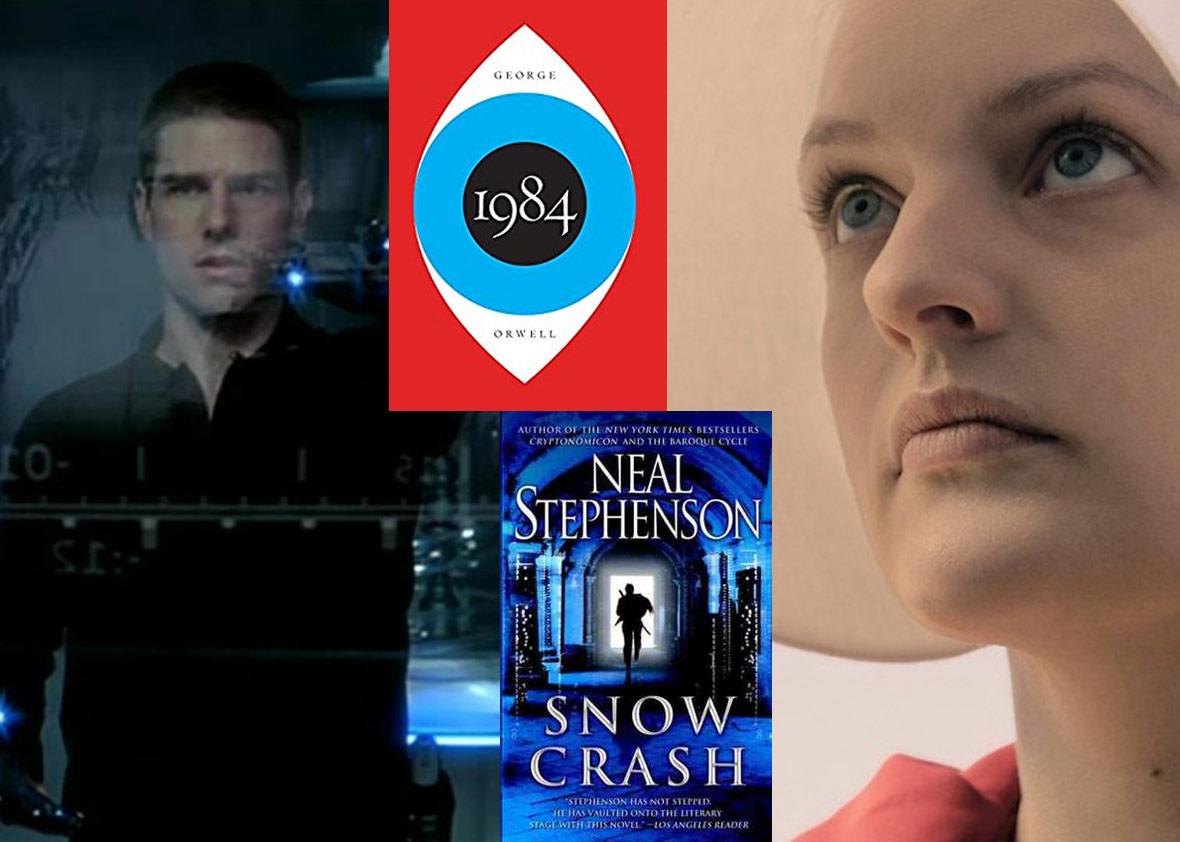

Consuming dystopian science fiction has quickly become a popular coping mechanism for Americans trying to adapt to (or resist) the sometimes-dark reality of 2017. Immediately after the Trump inauguration and the White House’s embrace of “alternative facts,” George Orwell’s 1984 shot to the very top of Amazon’s best-seller list. Other dystopian classics—like Aldous Huxley’s 1932 portrait of a more comfortable but no less frightening future authoritarian regime, Brave New World, and Sinclair Lewis’ alternate history of a fascist America, 1935’s It Can’t Happen Here—also quickly hit the top 20.

