Tuesday’s arguments in Gill v. Whitford, a blockbuster challenge to partisan gerrymandering, raised a number of fascinating questions. Will Justice Neil Gorsuch ever learn how to properly season a steak? Can Justice Stephen Breyer survive a close brush with gobbledygook? Why does Justice Samuel Alito hate social scientists so much? And, most importantly, has Justice Anthony Kennedy finally settled on a test to determine when political gerrymanders cross a constitutional line?

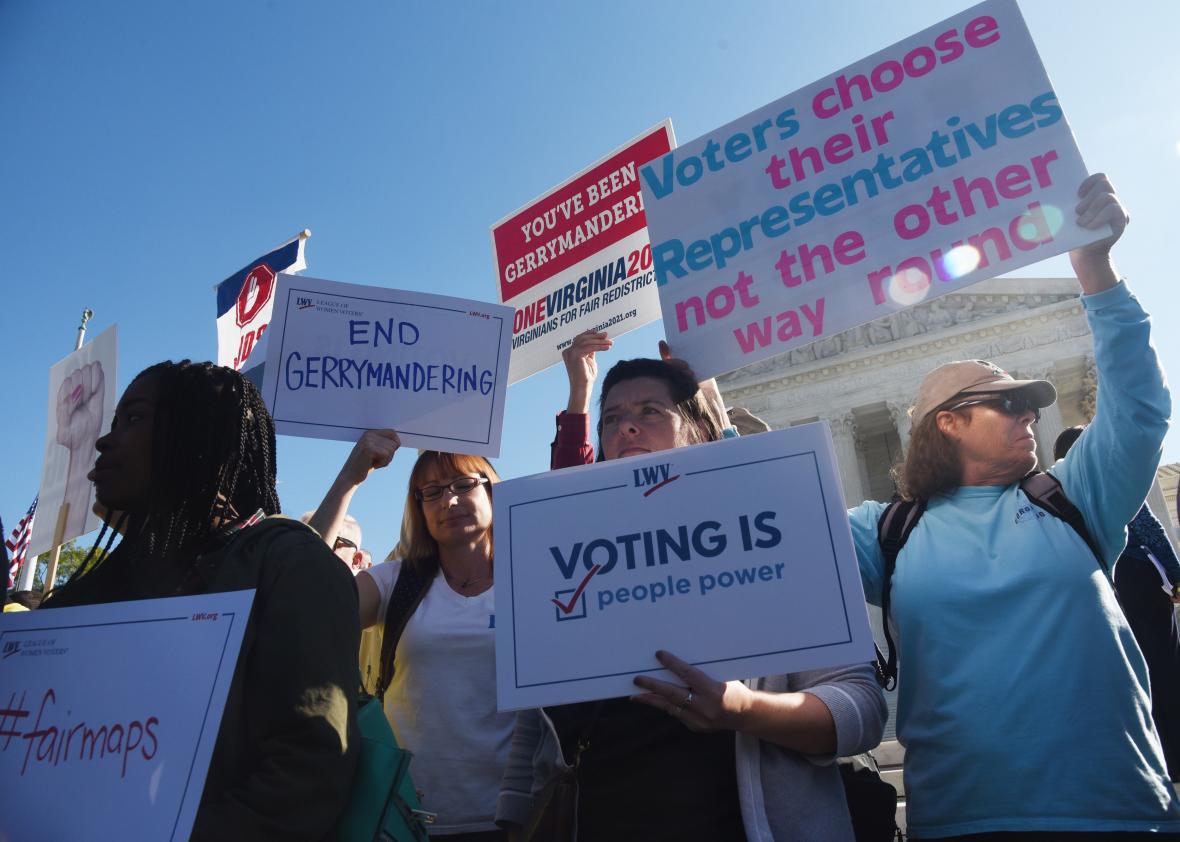

The answer to that last question—which will likely determine the outcome of Gill—wasn’t totally clear at the close of arguments. What was apparent, however, is that a majority of the Supreme Court is disgusted by hyperpartisan redistricting and eager to do something about it. That disgust may well be enough to strike down the most extreme gerrymanders. But it probably won’t persuade the court to usher in a golden age of democracy in which political redistricting is vanquished once and for all.

At bottom, Gill is a case about democracy and whether Kennedy will lend his vote to help save it (again). Partisan gerrymandering distorts democracy in a particularly pernicious way: When legislators draw maps that strongly favor their party, they create a majority that is both entrenched and endurable. Gill is a challenge to Wisconsin’s map, and the state provides an excellent example of this phenomenon. While drawing maps in 2010, Wisconsin Republicans engaged in “packing and cracking”—sticking most Democrats in a few safe Democratic districts and distributing the rest through safe Republican districts. This gerrymander has given Republican legislators a massive unearned advantage. In 2012, Republicans won 48.6 percent of the statewide vote—and 60 out of 99 seats in the Wisconsin state assembly. In 2014, they received 52 percent of the vote and won 63 seats. In 2016, they received the same percentage of the statewide vote, and their majority crept up to 64 seats.

Under this map, Democrats have no real hope of regaining a legislative majority in Wisconsin. A huge number of state elections aren’t even contested anymore; everybody knows the outcome in advance. And this isn’t a one-sided political question: In Maryland, Democrats have similarly gerrymandered Republicans out of power. Increasingly desperate voters have turned to the federal judiciary, imploring the courts to restore their right to cast meaningful votes.

