Say what you will about Justice Samuel Alito, but the man always thinks ahead. On Monday, Alito dissented in Cooper v. Harris, the landmark 5–3 ruling that united Justice Clarence Thomas and the Supreme Court’s liberals to strike down North Carolina’s racial gerrymander. Frustrated by the progressive result, Alito penned a 34-page broadside lambasting his colleagues for accusing the state of race-based redistricting. North Carolina, Alito insisted, had gerrymandered along partisan lines, not racial ones, in an effort to disadvantage Democrats, not blacks. And partisan gerrymandering, Alito reminded us, does not violate the Constitution.

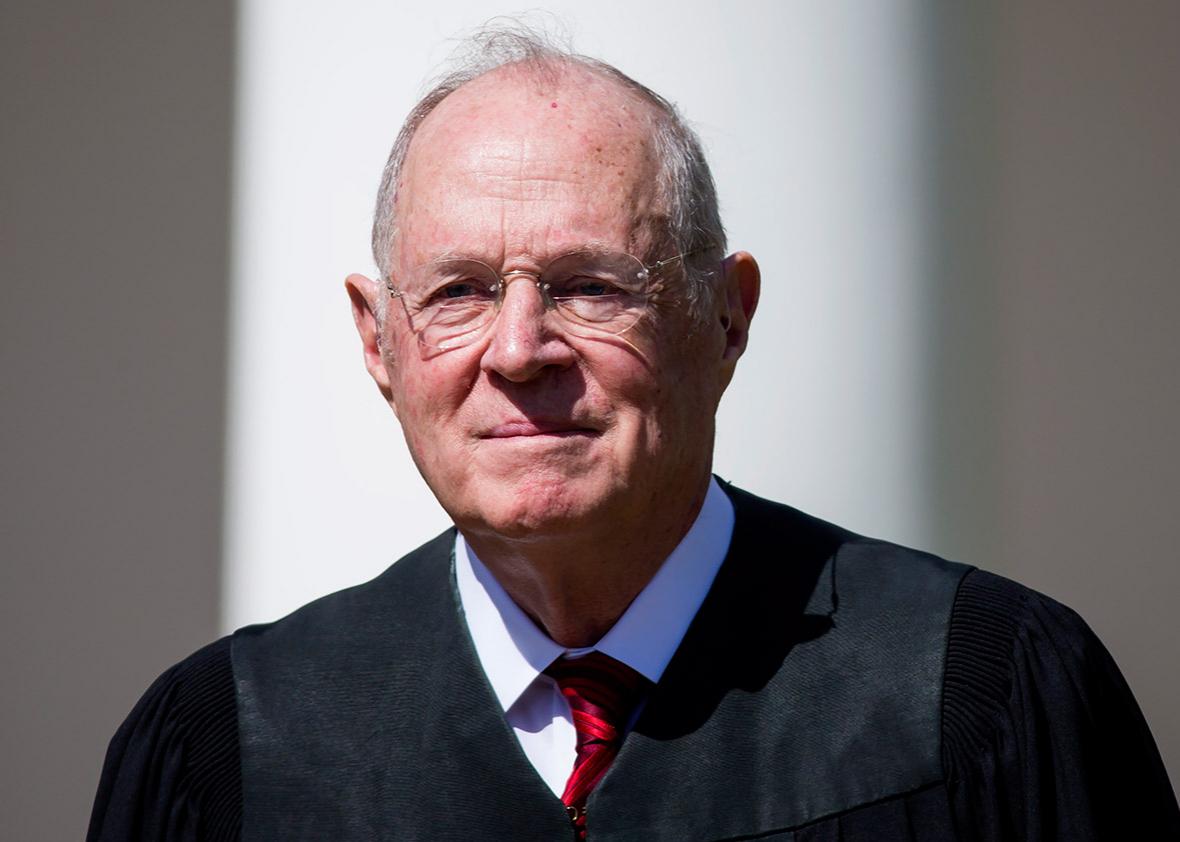

In fact, the constitutionality of partisan gerrymandering is a matter of extensive debate—and the Supreme Court will almost certainly decide its fate next term in a blockbuster case called Gill v. Whitford. Alito, it seems, is already gearing up for Whitford. His Harris dissent is peppered with warnings about the hazards of judicial intervention into political redistricting disputes. Alarmingly for voting rights advocates, Justice Anthony Kennedy joined the opinion in full, lodging no protest against the passages framing partisan gerrymandering as constitutionally permissible politics as usual. Given that Thomas has no issue with partisan (as opposed to racial) gerrymandering, the plaintiffs will likely need Kennedy’s support to pull off a victory in Whitford. But his vote on Monday suggests the justice might not be ready to take down partisan gerrymandering.

