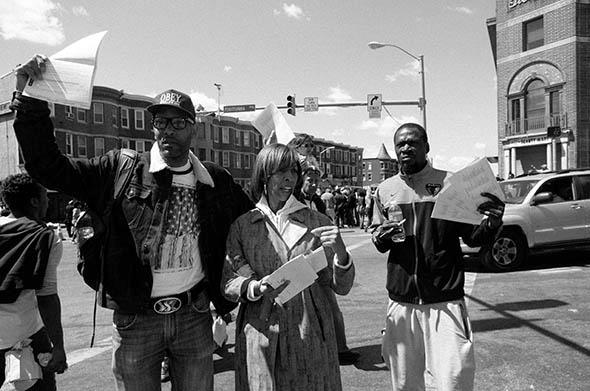

BALTIMORE—“We want people to register to vote, because that’s where the change is made,” said State Sen. Catherine Pugh, standing near the smoldering remains of the CVS on North Avenue, and handing voter registration forms to anyone who caught her eye. The street was thick with people—children on a day off from school, adults from the neighborhood, a few street musicians, an incense-waving activist, at least two men with bullhorns, and a gaggle of reporters—and it was a good day for any politician to show her face and shake a few hands. After handing a form to a young man and giving him a pen to fill it out, she turned back to finish her pitch for why this—more than ever—was the time for traditional political action. “I am a senator, I was a city council member. I know that by being there, it does make a difference, and if you don’t vote, it doesn’t happen.”

Pugh is a politician, and politicians—if they do anything—support the system they serve. But you can forgive the residents of West Baltimore—and East Baltimore, both united by huge blocks of long vacant homes and long boarded businesses—if they’re cynical about civic engagement. Since the civil rights movement, but especially since the 1968 riots—sparked by Martin Luther King’s assassination after 15 years of nonviolent protest—Baltimore has been a largely black city. This is mostly a function of population decline, stemming from the riots. From 1970 to 2000, the city’s population fell by nearly one-third, from 906,000 to 651,000. At the same time, the number of black residents rose. In 1950, just 24 percent of Baltimoreans were black. By 1980, it was 54 percent, and by 2000, it was 65 percent.

Now, Baltimore is a city of 620,000, and the large majority—63.7 percent—are black. And unlike Ferguson, where demographic strength lagged political representation, Baltimore’s black residents have turned their presence into black mayors, black city councils, and black representatives to Annapolis. Far from a rarity, black leadership in Baltimore is a given that even extends to the police. Throughout the 1980s, the city worked to bring black Americans on to the force and promote them up through the ranks. As writer Stacia Brown notes for the New Republic, “The city believed the presence of black people in politics and law enforcement could foster greater trust and more open communication between black citizens and their government.”

All of this was a vital and admirable contribution to the city’s civic life. And yet, the basic position of Baltimore’s low-income blacks didn’t change.

In the Sandtown-Winchester neighborhood where Freddie Gray lived before he died in police custody on April 12, one-half the residents are unemployed and one-third of the homes are vacant. Sixty percent of residents have less than a high school diploma, and the violent crime rate is among the highest in Baltimore. You can paint a similar picture for the neighborhoods and housing projects on the east side of the city as well. If you are poor and black in Charm City, your life—or at least your opportunity to have a better life—looks bleak.

But then, this is by design. In the early 20th century—as in many American cities—Baltimore civic leaders endorsed broad plans to “protect white neighborhoods” from black newcomers. The city was flush with waves of immigration—from abroad as well as the South—and more affluent blacks were leaving the older, poorer neighborhoods to move to predominantly white areas removed from the poverty and joblessness of the crowded slums. In short order, politicians and progressive reformers—motivated by benevolence, politics, and an en vogue scientific racism—endorsed segregation plans and racial covenants meant to cordon blacks—as well as Italian and Eastern European immigrants—on to small parts of land in the inner city.

Photo by Jamelle Bouie

By the 1930s, black Americans had grown to 20 percent of Baltimore’s population but were confined to 2 percent of the city’s landmass. And there was desperate need for new housing, as both formal and informal segregation kept blacks from expanding neighborhoods or moving into white areas (the same was increasingly less true of European immigrants, who—with upward mobility—could integrate into mainstream society). In the 1940s, local, state, and federal leaders pushed public housing to relieve the crisis. But it was segregated. Blacks would receive new housing in their neighborhoods, and working-class whites—in turn—would receive new homes in their own. Five of six public housing projects—McCulloch, Poe, Gilmor, Somerset, and Douglass—would be placed in the most dense black neighborhoods of East and West Baltimore. And while the war boom would deliver partial prosperity, many of these areas still lacked a stable employment base, even as they continued to grow with rapid influxes of new black residents.

