Scanning the heavens, you might very well miss the star Kepler-62. It’s a rather typical star, slightly smaller, cooler, and more orange than the Sun, much like tens of billions of other stars in our galaxy. But it holds a surprise: It’s orbited by at least five planets… and two of them are Earth-sized and orbit the star in its habitable zone!

The two planets, called Kepler-62e and Kepler-62f, are both bigger than Earth, but not by much; they are 1.6 and 1.4 times the Earth’s diameter, respectively. Kepler-62e orbits the star every 122 days, while Kepler-62f, farther out, takes about 267 days.

Given the temperature and size of the parent star, this means that both planets are inside the zone around the star where water on the surface could be a liquid. Now, to be clear, this depends on a lot of factors we don’t know yet: the masses of the planets, their compositions, whether they have atmospheres or not, and what those putative atmospheres are made of. For example, Kepler-62e could have a thick CO2-laden blanket of air, making its surface temperature completely uninhabitable, like Venus.

Or it might not. We just don’t know yet, and won’t for quite some time—both planets are too small to get a measurement of their masses. It’s worth noting, though, that we do have size and mass determinations for a few planets like this around other stars, and they look rocky, like Earth. That makes it likelier these two planets are as well.

Also, the best computer models we have, based on what we know about how planets form and change over time, indicate that these planets could very well have water on them (it is, after all, incredibly common both in our solar system and in the Universe at large). We’ve already seen at least one planet with indications of the presence of water.

That’s pretty exciting. For years we didn’t know if any planets existed around other stars at all. When we started finding them all we could see were ones that were huge and hot, as unlike Earth as you can imagine. But as time went on, and our technology and techniques got better, we started finding smaller, less massive worlds. Now we are finding ones that look achingly like home.

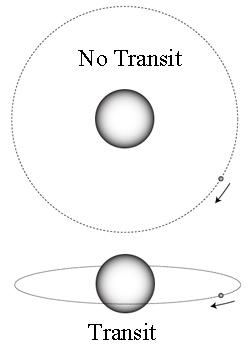

Adapted from a diagram by Greg Loughlin.

These planets were found using the transit method: The Kepler spacecraft stares at one region of the sky, observing about 150,000 stars all the time. If a planet orbits a star, and the orbit is oriented edge-on from our point of view, we see the planet pass directly in front of the star once per orbit. This is called a transit, and it blocks a teeny bit of the star’s light. The amount of light blocked depends on the size of the star (which we can determine) and the size of the planet. A big planet blocks more light, and a small one less.

That’s what makes finding Earth-sized planets hard; they only block about 0.01 percent of the star’s light. Kepler was designed to be sensitive enough to detect that meager dimming, though, and has actually found several planets in this size range now.

The other problem is timing. For a planet to be in the star’s habitable zone, it may take months or even years for it to pass in front of the star several times (multiple transits are needed to make sure we’re not seeing some other event, like a starspot). That takes time, but Kepler has been observing these stars for years now, which is why we’re seeing more and more smaller planets now.

And to find two orbiting the same star is very cool indeed. Assuming they’re made up of the same materials as Earth (metal and rock) and therefore have about the same density, you’d weigh 60 percent more on Kepler-62e, and 40 percent more on Kepler-62f. I’ll note that all things considered, neither would be paradise: Kepler-62e gets about 20 percent more sunlight than we do on Earth, and Kepler-62f gets about half; a bit hot and cold for my taste. But again, we don’t know the conditions on these planets. Give Kepler-62e a thin atmosphere, and Kepler-62f a thick one, and they might look a lot like Earth.

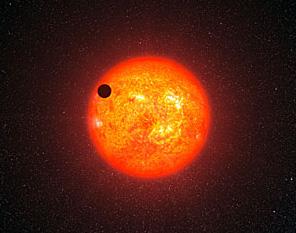

Image credit: ESO/L. Calçada

What an amazing thing that would be: two inhabitable worlds around one star (as opposed to all the Tatooines we’ve been finding)! It’s fun to imagine it being like a Victorian science fiction novel, spurring interplanetary travel and trade between alien races… or war. I guess that depends on which writer you read.

Of course, the habitability of these two newly-found planets is all supposition, but consider this: We think there are tens of billions of Earth-sized planets orbiting other stars. Even if a fraction of them are the right distance to be in their stars’ habitable zones, that still leaves tens or hundreds of millions of planets. That’s a lot of planets to play with. Sure, some will be too hot, too cold, have too much air or not enough, or have toxic atmospheres. But still, statistically speaking, it seems very likely indeed that there are plenty of planets out there that will look an awful lot like Earth.

I’m hopeful.

One of the reasons we look out into the Universe is to learn more about ourselves. Certainly, finding planets that are different than ours provides us with context, a there-but-for-the-grace-of-God-go-we sort of perspective. It also teaches us a lot about how planets form and evolve. Scientifically, different is good.

But we’re human, and we yearn to know if there are other worlds out there like ours. And if so, might life have arisen there as well? What a wonderful discovery that would be! And if not, it shows us how precious and rare life is.

Either way, knowing the answer—once we find it—will be extraordinary.