You know how some web addresses start with “https” and others begin “http?” That one letter makes a big difference. The “s” stands for secure, and it shows that your connection to the site is protected by encryption. That protection relies on a multibillion-dollar industry of institutions called certificate authorities whose job is to enable website encryption.

More than half the world’s web traffic is protected by an encryption system that relies on certificate authorities. You trust a certificate authority every time you load a secure site. The question is: Should you? Experts have warned that the system’s decades-old design makes it inherently vulnerable to breaches or even collapse.

In late March, Google announced that it no longer had confidence in one of the world’s largest certificate authorities, California-based Symantec. The company disputes Google’s claims, calling them “exaggerated and misleading.”

Google is in the middle of a years-long push to make certificate authorities more accountable, and thereby make the secure internet still more secure. Google has made compliance with a new plan called “Certificate Transparency” mandatory by October. These changes will almost certainly make website encryption more reliable, but they also show just how much power Google has to redesign the internet’s critical infrastructure on its own.

You could argue that certificate authorities exist today for one simple reason: People in the 1990s wanted to shop online. Back then, the makers of the first commercial web browser, Netscape, saw the internet’s potential as a shopping platform. It just had to make sure that customers’ credit card numbers wouldn’t be stolen in the process.

Basically, Netscape had to guard against two kinds of theft. A hacker’s first option is to watch the communication back and forth between your computer and a website until he sees a credit card number flash past. Netscape prevented this by encrypting that communication, making it impossible for hackers to read.

What if, however, the hacker redirects you to a dummy website that looks just like the real one? You might easily make an encrypted connection with the spoof website rather than the original and unsuspectingly enter your credit card number on the hacker’s site. Netscape had to invent a system that would tell customers which websites to trust.

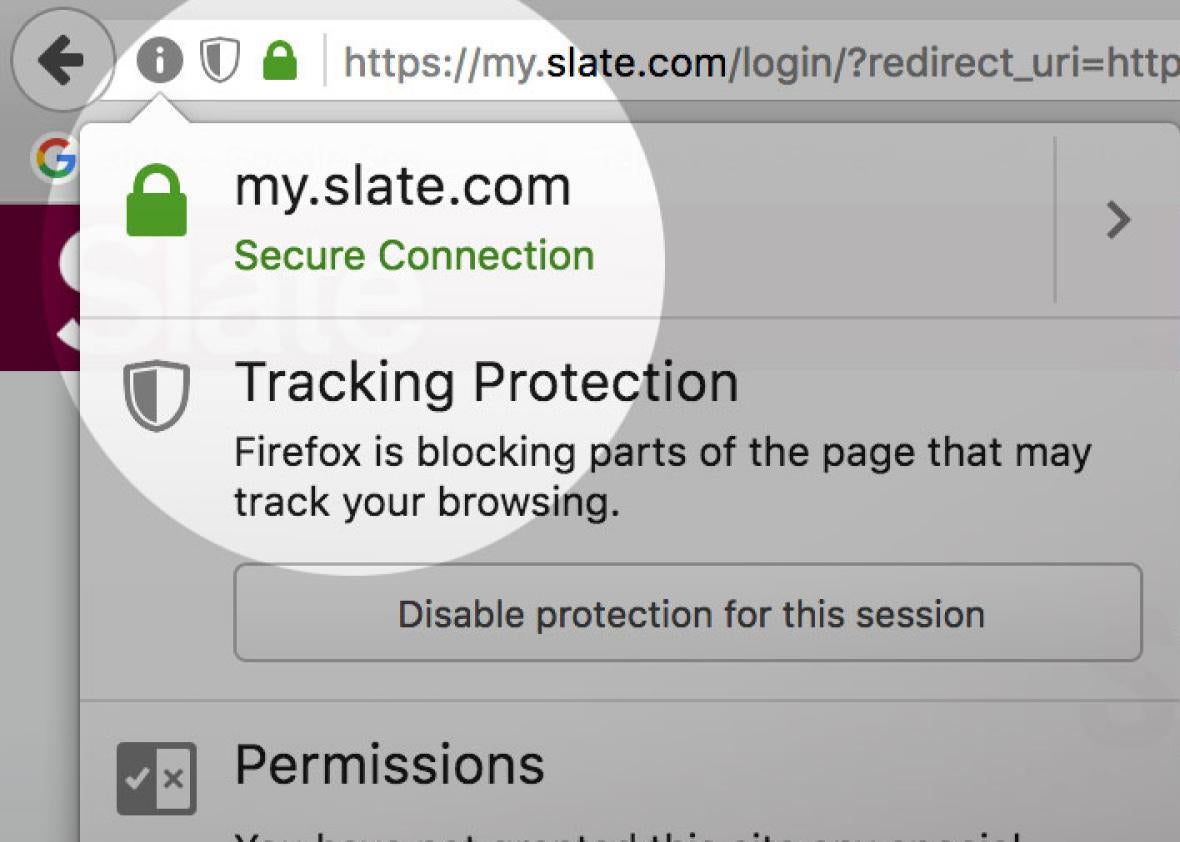

This is where “certificates” come in. Your browser won’t create an encrypted connection to a website unless the site can show a “certificate” signed by a trusted authority. A list of trusted certificate authorities comes programmed into your browser, which checks the certificate in fractions of a second every time you connect to an encrypted site.

