On Monday, the Supreme Court issued a landmark decision holding that two congressional districts in North Carolina were racially gerrymandered in violation of the Constitution. The broad ruling will likely have ripple effects on litigation across the country, helping plaintiffs establish that state legislatures unlawfully injected race into redistricting. And, in a welcome change, the decision did not split along familiar ideological lines: Justice Clarence Thomas joined the four liberal justices to create a majority, following his race-blind principles of equal protection to an unusually progressive result.

Cooper v. Harris, Monday’s case, involves North Carolina’s two most infamous congressional districts, District 1 and District 12. In the 1990s, the Democratic-controlled state legislature gerrymandered both districts into bizarre shapes that appeared to be drawn along racial lines. A group of Republican voters sued, arguing that the state had used race to shape the districts in violation of the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause. North Carolina acknowledged that it had used race in redistricting, but argued that it did so for a constitutionally permissible reason: It wanted to comply with the Voting Rights Act, which bars states from diluting minority votes and, at the time, required the creation of majority-minority districts in historically racist states. To ensure compliance with the VRA, North Carolina asserted, it had drawn both districts to be majority black.

In 1996’s Shaw v. Hunt, the Supreme Court ruled by a 5–4 vote that these districts violated equal protection. In this case, the conservatives formed the majority, while the liberal justices would have affirmed the constitutionality of the racially gerrymandered districts. At the time, progressives viewed Shaw and its predecessors as an assault on the VRA—a Republican effort to prevent states from helping black voters choose their own representatives. The liberal justices, on the other hand, saw many racial gerrymanders as a kind of affirmative-action program. They insisted that North Carolina’s districts were merely “designed to accommodate the political concerns of a historically disadvantaged minority.”

There was some truth to this idea, but also a great deal of naïveté. The majority-black districts that progressives defended were frequently drawn with the help of Republicans, who appreciated the clustering of Democratic voters around a few safe seats. By packing black Democrats into a handful of districts, Republicans made their own seats safer. Had the Supreme Court’s conservatives held fast on Shaw, these majority-black districts might have been invalidated. But in 2001’s Easley v. Cromartie, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor unexpectedly flipped, siding with the liberals to ease restrictions on racial gerrymandering. Easley cemented the notion that states may gerrymander along partisan lines, even where race and political affiliation are intertwined. Since then, plaintiffs have struggled to prove that gerrymanders used race as a “predominant factor” (illegal) rather than party registration (legal).

Fast forward to today, and it is overwhelmingly obvious that the logic of Cromartie has backfired on progressives. Republican-dominated state legislatures are now notorious for brazen racial gerrymanders, kicking black voters out of GOP districts and herding them into safe Democratic ones instead. The result is an extreme partisan imbalance in dozens of state legislatures: In Southern states especially, Republicans have granted themselves huge majorities and left Democrats with a few safe, often majority-minority seats. Black voters routinely sue and occasionally win, but time and again they face the same problem: The legislature claims it was using race as a mere proxy for partisanship, and the courts throw out the plaintiffs’ lawsuit, citing Cromartie.

That era ended on Monday. In a deft opinion by Justice Elena Kagan, the court essentially scraps Cromartie’s race vs. party distinction, replacing it with a more lenient rule. Kagan accomplishes this switcheroo in a footnote that will serve as the basis of innumerable future lawsuits, stating that courts may find proof of an unlawful racial gerrymander “when legislators have placed a significant number of voters within or without a district predominantly because of their race, regardless of their ultimate objective in taking that step.” Kagan continues:

So, for example, if legislators use race as their predominant districting criterion with the end goal of advancing their partisan interests—perhaps thinking that a proposed district is more “sellable” as a race-based VRA compliance measure than as a political gerrymander and will accomplish much the same thing—their action still triggers strict scrutiny. In other words, the sorting of voters on the grounds of their race remains suspect even if race is meant to function as a proxy for other (including political) characteristics.

Kagan then reviewed the evidence collected by the trial court, which had concluded that North Carolina’s gerrymander was primarily driven by race and failed to meet strict scrutiny. This finding, Kagan writes, was not “clearly erroneous”—the standard of review in racial-gerrymander cases. Thus, the trial court’s ruling striking down both districts must stand.

Amusingly, Kagan frames her opinion as little more than a pedestrian application of precedent. As election law expert and Slate contributor Rick Hasen writes, however, it is much more than that. The decision, Hasen explains, “means that race and party are not really discrete categories” in states where race is closely tethered to party, especially in the South. That means a legislature can no longer use race as a proxy for party in redistricting, then insist that it was really discriminating against Democrats, not blacks. “This will lead to many more successful racial gerrymandering cases in the American South and elsewhere,” Hasen speculates.

