In 1776, John Adams wrote that a “representative assembly” should “be, in miniature, an exact portrait of the people at large. It should think, feel, reason, and act like them.”

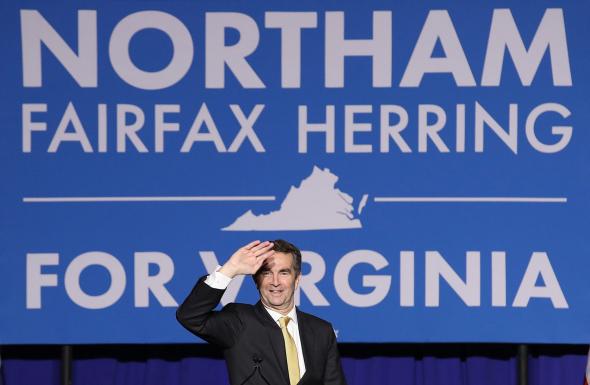

John Adams, meet Virginia. On Tuesday, the people made their thoughts and feelings abundantly clear. Democrat Ralph Northam crushed Republican Ed Gillespie by 9 percentage points to win the governorship, and Democrats also swamped the GOP in the state’s House of Delegates races, winning the aggregate vote in those contests by a similar 9-point margin. Most news outlets spun that House of Delegates margin as a Democratic triumph—a “tsunami election” that swept away what had been seen as an ironclad Republican majority. Yet pending a handful of recounts, Democrats seem poised to take just 50 of the chamber’s 100 seats. This 50–50 deadlock may prevent the party from securing the advances it campaigned on, particularly the state’s long-delayed expansion of Medicaid. Democrats rode an electoral wave to a legislative impasse. So much for Adams’ portrait of the people.

How might a party that wins a sizable majority of the popular vote fail to snag a legislative majority? Blame partisan gerrymandering. Virginia’s delegate districts were drawn in 2010, when Republicans controlled the governor’s mansion and the House of Delegates. Those districts were designed to entrench Republicans in power. Some commentators argued on Tuesday that the Democrats’ wins showed that progressives actually overstated the intractability of partisan redistricting. Business Insider’s Josh Barro summarized this reasoning, arguing: “You can beat the gerrymander without redrawing the map if you win at politics.” Liberal political strategist Tom Bonier went further, claiming that gerrymanders “rely on winning efficiently” and thus leave “more seats exposed to waves,” like the Democratic one we just saw sweep over Virginia.

Data and history suggest Barro and Bonier are badly mistaken. Democrats walloped Republicans at the polls, but the GOP gerrymander served as a red firewall, preventing the Democratic Party from translating its victory into an advantage in the General Assembly. Virginia’s gerrymander did not backfire on Republicans. It worked exactly as intended.

To understand the naivety of Barro’s position, consider the plight of Democrats in Wisconsin. Wisconsin Republicans engaged in a careful partisan gerrymander in 2010, identifying and sorting voters by political affiliation. (Discriminating against voters on the basis of political association raises grave First Amendment concerns, and the Supreme Court may soon curb the practice.) GOP mapmakers relied upon the time-honored strategy of “packing and cracking”—cramming most Democrats into a few dark-blue districts, then distributing the remainder through Republican-leaning districts.

In 2012, Democrats competed heavily in Wisconsin, driving up turnout with a strong ground game. President Barack Obama carried the state over Mitt Romney by nearly 7 points. But this triumph didn’t help Democrats win control of the state legislature. Across Wisconsin, Republican state legislators received 48.6 percent of the vote yet won 60 of 99 seats in the state assembly. Thanks to its gerrymander, the GOP had preserved a sizable legislative majority with the support of a minority of voters. Democrats won at politics. They won at the polls. They didn’t win the statehouse.

Gerrymandering apologists often dismiss this problem by blaming Democratic voters for clustering together in cities, creating a few dense liberal districts but allowing the rest of the state to fall into Republican hands. There are two problems with this theory. First, it doesn’t bear out in a politically diverse place like Wisconsin, in which a significant number of Democrats live in rural areas. Second, the Constitution requires that legislative districts within a state be of roughly equal population. Mapmakers cannot cram every city dweller into one district—1 million voters in progressive cities should hold just as many legislative seats as 1 million voters in the countryside. As the Supreme Court has explained, legislators “represent people, not trees or acres.”

It is true that Democrats’ habit (in some states) of living in dense urban corridors makes them sitting ducks for redistricting shenanigans. Cities are easy to gerrymander; partisan mapmakers can carve them up into warped districts that include a sliver of the city itself and a huge chunk of the surrounding region. Indeed, many of America’s most grotesquely gerrymandered districts use this trick. Consider, for example, Pennsylvania’s 7th Congressional District, known as “Goofy kicking Donald Duck,” which was drawn to dilute the votes of blacks in the Philadelphia area.

Republicans played this game in Northern Virginia, too, though perhaps not quite as well as they could have. Drawing straight from the gerrymander playbook, GOP mapmakers created a few Democratic “vote sinks,” blue districts into which they could pack Democrats. They then parceled out remaining Democrats in Republican-friendly districts. On Tuesday, Democratic candidates carried some of these districts—primarily the places in which conservative suburban residents had rebelled against Donald Trump. Had the maps been drawn equitably, more Democratic candidates would have prevailed. A map that transforms a 9-point Democratic majority into a 50–50 legislative draw is a map that was not drawn fairly.

What of Bonier’s claim that gerrymanders rely on efficient victories—that is, close margins that consistently favor one party—and are therefore susceptible to waves? Jordan Ellenberg, a math professor at the University of Wisconsin and Slate contributor, told me via email that this framing misunderstands how gerrymanders work. “An effective gerrymander doesn’t give you a bunch of seats you expect to win by 1 percent (too risky!),” Ellenberg wrote. “It gives you a bunch of seats you expect to win by substantially more.” As a result, the party that created the gerrymander should be able to maintain its majority by a narrow margin, even if it loses the popular vote—that is, unless that party totally collapses at the polls.

Virginia Republicans did collapse at the polls, but they still may not cede their legislative majority to Democrats. On Tuesday, their map stood strong when faced with a liberal landslide. There was still plenty of good news for progressives, though: By electing Northam, Democrats ensured they’ll have a seat at the table during 2020 redistricting, since the governor can veto the assembly’s maps. But until then, Democrats may languish just short of a legislative majority. The Virginia rout certainly serves as an important reminder that Democrats can still compete in individual gerrymandered districts. But it also illustrates the limits of a party’s success when the maps are rigged against it.