You can think of certificates as digital passports. They prove the identity of websites. A certificate authority’s job is to make sure that it only gives a certificate to the real owner of a site. Google’s main complaint against Symantec is that it wasn’t doing this job well enough and allegedly vouched for 30,000 certificates without the proper checks. Symantec said there were only 127 unverified certificates and maintains that its certificate authority can be trusted.

Google has proposed that Symantec should re-issue all its certificates, which would be a huge inconvenience for Symantec customers. Last week, Symantec made a counterproposal. It offered a long list of measures to reassure Google, including extra independent audits.

Whatever resolution the two companies settle on will have to be carefully managed because the stakes here are pretty high. Symantec noted in its statement that “many of the largest financial services, critical infrastructure, retail and healthcare organizations in the world” rely on its certificates.

It’s not like every improper certificate is actually exploited by a hacker. Often there aren’t any practical consequences beyond having to replace the bad certificate. But in the rare cases when hackers can get a hold of fraudulent certificates, or if faith in a certificate authority collapses, the consequences can be dramatic.

This happened back in 2011 at a Dutch certificate authority called DigiNotar. (Josephine Wolff wrote a detailed piece for Future Tense about DigiNotar in 2016.) Iranian hackers broke into DigiNotar and issued fraudulent certificates for 46 sites, including Google. The hackers used the Google certificate to spy on about 300,000 Iranians’ Gmail accounts and steal their passwords.

DigiNotar’s business was providing certificates for the Dutch government, and the collateral damage from its collapse was a serious problem in the Netherlands. Government officials knew that DigiNotar could no longer be trusted. But should they revoke every DigiNotar certificate right away, which would disrupt all the sites using them, or allow time to get new certificates in place?

The choice is much like the one a government would face if it learned that another country was minting fake passports. If it rejects every passport from the rogue country, it will definitely catch the imposters—but will also hurt a lot of innocent people.

Ultimately, the interior minister had to go on TV and actually warn Dutch citizens to immediately stop using secure government websites while engineers rushed to replace the compromised certificates. Dutch citizens had to do without many online services for several days. Lawyers had to fax legal documents to the courts. The land survey organization couldn’t exchange information about the location of underground obstacles. Citizens couldn’t register car purchases online.

“In all of those cases ‘end users’ were affected,” said Erik de Jong, who worked in incident response for the Dutch government during the crisis. De Jong remembered being surprised to hear fellow passengers on the bus to work talking about DigiNotar. “Cyberattacks such as this don’t seem to concern most people until it happens to them,” he said.

Just before the DigiNotar attack, the same hacker briefly breached New Jersey–based Comodo Group, another of the world’s largest authorities. Peter Eckersley, chief computer scientist at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, wrote at the time that if Comodo had collapsed, it could have caused an “internet-wide security meltdown.”

It would have been like the situation Dutch officials faced after DigiNotar, except on a global scale: Either accept the economic consequences of disrupting millions of websites, or leave all those sites vulnerable to attack until they get new certificates.

In his annual report to the Senate Intelligence Committee on national security threats in 2012, then–Director of National Intelligence James Clapper wrote that the two hacks represented “a threat to one of the most fundamental technologies used to secure online communications.”

De Jong said that threat remains today. “The system is still very much as broken today as it was five years ago,” he said. Asked if a crisis like DigiNotar could happen again, he replied: “Absolutely.”

The DigiNotar hacker exploited the system’s fundamental flaw: that any authority can sign a certificate for any website. So the security of every encrypted site relies on the honesty and competence of the most dishonest and incompetent certificate authority in the world. At least several hundred organizations can issue certificates that most browsers will accept as trustworthy, including some in countries where the government might force them to enable surveillance.

Paul Kocher, a leading cryptographer who helped Netscape invent the system, told me that the economics of the modern certificate industry are bad for users’ security. Although a free nonprofit authority called Let’s Encrypt has gained ground recently, most authorities charge website owners for certificates. These certificate authorities offer such similar products that competition forces them to lower prices. This in turn compels authorities to operate cheaply, which can lead to shoddy security. One way authorities can make money is to offer services that others won’t—services that skirt industry rules, perhaps by enabling surveillance. Kocher said this doesn’t mean that all authorities misbehave, just that “the pressure for certificate authorities to behave badly are very, very great.”

