Last week, the Kepler spacecraft software detected an abnormal drift in the pointing of the observatory. As it was designed to do, the software sent the spacecraft into safe mode (putting the observatory to sleep, so to speak) and alerted engineers on the ground. When Kepler was restarted, Reaction Wheel 4 wouldn’t start back up. These wheels are needed to point the telescope; it needs three for normal operation. Reaction Wheel number 2 failed in 2012, so Kepler’s been running on that minimum of three for many months. With this new wheel problem, the mission itself is in danger.

It’s not clear how much danger, though. Once they initially found the wheel hadn’t restarted, engineers put full torque on its motor, but the wheel still wouldn’t move. In a press conference today, NASA said engineers are working on ways of possibly restarting the wheel, including trying to run it backwards, or starting and stopping it several times.

Even if the wheel doesn’t start back up, engineers think they can use the thrusters on board the spacecraft to help point it. That’s a pretty crude method and far from ideal, but may be possible to extend the mission.

I’m not willing to say the primary mission is over for sure, but this sounds pretty bad. With only two wheels, pointing won’t be as accurate. If they can get Reaction Wheel 4 back up, great! If not, well, we’ll see.

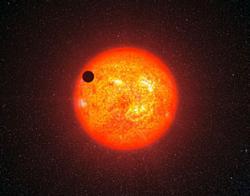

Artwork by ESO/L. Calçada

Kepler was launched in 2009, and its mission is to look for planets orbiting other stars. It does this by staring about 150,000 stars at the same time, and carefully measuring their brightness. If a planet orbits the star, and the orbit is lined up so the planet passes directly in front of the star from our view, it will block a tiny bit of the star’s light. This dip is usually at most only about 1 percent of the total light, and can be far smaller—it depends on the size of the star and the size of the planet—so this is painstaking work.

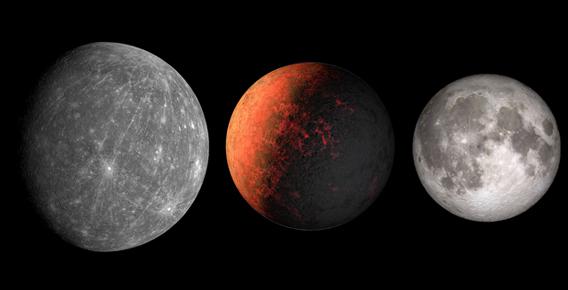

Despite that, Kepler data have revealed hundreds of planets, and there are thousands more candidates; potential planets that have been detected but not yet confirmed. Kepler’s found planets more massive than Jupiter, systems with more than one Earth-sized planet in them, and ones smaller than Mercury. It’s also found planets in the habitable zones of their stars. Not only that, but it has four years of data in its archives, so even if no more are ever taken, that’s a treasure trove of astronomical observations that will be studied for years to come.

Photo credits: Mercury: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Carnegie Institution of Washington; Kepler-37b art: NASA/JPL-Caltech/T. Pyle; Moon: NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center Scientific Visualization Studio; compiled by Phil Plait

It’s entirely possible the data already taken contain the faint signal of an Earth-sized, Earth-mass planet orbiting a star at the right distance for liquid water to exist on it. Such a signal can be very difficult to tease out, but just waiting to be found.

Also, NASA is planning the next generation of planet-finding mission: TESS, for the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, will consists of an array of four telescopes, sweeping a large area of the sky and examining more than 500,000 stars for planets. It’s scheduled for launch in 2017. In the meantime, there are several other observatories looking for exoplanets as well.

I’ll note that the Kepler mission was extended in 2012 after its primary run, and even if no more data are taken, it’s been by all counts wildly successful, increasing our knowledge hugely about planets orbiting other stars. While this potential loss of Kepler is cause for concern, it is by no means our last chance to search the Universe for other worlds. We’re just starting this exploration, and there are billions more planets out there to find.