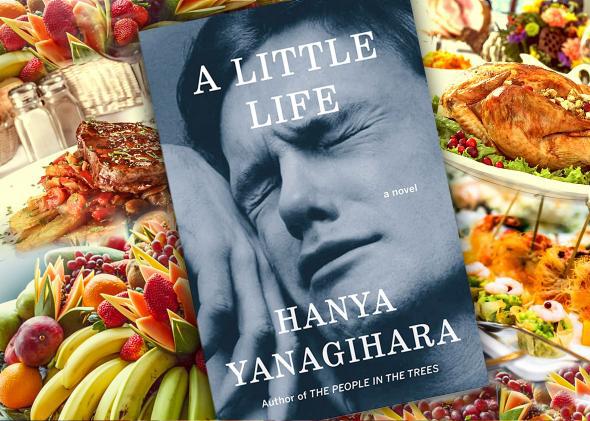

A Little Life, Hanya Yanagihara’s 720-page tale of indelible childhood trauma, is really sad, and everybody knows it. Yanagihara’s editor called the book a “miserabilist epic.” Jon Michaud, writing for the New Yorker, termed it “subversive” in its refusal to offer its characters redemption. The list goes on. Yanagihara has suggested that she meant for the book to be an illustration of when it might be appropriate to commit suicide. (She finds suspicious the conviction of psychotherapists that “life is always the answer,” as opposed to death.) I had to stop reading the book in public halfway through because I would start heaving and crying on the subway. But A Little Life is not all beatings and sexual abuse. Amid the darkness, sparkling somehow improbably like mica in concrete, there’s something seemingly brighter: a lot of mouthwatering descriptions of food.

There are the gougères Jude makes for a party at his apartment on Lispenard Street. There is sourdough bread and there are herbed shortbreads. There is walnut cake and persimmon cake and carrot cake and crab cakes. There are beautiful cookies. There are roasted figs served over ice cream and topped with honey. There is broiled halibut trout “stuffed with other stuff.” To drink we have limonata, water, prosecco, and iced tea. We have grilled corn with zucchini and tomatoes. We have poached eggs. We have ramps. (“I’m going to the farmers’ market to pick up those ramps.”)

Yanagihara has embraced interpretations that liken A Little Life to fairy tales. “I tried to meld the psychological specificity of a naturalistic contemporary novel,” she said in an interview, “with the suspended-time quality of a fable.” And the food in this novel is fairy tale food—illusory, tempting, deadly. It comes from the same universe as the witch-like women who loom over Jude at a party, as if he were “a child who had just been caught breaking a licorice-edged corner off their gingerbread house, and they were deciding whether to broil him with prunes or bake him with turnips.” It comes from the same universe as Jude’s first abuser, Brother Luke, who promises him an enchanted life in a fairy tale forest: “You’ll have the guest cottage, and every morning Buster will bring you your buckwheat waffles.” These promises are baked into Jude’s scarred skin, “stretched as glossy and taut as a roasted duck’s.” Like Brother Luke or the witch in Hansel and Gretel, A Little Life’s food descriptions dangle in front of us a delicious future—a happy ending—that it never planned to deliver in the first place.

Michaud at the New Yorker writes that the “most moving parts of A Little Life, are not its most brutal but its tenderest ones, moments when Jude receives kindness and support from his friends.” He goes further: “Who else but Tolstoy has made happiness really swing on the page?” he writes, quoting Martin Amis. His answer: “Yanagihara has.”

But I’d argue that the book’s great flaw is that it has a somewhat limited understanding of human happiness. This is why the abundance of food descriptions can be frustrating. The novel’s characters—even the ones who haven’t been traumatized in childhood—don’t experience happiness, but an accumulation of small, pleasurable moments that masquerade as happiness. They don’t have anything like principles (certainly no god) against which to measure their success in life. Instead, they have preferences.

The word “favorite” is used 31 times in A Little Life, distributed evenly throughout the book, once every twentysomething pages. Along with favorite foods, there are favorite projects and favorite people (i.e., friends). Jude, the protagonist, even has a favorite axiom. Every so often, to demonstrate that a character lives in a social context, Yanagihara will deploy a guest list full of names of characters who have not spoken a single line of dialogue. These are, we are to understand, the favorites, and we ought to be charmed by them, because the characters in this book are. The closest you can get to being happy in this world is to acquire your favorite things. This is a child’s understanding of happiness—the kind of illusions that would land you in a witch’s oven.

But the food in A Little Life is not all illusory and tempting and deadly. Consider Harold, Jude’s adoptive father. He’s among the book’s most believable voices, and one of his traits is “a tendency to make Thanksgiving more complicated than it needed to be.” Up until the end of the book, he always seems to fall short of his culinary ambitions, botching all the elaborate recipes he gamely attempts. But as Willem observes, Harold’s obsession isn’t really about the food—it’s about Jude. “It’s his way of telling you he cares about you enough to try to impress you,” says Willem, “without actually saying he cares about you.” This is a vision of cooking as caring, not as fairy tale temptation, and it is one of the few comforts of A Little Life. Though the promised feast—the cottage in the forest, the Thanksgiving dinner—may never materialize, at least Harold tries to make it real.