In 1950—following complaints from white residents over plans to expand public housing—the mayor and the City Council agreed to limit future building to existing “slum sites” where the majority of blacks lived. As they had done for the past four decades, white leaders prepared to limit black migration in the city as much as possible. But there was still a housing problem; blacks were still moving to Baltimore, and there weren’t enough units for the new residents. Both dynamics, working together, led to a decade-long project of “urban renewal,” as the city used federal funds for “slum removal” to make way for new, high rise public projects. Renewal displaced 25,000 Baltimoreans—almost all of them black—and the new high-rises were built with segregation in mind. By the time construction was finished, the new projects had bolstered and entrenched the segregation of the past. The black areas of 1964—and of the 1968 riots—are almost identical to the black areas of 50 years prior.

There is much, much more to this story. The key part, however, is the remarkable stability of Baltimore’s segregation over time. By and large, the “Negro slums” of the 1910s are the depressed projects and vacant blocks of the 2010s. And the same pressures of crime and social dislocation continue to press on the modern-day residents of the inner city. If the goal of early segregationist policies was to concentrate black Baltimoreans in a single location, separated from opportunity, then it worked. More importantly, it’s never been unraveled; there’s never been a full effort to undo and compensate for the policies of the past. Indeed, the two decades of drugs and crime that marred Baltimore in the 1980s and 1990s helped entrench the harm and worsen the scars of the city’s history.

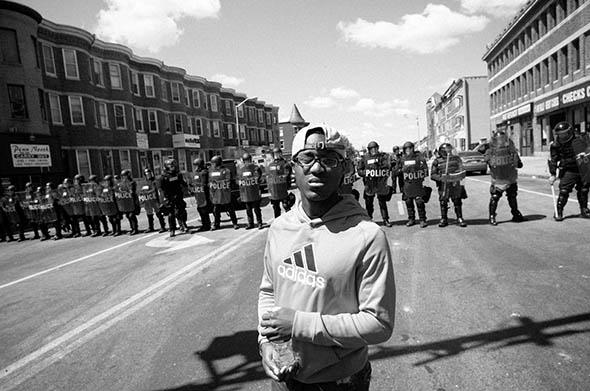

Photo by Jamelle Bouie

Baltimore is stuck, captured by the injustices of the past as well as the countless individual choices of the present. The city’s ills—its poverty, its fatherlessness, its police violence—are rooted in these same patterns of segregation and discrimination. This isn’t an excuse—Baltimore has had a generation of politicians, white and black, who can renovate tourist areas and implement new police techniques, but who can’t provide relief and opportunity to its most impoverished residents—but it is important context. Even at their absolute best, the city’s leaders have to contend with the cumulative impact of past disadvantage. White flight means a smaller tax base and fewer resources for improvement; industrial collapse means fewer jobs; crack and violence means a generation of “missing” black men, in jail or in the ground; a culture of police violence means constant tension with the policed.

The simple fact is that major progress in Baltimore—and other, similar cities—requires major investment and major reform from state and federal government. It requires patience, investment, and a national commitment to ending scourges of generational poverty—not just ameliorating them. But that’s incredibly difficult, and it’s not clear there’s any political will to pursue potential solutions. Or, as President Obama said in his remarks on the Baltimore riots, “If our society really wanted to solve the problem, we could. It’s just it would require everybody saying this is important, this is significant.”

On Tuesday morning, small groups of people came from across Baltimore to help clean up the wreckage from the previous night, working through the day to sweep glass, remove debris, and help neighbors harmed by looting. “At first, I was pissed off,” explained Crystal, who witnessed the riots from her home in West Baltimore. “But now I’m proud. I’ve never seen such unity,” she said, pointing to groups of people sweeping trash from the sidewalks and hauling bags of litter to nearby dumpsters.

Photo by Jamelle Bouie

She wasn’t exaggerating. Even as armored cars and police blocked streets and patrolled the area, there was a real feeling of community at the intersection of North and Pennsylvania Avenues. Some residents, like one young woman who took the day off, gave water and food to volunteers, while others spread word of churches and other open spaces where children and teenagers—school was canceled, a casualty of the riots—could study, talk to adults about the turmoil, and grab a meal. Opinions varied on the riots—“I don’t support this, let’s get that straight right now… cops were wrong, but this was wrong,” said Raquel, who works with elementary school students—but there was a general sense that, as another woman explained, “Baltimore takes care of its own.” It’s why, at a community meaning that evening, residents (joined briefly by Martin O’Malley, the former Maryland governor and Baltimore mayor) made plans to deliver food to school children, run errands for the elderly, and try as much as possible to keep a presence on the streets to prevent any bad behavior.

This spirit wouldn’t last. At dusk, the crowd at the intersection had begun to get restless. By nightfall, face-to face-with armed riot police, people were eager for action. It didn’t help that Baltimore was under a curfew, announced on Monday. By 10 p.m., the curfew time, demonstrators and community leaders—including Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake and House Rep. Elijah Cummings—had gotten hundreds of people out of the street. But, in addition to media, there were dozens of people left, throwing rocks and bottles at the line of officers. After a tense, half-hour standoff, police would act, using tear gas and rubber bullets to break the crowd and clear the streets.

It was much better than it could have been. It was also a disappointment. For the second time in two nights, the intersection was marked with chaos and debris. And while volunteers can continue to clean the streets and repair the damage, the anger remains, fueled by recurring—and almost unending—deprivation.