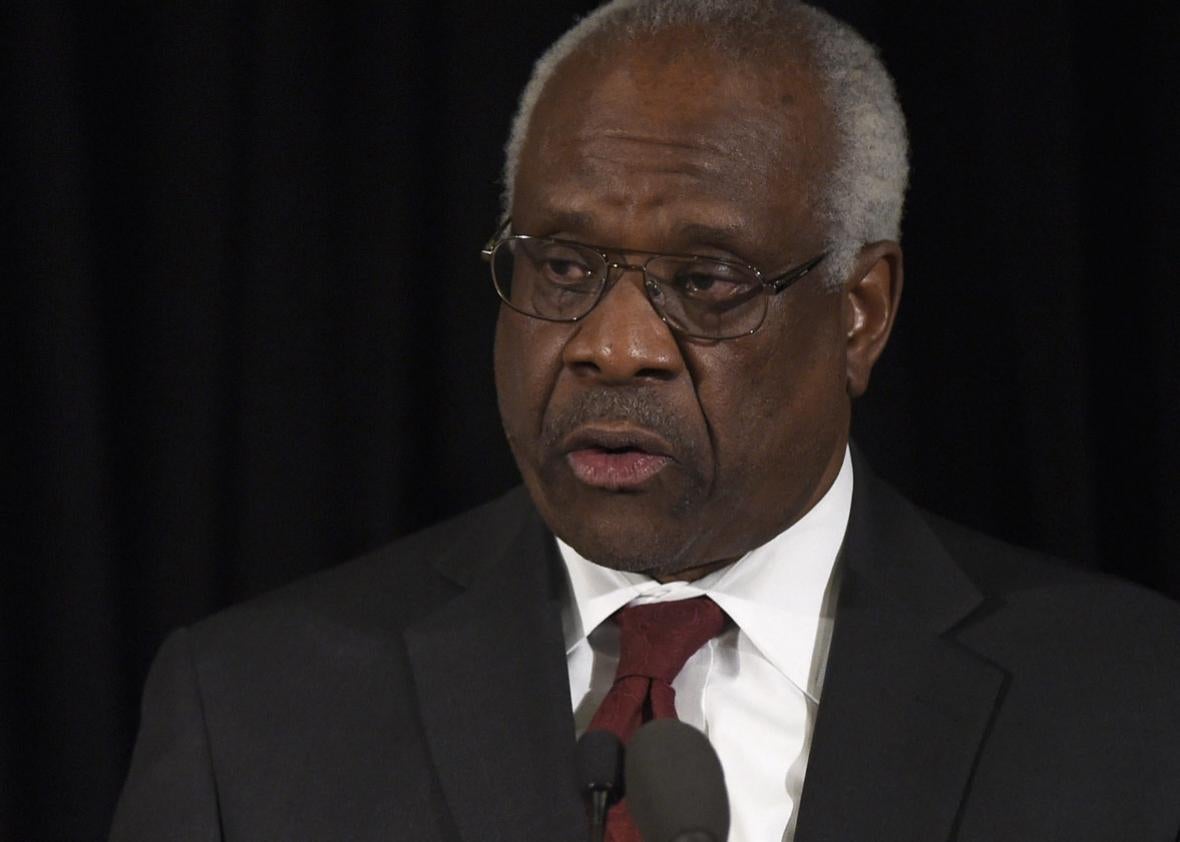

Given the advantage that Harris could give to Democrats, it may seem puzzling that Thomas, of all justices, cast the deciding vote to give the liberals a majority. But really, his vote should not have been a surprise at all. Thomas is arguably the most consistent justice on racial gerrymandering: He opposes it no matter its ostensible purpose. In the 1990s, Thomas disapproved of race-conscious redistricting designed to empower black Democrats; today, he objects to race-conscious redistricting designed to empower white Republicans. While liberals and conservatives switched sides, Thomas stuck to his guns. And on Monday, his consistency handed Democrats—and the principle of equality—a remarkable victory.

Unfortunately, Harris will not singlehandedly fix the problem of gerrymandering in America. So long as partisan gerrymandering remains legal, legislators will continue to draw districts that disfavor the opposing party, entrenching their own power for years. Next term, the Supreme Court will almost certainly hear Gill v. Whitford, a challenge to partisan redistricting alleging that the practice discriminates on the basis of political association, violating voters’ free-speech and equal-protection rights. The outcome of that case could permanently alter American politics by proscribing either party from using political gerrymanders to seize and maintain a legislative monopoly. Harris was a satisfying appetizer. But Whitford will be the main course.