This same impulse has helped make a hit out of Hulu’s The Handmaid’s Tale, the first season of which is ending Wednesday. That show, based on the modern science-fiction novel of the same name by Margaret Atwood, depicts a near-future in which a totalitarian theocracy has overthrown the U.S. government, and the few women who are still fertile in the wake of an environmental crisis have been forced to serve as “handmaids” to bear children for the regime’s elites. The apocalyptic vision of the novel and the show have struck a chord among Americans wary of the new administration’s approach to gender politics, even making appearances at January’s Women’s March: “The Handmaid’s Tale is NOT an Instruction Manual!” read one sign; “Make Margaret Atwood Fiction Again!” read another.

The fact that so many people are turning toward these dire visions of the future may seem like cause for worry, but it is also a sign of hope. Great dystopian works like The Handmaid’s Tale and 1984, in the words of one defender of dystopian fiction, can serve as self-defeating prophecies helping us to recognize and prevent the dark worlds they depict. Put another way, The Handmaid’s Tale actually is an instruction manual, meant to teach us what we must fight to avoid. But hope can’t live on dystopia alone. It requires positive visions, too.

Thankfully, an ambitious new project launched this month aims to use the vision and expertise of the science fiction community—including Atwood herself—to move past dystopian visions. The newly announced Science Fiction Advisory Council, composed of a stellar selection of 64 bestselling sci-fi writers and visionary filmmakers, has tasked itself with imagining realistic, possible, positive futures that we might actually want to live in—and figuring out we can get from here to there. The council is sponsored by XPRIZE, the nonprofit foundation that uses competition to spur private development of things like a reusable suborbital spacecraft. The advisers on the council will “assist XPRIZE in the creation of digital ‘futures’ roadmaps across a variety of domains [and] identify the ideal catalysts, drivers and mechanisms—including potential XPRIZE competitions—to overcome grand challenges and achieve a preferred future state.”

This new project is reminiscent of Hieroglyph, a project from Arizona State University that is similarly aimed at leveraging science fiction to make positive change in the real world. (ASU is a partner with Slate and New America in Future Tense; I work for New America.) Like the Hieroglyph project, the Science Fiction Advisory Council will be launching with a short story collection. In July, XPRIZE plans to publish an online anthology of original science-fiction stories by members of the advisory council recounting the experiences of passengers on a fictional flight from Tokyo to San Francisco who are mysteriously transported 20 years into the future. (The air-travel theme makes a bit more sense when you realize that the project is cosponsored by Japanese airline ANA.) The stories, published at Seat14C.com, will presumably include visions of some of the “preferred future states” that XPRIZE seeks to identify, and will be followed by quarterly meetings of the advisers as they build out their roadmaps for avoiding dystopia and reaching those better futures.

If you’re surprised to hear that that science fiction might actually have a meaningful real world impact, you haven’t been paying attention. Science fiction and science reality have often found themselves in a feedback loop. Legendary sci-fi author Arthur C. Clarke came up with the idea of communications satellites in the ’40s. The less-famous sci-fi author John Brunner predicted computer worms in the ’70s. In the early ’80s cyberpunk classic Neuromancer, William Gibson coined the term cyberspace. Star Trek didn’t just motivate an immeasurable number of people to pursue engineering careers; it also sparked the invention of the first cellphone. The film WarGames spurred Congress to pass our first computer crime law. Through the years, sci-fi—like Steven Spielberg’s visually inventive adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s Minority Report—has also helped inform the latest innovations in user interface design.

