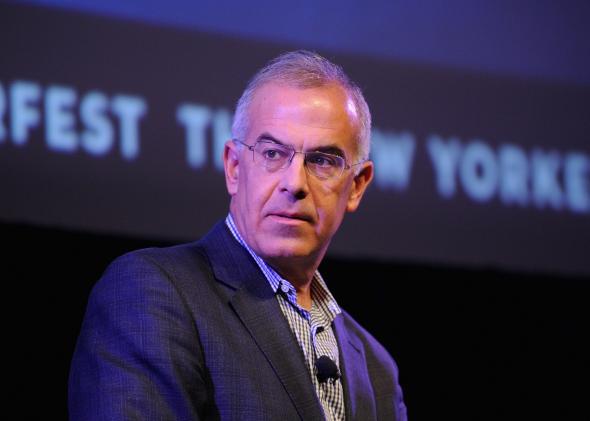

David Brooks has developed a reputation for wisdom as a writer for the New York Times. It’s true that he occasionally stumbles upon insights, as he does, for example, in his writing on emerging neuroscience. But he is consistently wrong-headed when he takes on issues relating to poverty. His instinct is always to discuss the problem in terms of virtue and morality; material factors and structural conditions are afterthoughts. Thus his columns on the poor end up being something closer to 800-word rants masquerading as high-minded journalism. It’s never enough for him to batter you with erudition; he insists on moralizing as well.

On Friday, Brooks published another fatuous piece about poverty. This time, naturally, the subject was Baltimore. Brooks tried to undercut the popular trope that funding poor communities like Baltimore will improve conditions. He writes:

The $15 trillion spent by the government over the past half-century has improved living standards and eased burdens for millions of poor people. But all that money and all those experiments have not integrated people who live in areas of concentrated poverty into the mainstream economy.

This passage is instructive for a couple of reasons. First, it illustrates Brooks’ tendency to say something true without offering anything resembling context. For instance, he notes that poor people haven’t been integrated into the mainstream economy but fails to ask why that is. We’ve tossed all this money at the problem, he seems to suggest, yet things aren’t better. How could that be? Perhaps it has something to do with history, with the residual effects of institutionalized racism and the array of structural problems that have plagued Baltimore and communities like it for decades. Dumping federal dollars into a city doesn’t erase these things.

What Brooks wants to do is advance a pleasant-sounding bootstraps argument: Those poor people just need to lift themselves out of poverty through moral education and self-reliance. He continues: “But the real barriers to mobility are matters of social psychology, the quality of relationships in a home and a neighborhood that either encourage or discourage responsibility, future-oriented thinking, and practical ambition.” Here Brooks identifies the real problem with poor people: They lack high-quality relationships and strong familial ties. That’s not entirely false, but it’s also embarrassingly incomplete.

Brooks shows no interest in examining antecedent causes. He doesn’t consider, for example, how the patently racist drug war or the history of speculative real estate practices in places like Baltimore have destroyed families by breaking up homes and obliterating financial stability. Brooks even references a recent David Simon interview to buttress his point. According to Simon, Brooks writes, “even in Baltimore, there once were informal rules of behavior governing how cops interacted with citizens … but then the code dissolved. The informal guardrails of life were gone.”

He conveniently forgets to mention the drug war, however, which Simon has spoken eloquently about and dedicated his acclaimed television series to exploring—and which Brooks blithely ignores. In addition to incentivizing bad police work, the drug war has savaged entire communities by locking up nonviolent offenders and creating local economies that are devoid of meaningful work. What’s more, when those nonviolent offenders (like Freddie Gray) are released from jail, they’re essentially unemployable. It’s impossible to overstate how deep and broad the consequences of these policies truly are. The $15 trillion Brooks cites in his column did nothing to change this dynamic.

Predictably, Brooks returns to his long-running narrative about the moral failures of poor people. “Individuals,” he observes, “are left without the norms that middle-class people take for granted. It is phenomenally hard for young people in such circumstances to guide themselves.” As usual, Brooks is half-right. Yes, it’s quite hard for people in these circumstances to “guide themselves.” But the question he fails to ask is why are “middle-class” norms lacking in these communities?

It doesn’t occur to Brooks that middle-class virtues are infinitely more difficult to practice (and cultivate) in abject poverty. He assumes that prosperity is a product of such virtues. In reality, the reverse is closer to the truth. For Brooks, middle-class people have done well because of their values. But it’s more complicated than that. The success of white America (which constitutes a majority of the middle class) stretches back hundreds of years and is predicated, in part, on the exploitation of black America. That’s an uncomfortable fact and one to which Brooks is blind. It’s relevant because the damage done by these structural inequities persists, and they are part of the poverty picture that Brooks ignores.

For Brooks, the problem with poor people is that they’re immoral. It’s not because they’re structurally disadvantaged, or because their local economies have collapsed, or because jobs have been shipped overseas, or because they attended chaotic schools, or because their parents worked multiple jobs for unlivable wages, or because the material demands of existence occupy the bulk of their time. Nope, it’s because of poor “social psychology.”

That’s the kind of explanation that could only be offered by someone oblivious to his own advantages. And Brooks has been peddling it for years.