The Monuments Men made $22 million over the weekend, good for second place, despite being been panned by most critics. (It currently holds a 32 percent “fresh” rating on Rotten Tomatoes; one critic found it so reprehensible he walked out.) Cinematic shortcomings aside, is the World War II action-comedy fairly faithful to the true story it’s based on, at least?

Not really, no. While it preserves key facts and big moments, the script by George Clooney and Grant Heslov takes major artistic license in its depictions of the mission. As historian Elizabeth Campbell Karlsgodt told me, “It’s accurate on a very basic level, with the idea that President Roosevelt charged these art experts, led by Americans, but also including other Western Allies … to protect cultural heritage” during the war.

Beyond that, there are a number of “distortions,” in Karlsgodt’s words, starting with the very setup for the mission. The initial task, Karlsgodt explains, was to protect historic buildings, not recover art. “They were initially going to try to provide lists so that Allied forces wouldn’t bomb historic sites, and once they were on the ground, then identifying damaged buildings and trying to carry out repairs when they could.”

Using the film’s original source material, The Monuments Men: Allied Heroes, Nazi Thieves, and the Greatest Hunt in History by Robert M. Edsel (with Bret Witter), as well as Karlsgodt’s expertise, I’ve sorted out fact and fiction in the film. Spoilers follow.

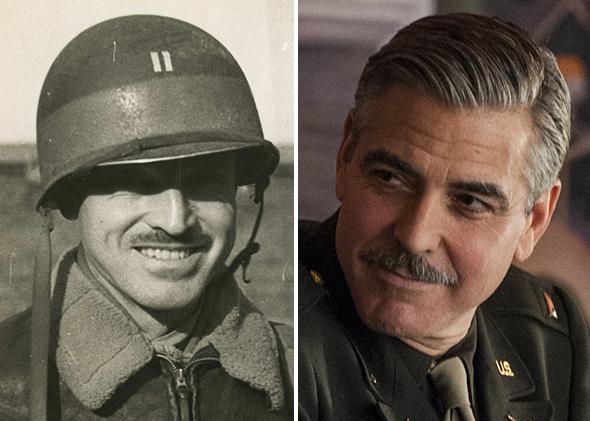

George L. Stout/Frank Stokes (George Clooney)

Photos courtesy Walter Hancock Collection, Columbia Pictures/20th Century Fox

Lieutenant Stout was a World War I veteran and art conservationist at Harvard. Along with Fogg Art Museum’s associate director Paul Sachs—who is not depicted in the movie—he was one of the earliest and most prominent advocates for protecting art during the war and he proposed the training of “special workmen” for conservation. After trying and failing to enlist museum leaders in a collective national conservation effort, Stout applied for active duty in the U.S. Navy in early 1943.

In the film, we first learn about the mission when Stokes, in late 1943, passionately makes his case to President Roosevelt (Michael Dalton) for the value of saving artwork from Nazi looters. But while The Monuments Men puts him at the center of the formation of what would become Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives (MFAA), in reality the subcommission was created without Stout’s direct input.

The Mission’s Beginnings

Meanwhile in Europe, British archaeologist and Lieutenant Colonel Sir Robert Eric Mortimer Wheeler grew concerned that what remained of Leptis Magna, an ancient Roman ruin in Libya, would be plundered and decimated in the midst of the war. Along with Lieutenant Colonel John Bryan Ward-Perkins, and with the support of a Civil Affairs Officer, Wheeler “rerouted traffic, photographed damage, posted guards, and organized repair efforts” at the site, as Edsel explains. (None of this is depicted in the movie.)

This inspired greater efforts once President Roosevelt and Winston Churchill agreed to invade Europe. One British and one American officer were sent to Sicily to inspect the monuments and territories “as soon as practical after occupation,” Edsel writes. American Captain Mason Hammond arrived first; with no supplies or support, he doubted the validity of the mission. “Even the first ‘Monuments Man’ … initially thought the manner in which the army was going about the mission was utterly foolish and a waste of time,” writes Edsel. The movie, on the other hand, portrays the officers as more or less undaunted by their task.

In September 1943, Sachs was appointed as a member of the Roberts Commission, which had a mission similar to what Stout originally proposed (with Supreme Court Justice Owen J. Roberts as chair). Sachs attributed the commission’s formation to Stout’s prior efforts, and he selected Stout to join the officer corps of the MFAA, an outfit the Commission decided to form.

James Rorimer/James Granger (Matt Damon)

Photos courtesy National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD; Columbia Pictures/20th Century Fox

Rorimer, who was drafted into the Army in 1943, was brought on to the mission by Sachs, his former professor at Harvard. Prior to his military stint, he helped expand the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s medieval collection. As a Monuments Man, he played a key role in helping to discover the Heilbronn mines that housed art from German museums. Karldsgodt, who has read his diaries, says he accomplished a great deal alone, with little support from the military. In one instance, Rorimer wanted to inspect the island commune of Mont Saint-Michel 100 miles away, and was given authorization by his superior officer—but was informed he’d have to walk. (The Monuments Men spent much of their time hitching rides and walking, some of which we see in the film.)

The Other Monuments Men

Most of the rest of the gang portrayed in the film are based on real-life people.

- Walter Garfield (John Goodman) is inspired by Walker Hancock, described by Edsel as a “renowned sculptor of monumental works.”

- Donald Jeffries (Hugh Bonneville) is based on Ronald Balfour, a British officer who, like his fictional doppelganger, was killed in the line of duty. Unlike Jeffries, Balfour was not trying to save the prized Madonna of Bruges statue on his own when this occurred, but was evacuating other artifacts, along with four German civilians, from a damaged church in Clèves, Germany.

