On May 17, 1973, the Senate Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities investigating Watergate began 37 days of televised hearings featuring 33 witnesses. By then, the Washington Post had already run many of Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward’s biggest scoops on the scandal. Two aides to president Richard Nixon, G. Gordon Liddy and James W. McCord Jr., had been convicted of conspiracy, burglary, and wiretapping. Nixon’s attorney general, Richard Kleindienst, and his closest senior staffers, H.R. Haldeman and John Ehrlichman, had resigned. In June 1973, John Dean, Nixon’s former White House counsel, told investigators that he’d had at least 35 conversations with the president about the Watergate cover-up. In July, the country learned about the secret recording system in the White House, but Nixon refused to turn the tapes over to investigators.

In retrospect, it might seem like doubts about the scope of the scandal had been resolved by August 1973 when the hearings concluded. Yet according to the 1983 book The Battle for Public Opinion: The President, the Press, and the Polls During Watergate, a Harris poll found that 50 percent of respondents believed the media was giving Watergate “more attention than it deserved.” Another poll found that only 20 percent of Americans considered “Watergate, lack of confidence in government, or problems of Nixon and his administration” to be the most important problems facing the country. Most people were more concerned about inflation.

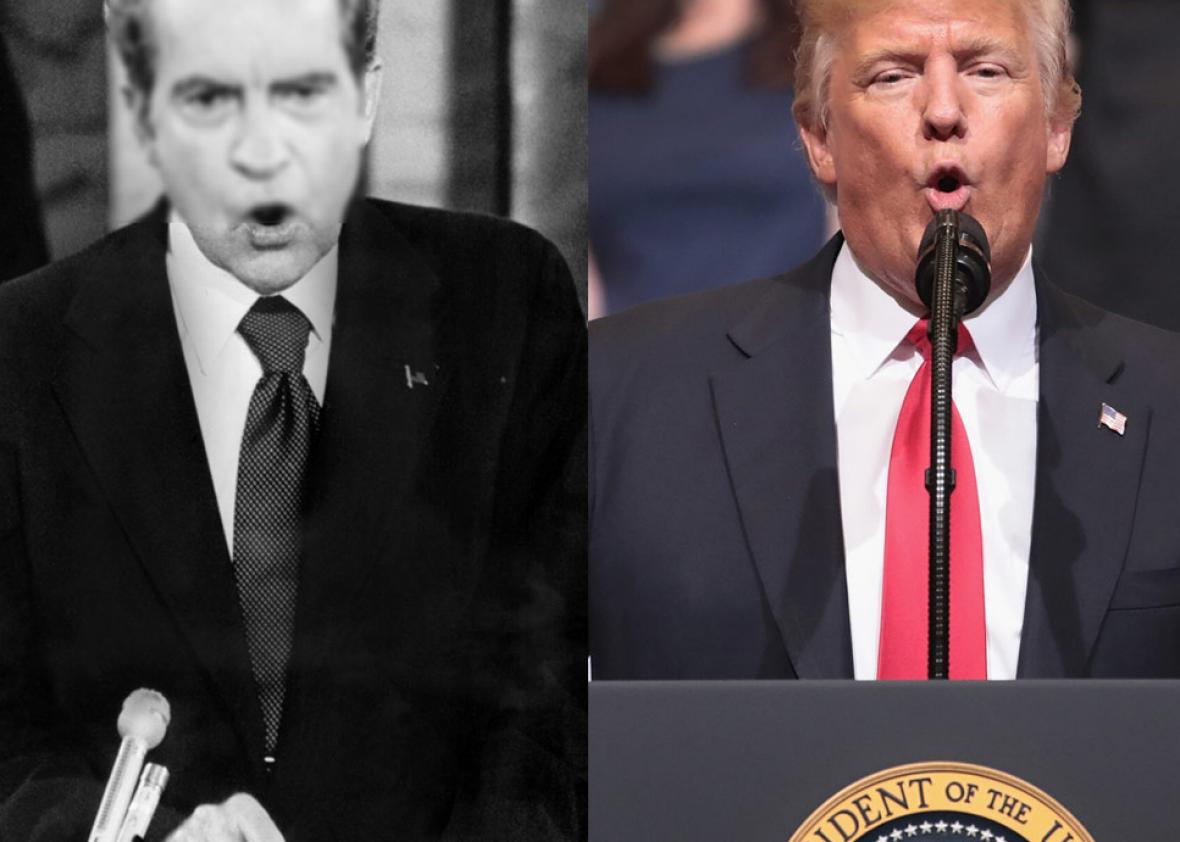

In the latest issue of New York magazine, Frank Rich has a terrific cover story, “Just Wait: Watergate didn’t become Watergate overnight, either.” “[A]mong those of us who want Donald Trump gone from Washington yesterday, there’s a fair amount of fear that he, too, could hang on until the end of a four-year term that stank of corruption from the start,” writes Rich. But the Watergate example, he argues, shows that the implosion of a presidency isn’t necessarily obvious as it’s happening.

As Rich points out, there are many fascinating similarities between Donald Trump’s emerging Russia scandal and Watergate. Both involved break-ins to the Democratic National Committee and high-level firings aimed at impeding the resulting investigation. Nixon, like Trump, was a resentful and paranoid man obsessed with curbing leaks by the government officials whom he believed were conspiring against his administration. (Nixon referred to his internal enemies as the “counter-government”; Trump calls them the “deep state.”) At the moment, however, the most salient parallel between the Trump–Russia scandal and Watergate might lie in the frustrating, stop-start way it is unfolding and the collective uncertainty about who it will ensnare. Rich quotes Elizabeth Drew, then the New Yorker’s Washington columnist: “In retrospect, the denouement appeared inevitable—but it certainly didn’t feel like that at the time.”

