Steven Soderbergh’s new cable series The Knick, which premieres Friday on Cinemax, aims not so much to be a medical drama as to be a social panorama of New York in 1900. A fictional hospital, the Knickerbocker, led by its chief surgeon, John Thackery (Clive Owen), feels like both a beacon of turn-of-the-century progress and a shocking house of horror. There are three deaths within the first 10 minutes, yet it is an age of “endless possibilities,” Thackery informs us early on. “More has been learned about the treatment of the human body in the last five years than in the last five hundred.”

The show’s producers have emphasized their desire for historical authenticity and the great lengths taken to replicate surgical procedures with accuracy. Much of their staging came from consulting records in the Burns Archive, an impressive historical collection of photographs and medical history materials curated by Dr. Stanley Burns, a doctor who also served as medical adviser for the show. But the world of The Knick is better seen as an image of history refracted in a funhouse mirror than as an accurate snapshot of medical progress and society in 1900. What is accurate, and what is exaggerated on The Knick? I consulted several medical historians and papers to find out.

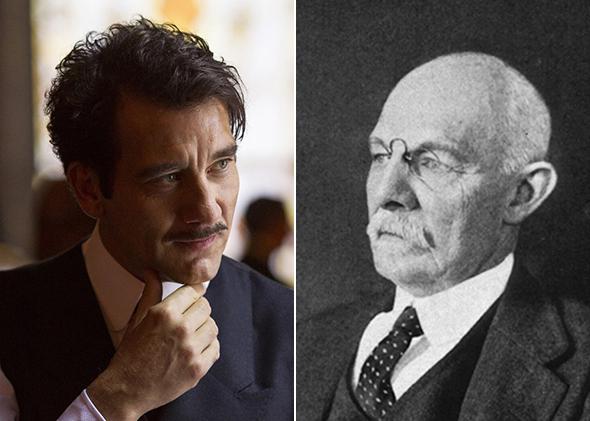

John Thackery (Clive Owen) and William Halsted

Photo (left) by Mary Cybulski/Anonymous Content (right) courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Owen has said that the show’s writers based the drug-guzzling John Thackery on William Halsted, one of the most important figures in modern surgery. Halsted is credited with performing the first emergency blood transfusion in the United States, and with revolutionizing the way surgery is taught and practiced as a meticulous, scientific discipline.* In 1889, he was a founding professor, along with three colleagues, of Johns Hopkins Hospital, where he headed the department of surgery. He did struggle, as Thackery does, with cocaine addiction—the result of experimenting with the drug as an anesthetic for surgery. Still, it’s unlikely he would have been impressed with the cavalier demeanor his fictional counterpart exhibits in the operating theatre. A reclusive, somber man, “Halsted subordinated technical brilliance and speed of dissection to a meticulous and safe, albeit sometimes slow, performance,” in surgery, says the Sabiston Textbook of Surgery. Halsted’s principles for surgery—which insist on gentle, careful technique—were developed in the 1890s and are still followed today.

Surgery at the turn of the century

Photo courtesy Mary Cybulski/Cinemax

By 1900, surgery had become more commonplace and acceptable than The Knick implies. In the first episode Thackery, reflecting on his beginning at the hospital, tells his predecessor: “You are legitimizing surgery, taking it out of the barbershops and into the future, and I want to be part of it.” In real-life 1900 New York, on the other hand, surgery in a top-flight hospital would probably have lost much of its old unsavory image as a practice of crude butchery. Between 1880 and 1890, approximately 100 new types of operations were conceived, made possible by progress in anesthetics and antisepsis discovered in the latter part of the 19th century. A later episode in which a man is taken to a drunken barber for an amputation seems implausibly anachronistic. Other small anachronisms seem to be included for dramatic effect. For example, the show depicts surgeons performing operations barehanded, rather than with rubber gloves, which Halsted and his colleagues began using in the late 1890s.

Hospitals at the turn of the century

The late 19th and early 20th century saw an incredible rise in the number of hospitals in the United States. Quality varied greatly, says Peter Kernahan, a medical historian at the University of Minnesota, as all that would be required was a house with some beds and funds to start one. A 1910 book written by a surgeon who had spent time at New York and Washington Heights hospitals, Medical Chaos and Crime, caused a sensation by purporting to document gross misconduct in hospitals—drunken night nurses, greedy superintendents, and incompetently trained surgeons. The money pinching and bribery depicted on The Knick might have occurred even at reputable hospitals.

The body trade

As greedy as some hospital workers may have been, a lurid black market cadaver trade could not have existed as it does on The Knick. (Not least because an early scene has a doctor declaring that “Other hospitals may frown on studying the dead, but I believe it is the only way to advance our knowledge of the living”: Human anatomical dissections date back to ancient Greece; doctors in 1900 would certainly have been doing them.) It’s true that cadavers would have been a commodity in demand, says Michel Anteby of Harvard Business School, and fresh ones were better for study than older, decaying ones. So one might think that an ambulance driver on the lookout for a business opportunity would be in a prime position to deliver (for a good fee) luckless patients who did not survive the journey to a hospital.

But Kernahan notes that it’s unlikely this happened in 1900 New York City: New York was one of the first states to pass “anatomical acts” in the mid-19th century, to discourage body snatching and the inappropriate sale of cadavers. Under such laws, only bodies left unclaimed by friends and loved ones could be used for medical studies. Beginning in the 1830s, these acts also helped provide anatomists with “a steady supply of free cadavers, … rescuing the profession from the taint of association with unsavory lower-class body snatchers,” writes Michael Sappol in A Traffic of Dead Bodies: Anatomy and Social Identity in Nineteenth Century America. For ambulance drivers in 1900, brokering a trade in cadavers would have been a dubious way to get rich (though, interestingly enough, there is a cadaver shortage today).

Black surgeons

Cinemax

For a hospital that is supposed to be on the cutting edge of surgical history, the Knick is a strangely conservative one with respect to many medical practices and attitudes. What’s truly (but anachronistically) progressive about the hospital is that it’s the first in New York to hire a black doctor. In real-life New York, this didn’t happen until 1920, with the appointment of Louis Wright at Harlem Hospital, on which occasion several hospital surgeons resigned in protest.

If Edwards has a historical model, it is likely Daniel Hale Williams, a pioneering cardiac surgeon, and founder of the first hospital with an integrated staff—Provident Hospital in Chicago—in 1891. In the real-life history of integration, it was a black doctor, not white benefactors, who led the charge.

Previously:

How Accurate Is Get on Up?

How Accurate Is Jersey Boys?

How Accurate Is Lone Survivor?

How Accurate Is The Wolf of Wolf Street?

How Accurate Is Captain Phillips?

How Accurate Is American Hustle?

How Accurate Is 12 Years a Slave?

Correction, August 8, 2014: This post originally misstated that William Halsted is credited with performing the first blood transfusion in the United States. He is credited with performing the first emergency blood transfusion.