It was Kennedy himself who penned the opinion that serves as a kind of treasure map for gerrymandering opponents. Vieth v. Jubelirer, handed down in 2004, appeared to present the court’s conservatives with an opportunity to rule that partisan redistricting does not infringe upon any constitutional rights. Instead, the court split badly on the case. While five justices agreed that partisan gerrymanders can violate the Constitution, one of those five—Kennedy—wasn’t ready to invalidate them. In his concurrence, he asserted that nobody had yet presented a consistent method of identifying and fixing unconstitutional political redistricting. Until that happened, he wrote, the court should not wade into these debates.

Kennedy’s Vieth concurrence established the specific constitutional infirmity in gerrymanders. They can, he explained, “burden representational rights” by “penalizing citizens” because of their “association with a political party” or their “expression of political views”—a form of viewpoint-based discrimination prohibited by the First Amendment. Since 2004, this problem has become much more pronounced. When the GOP swept state legislatures in 2010, Republican operatives instituted project REDMAP, or the Redistricting Majority Project, which used sophisticated analyses to pack Democrats into a few districts then distribute the rest throughout safe Republican districts.

Project REDMAP effectively deprived millions of voters of what Kennedy called “representational rights”: the ability, fundamental in any democracy, to choose one’s representatives. Previously purple states like Wisconsin were so gerrymandered that many Democrats had no real hope of electing their preferred candidates—their votes were too diluted to matter. But until someone developed a reliable, Kennedy-approved method of measuring the constitutionality of redistricting, these voters had little recourse in the courts.

Now two scholars, Nicholas O. Stephanopoulos and Eric M. McGhee, think they’ve found a standard that would satisfy Kennedy. Their formula, which they call the efficiency gap, measures two types of “wasted votes”: “lost votes” cast in favor of losing candidates and the “surplus vote” cast in favor of the winning candidate beyond the number she needs to win. The efficiency gap is the difference between each party’s wasted votes in an election divided by the total number of votes cast.

When both Democrats and Republicans waste the exact same number of votes, the efficiency gap is zero. That means the race was genuinely competitive, and voters on both sides had a real shot at electing their candidate. As the majority gerrymanders its opponents, though, it will “waste” fewer votes, leading the efficiency gap to climb. Stephanopoulos and McGhee conducted a historical analysis of elections since 1972 suggesting that an efficiency gap of 7 is sufficient to entrench a party’s legislative monopoly. They believe the courts should use this metric to gauge partisan gerrymanders, rejecting those that create a massive efficiency gap as an unconstitutional burden on representational rights.

Alito sees things very differently. In his Harris dissent, the justice suggests that, when a court blocks a partisan gerrymander, “it illegitimately invades a traditional domain of state authority, usurping the role of a state’s elected representatives.” And what if those representatives are discriminating against voters on the basis of political affiliation? To Alito, that’s a political problem, not a constitutional one. If the courts allow minority parties to sue against partisan redistricting, Alito wrote, “they will invite the losers in the redistricting process to seek to obtain in court what they could not achieve in the political arena.” He continued:

If the majority party draws districts to favor itself, the minority party can deny the majority its political victory by prevailing on a racial gerrymandering claim. Even if the minority party loses in court, it can exact a heavy price by using the judicial process to engage in political trench warfare for years on end.

It is startling to hear Alito use the term political victory to describe a state’s successful effort to punish voters of a certain party by diluting the power of their votes. In any other context, this discrimination would clearly run afoul of the First Amendment’s guarantees of free association and expression. But when it comes to redistricting, Alito disregards basic constitutional principles, giving states free rein to target and disadvantage their political opponents.

Kennedy’s willingness to join Alito’s admonition means, at the very least, that a progressive outcome in Whitford is far from assured. On Tuesday, I asked Paul Smith, who is working with the Campaign Legal Center to bring Whitford before the Supreme Court, whether Kennedy’s vote in Harris unsettled him. Smith pointed out that the question in Harris was whether legislatures could use race as a proxy for party in redistricting, not whether party affiliation itself is an invalid consideration.

“I am skeptical that one can glean much from this case about where the court, and Justice Kennedy in particular, will land in Whitford,” Smith told me. “At most, the dissent stands for the proposition that as long as it’s legal for a majority of legislators to seek to inject partisan bias into a map, they should not be deprived of that chance based on a debatable claim of racial predominance. One might argue that the case demonstrates the difficulty of separating race and party in some states and may encourage the court to reach a ruling that both goals raise constitutional problems.”

Smith is obviously correct that Harris doesn’t dictate the outcome of Whitford. But Kennedy’s vote could still presage trouble for the case. In his Vieth concurrence, Kennedy seemed revolted by the constitutional harms inflicted by gerrymandering. Now he has joined a dissent contending that the real harm would arise from courts trying to stop overtly partisan redistricting. Monday’s decision was a triumph for democracy. But the bigger fight looms just ahead—and Kennedy’s vote appears to be as shaky as ever.