- Richard Campbell (Bill Murray) resembles Robert Posey, a quiet, reserved architect who was relatively unknown within the art world prior to the mission.

- Preston Savitz (Bob Balaban) stands in for Lincoln Kirstein, who would go on to found the New York City Ballet.

- Sam Epstein (Dimitri Leonidas), the Jewish officer who fled Germany before the start of the war, is based upon Harry Ettlinger, one of the last surviving Monuments Men.

- Jean Claude Clermont (Jean Dujardin) doesn’t appear to have a real-life equivalent. Karlsgodt informs me that while American and French officers worked together in post-war Germany during the restitution process, there were no French officers who worked with the men who inspired the film’s other characters.*

The original assembly of assigned MFAA officers consisted of 11 men, seven Americans (including Hancock, Posey, Rorimer, and Stout), and four Brits, including Balfour. There were many more involved than are depicted in the film.

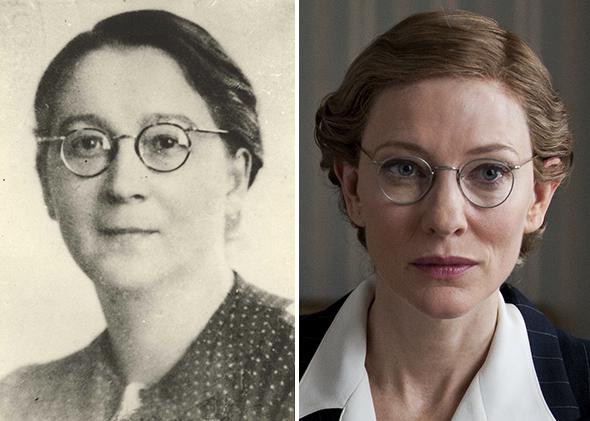

Rose Valland/Claire Simone (Cate Blanchett)

Photos courtesy Archives des Musées Nationaux, Columbia Pictures/20th Century Fox

Rose Valland, like her fictional counterpart Claire, was an employee at the Jeu de Paume Museum in Paris who secretly recorded the whereabouts of the artifacts stolen by the Nazis in France. She also had a close and crucial relationship with Rorimer, which resulted in a pivotal dinner meeting, where she finally shared her information on the Nazis after several months of working with him.

Unlike in the film, however, their relationship was strictly professional: “There’s no way there was romantic tension between them,” Karlsgodt tells me. “And I think it’s unfortunate because she risked her life to carry out that intelligence work, and also later became a captain in the French army, and played in the restitution process once all that art had been recovered.” While Valland’s story is becoming more well known, and she’s now considered a “wartime hero,” Karlsgodt doesn’t think the film does enough to honor her legacy.

Hitler’s Plans for the Art

According to Karlsgodt, the depiction of Hitler’s Nero Decree is “oversimplified.” The decree was issued on March 19, 1945 as an attempt to prevent Allied forces from using resources against the Reich during the war. In it, Hitler ordered that “all military, transportation, communications, industrial, and food supply facilities” be destroyed, but it didn’t explicitly include art. In the movie, however, when Stokes reads the decree aloud, he lists “archives and art” among the things set to be destroyed. This, Karlsgodt points out, “enables the plot to move forward,” so that our heroes are “racing against the Germans who are set now to destroy the art if Hitler can’t have it.”

In actuality, Hitler’s will specified that his art go to German museums, “strong evidence” that he didn’t want that art destroyed. Karlsgodt also finds it highly improbable that the Monuments Men even knew about the decree during their mission. “The systematic destruction [as seen in the film] being carried out as a result of the Nero Decree never happened,” she says. “Nazis destroyed art that they considered degenerate, like Cubist, Surrealist, Expressionist paintings, and we know that they burned several thousand—at least—paintings that they thought were actually toxic to the German spirit… [But] they didn’t destroy the art they valued.” (This included Germanic art, and the Ghent Altarpiece depicted in the film, which Hitler considered to be an example of “Aryan genius.”)

The Madonna of Bruges

Michelangelo’s Madonna of Bruges plays a pivotal part in the script, serving as the holy grail that the Monuments Men must reclaim in the memory of Jeffries, who dies trying to save it from Nazi capture. While it’s true that the statue (as well as the Ghent Altarpiece) would have been a priority for the mission, Karlsgodt feels that the film’s focus on those artifacts undermines the true significance of Hitler’s plans and their connection to the Holocaust. “It leaves out a really crucial aspect of this history,” she says. “Hitler saw it as a key way to seize the assets of Jews. He was not only eliminating Jewish influence, he was also getting their art.”

Though the Madonna was found in the Altaussee salt mine as it is in the film, the climactic race against the clock to excavate the art before the Soviets arrive to claim their territory is sped up for dramatic effect. As Edsel details in his book, the contents of the mine were recovered and recorded over the months of May and June 1945; when Allied-conquered territory was handed over to Soviet power, the crew had several days to carefully remove the most valuable pieces (including the Madonna and the discovered remaining panels of the Ghent Altarpiece) from the mine. Thanks to some disagreements over the deadline for relinquishing the territory, Stout and the other men at the scene had extra time, and were able to remove those pieces from the mine within a few days.

Thanks to Elizabeth Campbell Karlsgodt, author of Defending National Treasures: French Art and Heritage Under Vichy.

*Updated, Feb. 15, 2014: This sentence has been updated to clarify the French officers’ work with American Monuments Men.