Certificate authorities have been caught accidentally or deliberately issuing illicit certificates in at least a dozen cases since 2011. Chester Wisniewski, principal research scientist at Sophos Group, told me the system is “worthless” as a guarantee of security but said that, like any internet user, he still has to use it everyday.

A representative from the CA Security Council, an industry group, disagreed, saying that the fairly small number of problems in recent years shows that the authorities can be trusted. “I think the industry has really proven itself over and over again,” Jeremy Rowley, executive vice president at the Utah-based authority DigiCert, told me in a January interview. “To say it’s broken is kind of odd when DigiNotar was the largest issue that the industry’s had.” Rowley also noted that the industry has raised its security standards several times since 2011.

Whether or not users trust the industry, they have very little choice but to rely on it. It’s up to companies that make web browsers to decide which certificate authorities are reliable enough that their browser will accept their certificates. In practice, that means Google, Apple, Mozilla, and Microsoft—makers of the four most-popular browsers—have veto power on who can play in the certificate market.

In the past, Google and the other browser-makers have used that power with restraint. They’ve collaborated with certificate authorities to set industry standards and only punished authorities that broke the established rules. Google’s harsh statements against Symantec in March were an unprecedentedly public breach of the peace. Google had already strained the relationship by using its market power to force authorities into line behind its Certificate Transparency effort.

Starting in 2012, Google pushed Certificate Transparency through the internet standard-making process at the Internet Engineering Task Force. The task force focuses on the technical merits of new ideas, and it has no power to enforce new standards, relying instead on voluntary buy-in. In this case, however, Google has promised to punish those who don’t comply.

By October 2017, authorities will be required to enter each newly issued certificate into at least two public logs—creating a publicly accessible record of all trusted certificates. Anyone can set up a monitoring program, which will watch the logs for suspicious certificates.

While this won’t prevent problems at certificate authorities from happening, it should catch them much more quickly, as soon as people notice the first bad certificates. That should make any future breaches much easier to contain.

But what happens if some certificate authorities don’t comply with Google’s edict in time? None of the other browsers have backed Google’s threat to blacklist unlogged certificates. (All declined to answer questions.) If Google follows through on the threat come October, sites with noncompliant certificates will be flagged with certificate warnings in Chrome.

Most people routinely ignore these warnings, but they might spook and confuse users enough that they simply switch browsers—costing Chrome market share. Most major authorities are on board, however, which should minimize this problem. (Certificate warnings are most often caused by a technical or clerical error, not something sinister. Still, the safest decision is to avoid the site until it’s fixed. You definitely shouldn’t enter sensitive information on a site with a warning.)

Google’s push for Certificate Transparency raises another question: Why is it up to Google to decide how to reform the system that secures websites?

Greg Slepak, a California-based researcher, has vocally opposed Google’s plan. “No sane engineer would design it that way,” he said, noting Certificate Transparency’s baffling complexity. It might make sense, he said, if your goal is to make the certificate authority system more reliable. Slepak thinks that certificate authorities themselves are the problem and should be eliminated, but that Google isn’t willing to put them all out of business.

Google engineer Ben Laurie, the plan’s lead author, said that completely rebuilding the system is impractical. “I’m an engineer. I deal in actually solving real problems. You have to deal with where you’re at,” he said.

This past January, Google itself opened a top-level certificate authority called Google Trust Services. Although it won’t sell certificates commercially, this move does make Google the only company to control both a top-level certificate authority and a browser. That could be worrying since browsers have been the only effective check on certificate authorities’ behavior. So Google’s authority won’t have as much oversight.

Slepak retweeted a caustic anonymous online comment after the announcement: “Google has officially vertically integrated the internet.”

Other observers, like Chester Wisniewski, don’t see Google’s moves as so sinister. He thinks the company just wants to stop hackers from spying on their services, since Google itself has been the most common target for certificate authority hackers.

Even if Google has the best motives, its moves are still a troubling example of the company’s unchecked power. Certificate Transparency is probably the most important change to how we secure websites since Netscape introduced website encryption in the ’90s, and it has been carried out almost entirely on Google’s terms.

Certificate authorities went along with it because they have no choice. The other browsers have kept quiet. And government oversight isn’t even on the horizon. Melissa Hathaway, a consultant who held senior cyberpolicy positions under Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama, told me that even if they cared to act, any government’s power is limited in an international system.

There’s really no chance that consumers will ever know enough about these obscure systems to push Google one way or another. So for now, there’s little to stop the company from redesigning the internet’s critical infrastructure however it wants.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, follow us on Twitter and sign up for our weekly newsletter.