The judicial holy grail for gerrymandering opponents is Kennedy’s concurrence in 2004’s Vieth v. Jubelirer. Kennedy wrote that truly excessive partisan gerrymanders may run afoul of the First Amendment. This makes good sense. Consider Wisconsin. When Republican legislators drew lines designed to diminish the power of Democrats’ votes, they were punishing these voters for associating with, or expressing their support for, the Democratic Party. This kind of viewpoint-based burden on freedom of expression and association would seem to run afoul of basic First Amendment principles. In Vieth, Kennedy explained that he was thus prepared to strike down a political gerrymander, but not until he was provided standards that are manageable and consistent.

Gill is an attempt to provide those standards. The plaintiffs offer several tests for the courts to use when gauging the reach of political redistricting, but they focus on two intuitive ideas: political symmetry and the “efficiency gap.” Political symmetry simply measures the equal ability of both parties to translate popular support into representation. The efficiency gap is a bit more complicated, but it basically asks whether election results are unusually lopsided—whether the victorious candidate wins by so many votes that her opponent never had a real shot.

Wisconsin Solicitor General Misha Tseytlin kicks off arguments by reminding the court that it has never invalidated a map on the basis of partisan gerrymandering. Kennedy promptly asks Tseytlin to respond to his First Amendment theory, and Tseytlin dodges—leading Chief Justice John Roberts to explain it for him. It’s “pretty straightforward,” Roberts says. “You, in your district, have a right of association, and you want to exercise that right of association with other people elsewhere in the state.” Tseytlin warns Roberts and Kennedy that, no matter how appealing that idea might be, it would “launch a redistricting revolution,” shifting the job of redistricting “from elected public officials to federal courts.”

Breyer isn’t so certain. “This is where I am at the moment,” he tells Tseytlin. “React to this as you wish. If you wish to say nothing, say nothing.” He then walks Tseytlin through the partisan symmetry and efficiency gap tests. “It’s not quite so complicated as the opposition makes it [seem],” Breyer concludes. These tests could, at least, detect “extreme outliers.” Why isn’t that manageable?

Tseytlin responds that these tests would force federal courts to engage “in battles of the hypothetical experts” using a “conjectural, hypothetical state of affairs inquiry.” Justice Elena Kagan responds that “legislators are able to [draw gerrymandered maps] pretty easily,” using “extremely sophisticated” techniques to entrench their majority. “This is not some hypothetical airy-fairy, we guess, and then we guess again,” she says. “I mean, this is pretty scientific by this point.” In short: Legislators are using gerrymandering technology for evil. Why can’t courts use it for good?

Erin E. Murphy then takes over for Tseytlin at the lectern. She represents the Wisconsin State Senate, where the Republican majority would very much like to stay in power. Kennedy promptly grills Murphy with a sharp hypothetical: Imagine a law that compels legislators to draw maps that consider “traditional principles” but must maximally favor one party. Would that be constitutional? And under what principle? Murphy ducks the query for several minutes before an irked Kennedy eventually intones: “I’d like an answer to the question.”

Murphy admits that such a law might constitute “a First Amendment violation in the sense that it is viewpoint discrimination.” It’s an odd moment, since she is effectively telling the justices that, yes, her client violated the Constitution, but, no, the court can’t do anything about it. Justice Sonia Sotomayor seizes the moment to ask Murphy “what the value is to democracy from political gerrymandering.” Murphy provides a gloriously nonsensical answer, asserting that “it produces values in terms of accountability that are valuable so that the people understand who isn’t and who is in power.”

“I really don’t understand what that means,” Sotomayor deadpans. The liberal justices have eaten Murphy’s lunch, and she slinks off.

Renowned Supreme Court litigator Paul Smith is next up, and the conservative justices are keen to slap him right back down. Roberts promptly dismisses partisan symmetry and the efficiency gap as “sociological gobbledygook.” Alito agrees, delivering an acerbic monologue about the alleged inconsistency of social scientists. (“Was there a question there, your honor?” Smith responds.) Breyer tries to help, acknowledging that the math behind these proposed standards might be “pretty good gobbledygook,” but that the underlying idea is pretty logical. Gorsuch then jumps in to criticize Smith for proposing multiple tests rather than sticking to just one.

“It reminds me a little bit of my steak rub,” Gorsuch says. “I like some turmeric, I like a few other little ingredients, but I’m not going to tell you how much of each. And so what’s this court supposed to do—a pinch of this, a pinch of that?”

Gorsuch soon reveals his contempt for this entire endeavor. “Maybe we can just for a second talk about that arcane matter, the Constitution,” he quips, then asks skeptically: “Where exactly do we get authority to revise state legislative lines?”

This question is somewhat startling, since even Justice Clarence Thomas believes that courts must invalidate redistricting plans that run afoul of a constitutional command. Gorsuch is apparently staking out a position on gerrymandering that’s so far to the right that he’s liable to teeter off the side of the bench.

Gorsuch’s vote might not matter much here, though, because Kennedy does not ask Smith a single question—a notable silence following his grilling of Wisconsin’s attorneys. It’s always tough to guess what’s going on inside Kennedy’s head, but the justice seemed disturbed by Wisconsin’s anti-democratic arguments and content with Smith’s answer to his request for standards in Vieth. For Kennedy, the First Amendment is the keystone of self-governance—and partisan gerrymandering is a frontal assault on voters’ right to freedom of association and expression.

The justice has too much respect for states’ rights to let courts meddle with minor gerrymanders. As he explained in Vieth, courts should only intervene when “legislative restraint” has been totally “abandoned,” resulting in grievous harm to “the democratic process.” Kennedy doesn’t want a redistricting revolution; he just wants a way for courts to sniff out extreme, entrenched political gerrymandering. With Gill, Smith might have given him the tools he needs to do precisely that.