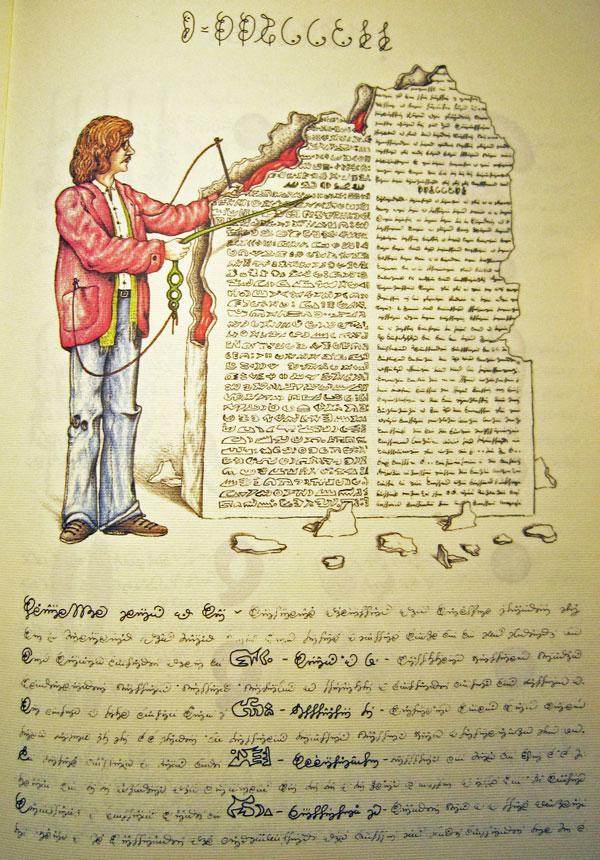

If you manage to lay your hands on a copy of Codex Seraphinianus and flip through its almost 400 pages of lavish illustration and handwritten commentary, the only words you will have any chance of understanding—depending on what sort of shape your Latin is in—are those on the title page. This is because the entire text of the book is written in an invented language, and alphabet, which nobody has ever been able to decipher.

And quite a few people have tried: the Codex has had a cult following since its original publication in Italy in 1981, and is often referred to as the world’s weirdest book. The book, which is the work of the Italian architect and designer Luigi Serafini (who is still with us, but has remained inflexibly committed to not explaining a damn thing about it), will be republished in a new edition by the art publisher Rizzoli later this month. It’s not the sort of thing that easily lends itself to classification, but probably the most accurate way to describe it would be as an encyclopedia of an invented alien civilization. It contains hundreds of carefully organized illustrations of plants, animals, people, machines, dwellings, cities, agricultural procedures, clothing, sexual practices, rituals, and so on.

It’s a lavish miscellany of weird specificity; because of its combination of absurdity and inscrutable precision, reading it is a feverish experience—although “reading” is exactly the wrong word, because that is an activity the book doesn’t permit. Rather, you simply look at it; you look at its diagrams of copulating couples gradually fusing together into crocodiles, at its drawings of egg-helmeted doctors rolling the flesh-pelts from supine bodies and trussing them up on hooks while detached skeletons observe, at its colorful bestiaries of impossible creatures (fish with brooms for tails, little snakes that double as shoelaces). And then you look at the accompanying text, with its lines and lines of beautiful and completely indecipherable script. And the experience is one of a book that makes perfect sense—that lays out an entire world in extensive empirical detail—but (crucially) not to you, because you don’t have the experience or the linguistic tools to understand it.

If you’ve read any Borges, you’ll probably find yourself thinking of his story “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius,” in which the narrator becomes obsessed with an encyclopedia of an obscure planet named Tlön, which turns out to be the invention of a bunch of intellectual pranksters, possibly including Bishop Berkeley. (An interesting essay on Codex Seraphinanius that appeared in The Believer a few years ago uses the Borgesian comparison as an entry-point.) You might also find yourself thinking of some of the bizarre creations of Clive Barker and, in particular, Guillermo del Toro. The Voynich Manuscript—a mysterious 15th-century volume handwritten in an unknown language and alphabet—often gets mentioned in discussions of the Codex, too, and is likely to have been an influence on Serafini. There’s also, unmistakably, a fungal whiff of ’70s psychedelia off the whole production, although its strangeness is much richer and more rigorous than that might suggest.

Up until fairly recently, Codex Seraphinianus had been very difficult to find, and signed copies of the first edition have sold for thousands. I’ve only read it—or failed to read it—in a PDF copy, which I found online and downloaded to my iPad’s Kindle app, which obviously is precisely the worst way to experience the book. (And what exactly constitutes rarity, by the way, now that almost any text can be found and obtained with a quick flurry of keys and a single click? Is it now more or less a synonym for expensiveness?) But even swiped and pinched and peered at through that high-res glaze, the Codex is still a disorienting and provocative vision of inscrutable otherness.