Naturally, the tech titans who dominate Silicon Valley are also all sci-fi nerds who’ve been inspired by inventive authors’ visions of the future. Google’s Sergey Brin was inspired by the virtual reality envisioned in Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash; Peter Thiel and his PayPal co-founders were influenced by the cryptocurrency schemes of Stephenson’s Cryptonomicon; and Elon Musk—who recently hired a science-fiction movie costume designer to help create “badass” spacesuits for SpaceX—was motivated in his quest to make humanity into a multiplanetary species by a wide range of sci-fi, especially The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. Meanwhile, both Musk and Mark Zuckerberg have been reading sci-fi to help them think about the future of A.I. (Like those tech billionaires and countless other people, I was inspired to pursue my own career in tech by the science fiction I read when I was younger.)

It’s clear that science fiction, as it entertains, often also inspires. But the Science Fiction Advisory Council and its work is different. Rather than inspiration being a happy side effect of entertaining stories, the primary purpose of the SFAC is to use science fiction to directly inspire change in the real world—by prototyping our possible futures.

Beyond the natural feedback loop between reality and fiction, this new council of sci-fi advisers is emblematic of a different thread in the tie between science fiction and the real world: the deliberate use of science fiction as a tool for impacting, or predicting the impact, of real world tech and policy trends. Brian David Johnson, who was Intel’s in-house futurist for more than a decade and now spins future scenarios with the Army Cyber Institute at Arizona State University’s Threatcasting Lab, calls it “science fiction prototyping,” a term and tool that’s been adopted by some professional futurist consultants like those at Scifutures and by professors at MIT using sci-fi scenarios to teach tech ethics.

Science-fiction author Bruce Sterling calls it “design fiction”—the application of sci-fi to think about new design ideas through storytelling. At a broader level, sci-fi can be used as a tool for gaining “strategic foresight” through scenario building. Noted sci-fi authors like Madeline Ashby and Karl Schroeder even have masters degrees in “strategic foresight” and have built bustling futurist consulting careers in addition to their publishing careers, advising clients like the World Bank and Intel. Meanwhile, not just Intel but tech companies such as IBM, Microsoft, Google, and Apple also have in-house futurists. Nor is the trend limited to tech: For example, Scifutures counts companies as diverse as Hershey, Lowe’s, and Del Monte as clients.

This trend is not new, and not limited to the corporate context. The U.S. government has been consulting with science-fiction writers, and vice versa, for a long time. It’s unsurprising, for example, that there has been a tight feedback loop between real and imagined space exploration—illustrated especially well by this charming decades-old documentary about the making of 2001: A Space Odyssey that highlights Arthur C. Clarke’s close collaboration with NASA’s space program.

Perhaps more surprising, though, is that such collaboration between sci-fi writers and government has also extended to military and national security concerns. For example, right-wing sci-fi writers like Robert Heinlein and Jerry Pournelle were deeply involved in the conceptualization and popularization of ’80s-era “Star Wars” missile defense plans. Similarly, conservative sci-fi novelist Larry Niven and many other authors—organized via a futurist consulting organization called the SIGMA Forum, with the motto “Science Fiction in the National Interest”—were fixtures at homeland security conferences in Washington during the post–Sept. 11 Bush administration, according to news stories like these. As SIGMA’s founder, Arlan Andrews Sr., states on the forum’s website, “I formed SIGMA because I had heard more original and appropriate futurism on panels at any given science fiction convention than in all the forecasting meetings I ever attended while in D.C.”

The use of science-fiction prototyping in government hasn’t only been the domain of sci-fi’s sometimes-troubling right wing, however. The Obama administration was also into science fiction—especially Tom Kalil of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, who hosted a workshop with writers, artists, and scientists to envision the colonization of the solar system, sang the praises of design fiction as a tool for innovation, and even hosted a screening of Minority Report with Future Tense. The Obama OSTP even hosted a private meeting with a delegation of sci-fi writers who were visiting Washington for Future Tense’s Hieroglyph event.

