticism of the fries (they “look good tho,” he reminds us wistfully) that he loses the thread. He must retreat into Zen mantras: “McDonalds Man,” he mumbles, “McDonalds Man.” But is the speaker the same person or someone different entirely from this titular “McDonalds Man,” who in the body of the poem registers less as a mysterious entity than as an interjection: “McDonald’s, man”?

The real coup in this mystifying work of surrealist darkness is the ninth-inning entrance of its two most vivid and enigmatic characters. “Even” the McRib, who appears and disappears according to a logic the other foodstuffs cannot understand, covets the fries’ tempting fragrance, their plots. And he is a single Rib, separated from his fellows. The oven-crisped taters are a brotherhood. The McRib has presumably not been invited to conspire with the ketchup, the shakes, or the cheeseburger, despite his familial relationship with the third. And yet in a transcendental leap, the speaker is able to peer through the McRib’s artificial meat eyes, like Emerson through his transparent eyeball, and to perceive a deep, existential angst that transcends the food-human divide.

Then, the masterstroke. Like a dessert after the cognitive and sensory meal this elusive poem proffers, we have “that one special guy,” that “smooth apple pie.” He is the single item on the menu who does not envy the fries, who floats coolly above all the plotting and counterplotting of his fellow lunch options. This mysterious, debonair treat is the poem’s twist ending, heralding … well, we are not sure. But he resembles an important piece of West’s personal iconography—the “damn croissants” that will not be rushed. He gives those unflappable buttery pastries of 2013 an American spin, one infused with our native fruit, and with all of the hard-won experiential knowledge apples have suggested since the fall of man. In a universe of loneliness, ambition, and epistemological confusion, what precious truth, veiled to the rest of the fast food ecosystem, does this “special guy” know?

The poem won’t answer these questions. And yet a pale, speculative allegory emerges from McDonald’s’ bill of edible fare. You can be the conniving fries, West seems to say, or you can be the sad haters who want to be the fries, squinting out at them with your artificial eyes. (Fries, as potatoes, once had eyes, but no longer do. Their pandering to commercial tastes has corrupted their vision, perhaps.) The fries may smell good and have a lot of fans, but they aren’t the real thing.

Only a very few special guys can be the apple pies: self-possessed, secretive, genius. The apple pie is who the speaker ultimately wants to emulate, if he can shake off the hollow, glamorous value system of the fries. He yearns to, but those fries look good. McDonalds, damn.