It’s worth remembering this in the twitchy interregnum between revelations when people on both the right and the left are arguing that the Trump–Russia scandal is an elite preoccupation distant from the concerns of the electorate. In the New York Times, David Brooks cautions against getting “carried away” by the Trump–Russia investigation: “Political elites get swept up in the scandals. Most voters don’t really care.” According to Mike Lillis at the Hill, some Democratic members of Congress want their leaders to talk less about Trump and Russia, saying that the “narrative is simply a non-issue with district voters, who are much more worried about bread-and-butter economic concerns like jobs, wages and the cost of education and healthcare.”

As a strategic argument, this might make sense: Most people are always going to be more worried about their immediate economic prospects than even the most rococo of Washington misdeeds. But public interest in an unfolding scandal doesn’t tell us much about the ultimate danger it poses to the administration. In a March 13, 1973 conversation with Dean, Nixon dismissed the idea that Watergate was a potential crisis. “It’ll be mainly a crisis among the upper intellectual types, the assholes. … Average people won’t think it is much of a crisis unless it affects them,” he said. He was right—until he wasn’t.

That March, Nixon’s approval rating was close to 60 percent. It wouldn’t sink as low as Trump’s current 36 percent until months after the Senate hearings began. It never dropped lower than 24 percent, which may be close to Trump’s floor; a poll last month found 22 percent of the electorate strongly approve of the president. Rich argues that, contrary to popular mythology, Republicans in Nixon’s time were no braver or less craven than our own. They didn’t jump ship until the president had become politically toxic. By the summer of 1974, Rich writes, with “the midterms growing ever nearer, garden-variety GOP officeholders, most of them as cowardly as today’s, started to flee.”* In August, the transcript of the “smoking gun” tape conclusively revealed that Nixon had ordered the Watergate cover-up, and the dam on the president’s remaining political support finally broke.

In a series of tweets on Monday morning, Trump wrote, “With 4 months looking at Russia under a magnifying glass, they have zero ‘tapes’ of T people colluding.” It’s notable that Trump is moving the scandal goalposts away from evidence of collusion to the existence of “tapes.” He’s doing this at a time when right-wing pundits are arguing that even if evidence of the Trump campaign’s collusion with Russia does emerge, such collusion is not criminal. Perhaps a new bombshell is going to drop soon and the right is trying to pre-emptively defuse it. But whatever happens, four months is nothing in an investigation like this. It doesn’t matter if Americans think this scandal is the most important threat facing the country. It’s still the most important threat facing the president.

*Correction, June 27, 2017: This story originally misstated this as the summer of 2014. It was the summer of 1974. (Return.)