The trend of science fiction being used as a prototyping tool is not new. What is new, however, is that so much sci-fi prototyping that used to be done in the privacy of the Pentagon or the corporate boardroom is now being done in public. Indeed, there’s been an absolute explosion of sci-fi prototype publishing in just the past few years. MIT Technology Review’s reporting has formed a foundation for its “Twelve Tomorrows” series of anthologies. Microsoft’s “Future Visions” anthology spins out the implications of the company’s latest research. When Brian David Johnson was at Intel, he launched the Tomorrow Project sci-fi prototyping story contest and related anthologies. Design software company Autodesk has published a set of stories generated by its strategic foresight division. The Institute for the Future has a collection of stories about “The Coming Age of Networked Matter,” while Scifutures has published a collection of science fiction that prototypes “The City of The Future.” Truly, there’s never been more corporate-driven tech scenario–building available to public.

There’s also been a similarly public explosion of sci-fi prototyping content around the future of the military, with both the Atlantic Council think tank and the U.S. Marine Corps launching contests to solicit stories as well as commissioning professionals to write short fiction. In 2015 we even saw the publication of arguably the first sci-fi prototype novel: Peter Singer, strategist at New America, and August Cole, who runs the Atlantic Council project, published the best-selling Ghost Fleet to game out what World War III might look like. Their one rule was that they could only write about technology that was already being designed today, with footnotes for every piece of tech in the novel. Their explicit goal, in addition to writing an entertaining book, was to educate and influence military thinkers—a goal at which they’ve succeeded.

Sci-fi prototyping has also moved beyond tech companies and the military. Journalists at Vice’s Motherboard have used science fiction to do a fact-based series of short stories about how a long-predicted major earthquake would impact Portland, Oregon. Fusion has used it to imagine the future of tech law, while lawyer Charles Duan at the copyright reform–focused NGO Public Knowledge has used science fiction to illuminate controversies in intellectual property law. Sci-fi prototyping to inform conference discussions has also become a trend. Human rights organization Access Now held a flash fiction contest at its conference on the future of encryption policy. (Another nerd disclosure: I wrote one of those stories.)

Mozilla commissioned stories from big-name writers like Cory Doctorow, Hannu Rajaniemi, and Daniel Suarez for its conference on the future of the open internet, while the Data and Society Research Institute similarly used science fiction as a scenarios tool for driving a conference discussion, which ultimately led to a published set of four stories about the future of A.I. and automation. A new online community and content portal called Scout is explicitly focused on using science fiction to understand the present and plan for tomorrow. And even Future Tense, where you’re reading this piece right now, has gotten into the game, publishing original science fiction by Emily St. John Mandel and Paulo Bacigalupi accompanied by expert commentary to help readers grapple with new technologies.

Will all of this science-fictional activity actually help us better cope with the future? Although it’s hard to tell, it seems that this flood of realistic near-term science fiction should at least help spur more, and more helpful, thinking about our own future than the fantastic tales of spaceships and aliens that have long dominated the sci-fi field. In the meantime, one new project at Glasgow University points toward a new and expanded approach to science fiction prototyping that looks to the past rather than the future. That project, Science Fiction and the Medical Humanities, is attempting to crowdsource a database that details past science-fiction’s treatment of medical technology to see what might be usefully applied to current medical thinking. In other words, rather than crafting new sci-fi prototypes, the project is looking to leverage the entire corpus of past science fiction as a prototype.

The wisdom of this approach is evident when you think of how it might apply in other areas, like A.I. ethics. As a society we are practically forced to use science-fiction concepts to conceptualize our artificially intelligent future, but those conversations seem mostly limited to our hopes for ethical artificial intelligence a la Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics, or our fears of evil A.I. like Skynet from The Terminator or HAL 9000 from 2001. Imagine if we instead systematically mined the decades of work on the issues of AI ethics done by thousands of talented science fiction writers, to widen our conceptual vocabulary?

Science fiction as a field has already done an enormous amount of hard thinking about the future of intelligent machines, and a range of other challenging topics. It’s simply up to us to use it. In the end, every science fiction is a prototype.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, follow us on Twitter and sign up for our weekly newsletter.