On Tuesday the Supreme Court voted 5–4 to affirm a lower-court decision that allowed Texas’ sweeping new abortion restrictions to take effect. The court’s decision is not the final word on the Texas law, just a prediction about the future prospects of the challenge, but it hints at the fact that the court might ultimately uphold the law. The decision also raises new questions about whether the court is more conservative on abortion than we assume.

Conventional wisdom holds that the court is evenly split on abortion (and virtually every other social issue) and that Justice Anthony Kennedy is the “swing justice.” We can reasonably predict that Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Antonin Scalia, Clarence Thomas, and Samuel Alito will vote to uphold any restriction on abortion and would probably all vote to overturn Roe v. Wade as well. On the other hand, we’re confident Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan will vote to overturn almost all restrictions and would certainly vote to preserve Roe.

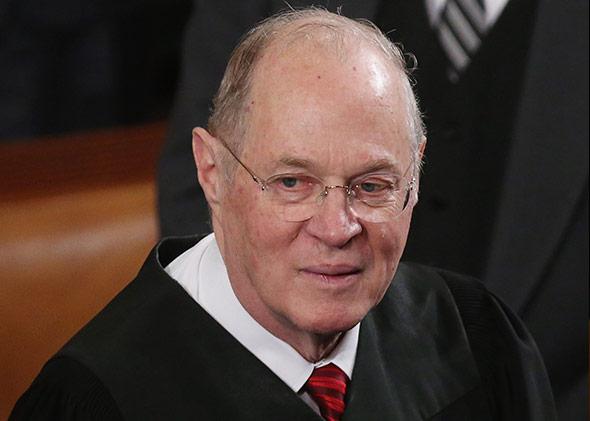

So that leaves Kennedy in the powerful middle. He alone, the story goes, determines the fate of reproductive rights in this country. Unlike the others, his mind isn’t made up on the issue, and all arguments have to be directed to him, just as they were to past swing justices Lewis Powell and Sandra Day O’Connor.

The argument that Kennedy is firmly in the center on abortion and can swing the issue one way or the other rests on two different pillars. First, Kennedy surprised the world in 1992 when he switched his vote and joined four other justices in upholding Roe. In Planned Parenthood v. Casey, he justified affirming Roe with flowery language about the importance of abortion to women’s dignity, autonomy, and self-definition.

Second—again in Casey—Kennedy was part of the majority that struck down Pennsylvania’s requirement that married women notify their husbands before they obtain an abortion. The opinion cited domestic violence statistics to justify the conclusion. It reasoned that many women might fear talking about a termination with their husband, so for those women the requirement is unduly burdensome.

Despite these two nods in the direction of abortion rights, the conventional wisdom about Kennedy is wrong. Instead of being a swing vote on abortion, Kennedy is actually just short of being as absolutist as universally known anti-abortion Justices Scalia and Thomas. Looking closely at what Kennedy has actually done during his time on the court with respect to abortion proves this.

From joining the court in 1988 to this week’s decision in the Texas case, Kennedy has been involved in 12 cases addressing abortion restrictions. In those 12 cases, he has voted on whether 21 different abortion restrictions could take effect. We already know that he voted to strike down Pennsylvania’s husband notification requirement. Besides that, how many of the other 20 restrictions has Kennedy voted to block from taking effect? Exactly zero.

You read that correctly. The so-called swing justice, Anthony Kennedy, has voted to strike down only one of the 21 abortion restrictions that have come before the Supreme Court since he became a justice. Put another way, in his time on the court, Kennedy has voted to allow each of the following provisions to go into effect (in chronological order): an antiabortion preamble to abortion legislation, a restriction on public employees/facilities performing abortion, an exacting requirement for determining viability, a judicial bypass procedure, a requirement that the physician notify a minor’s parent, a two-parent notification requirement, a two-parent judicial bypass exception, a narrow definition of medical emergency, a strict informed-consent requirement, a parental consent requirement, a 24-hour waiting period, strict recordkeeping and reporting requirements, a prohibition on public funding of abortion, an extensive regulation of abortions after 20 weeks, a different judicial bypass procedure, a physician-only requirement, a state “partial-birth” abortion prohibition, a parental notification law without a health exception, the federal “partial-birth” abortion prohibition, and, in Texas earlier this week, a requirement that doctors have admitting privileges at a local hospital.

The fact that Kennedy is not nearly as moderate as we like to imagine on abortion becomes even more apparent when you branch out from abortion restrictions to cases peripherally addressing abortion. Most of these cases have dealt with restrictions on protesting near abortion clinics, but they have also addressed other issues, such as importing the abortion pill (before it was approved in the United States) and counseling restrictions for doctors receiving federal funds.

Since Kennedy joined the court, there have been 10 such peripheral abortion cases. Looking closely at them, we can see almost the same track record as with the more obvious abortion restrictions. In eight of these cases, Kennedy voted against the interests of abortion rights. What about the other two cases then? Maybe those prove he swings on abortion. Both of those cases were so uncontroversial in the context of abortion that Kennedy’s vote was joined by other justices who are universally perceived as against abortion. In both cases, Chief Justice William Rehnquist and Justice Byron White (the original dissenters in Roe) joined Kennedy, as did Scalia and Thomas (Thomas only joined for one; he wasn’t on the court for the other). In other words, if these two votes in peripheral abortion cases make Kennedy a “swing justice” on abortion, then they would also make the court’s staunchest antiabortion justices swing justices.

Further evidence that Kennedy is not a swing vote in the opinions he has authored about abortion: The language he wrote in Casey about dignity, autonomy, and self-definition was technically jointly authored by three Justices—Kennedy, O’Connor, and David Souter. Since then, however, when Kennedy has authored opinions himself about abortion, he has been blistering.

In 2000 he dissented from the court’s decision that a Nebraska restriction on second-trimester abortions was unconstitutional. Kennedy’s dissent uses language straight out of the antiabortion movement’s talking points. He calls the doctor an “abortionist.” He calls the fetus “unborn” life. He calls the abortion procedure at issue one that “many decent and civilized people find so abhorrent as to be among the most serious of crimes against human life.” He was arguably even worse in 2007 when he wrote the opinion for the court upholding a federal version of the Nebraska law. In that case, he likened the procedure to “infanticide” and paternalistically talked about the importance of preventing women from having “regret” about their decisions. In dissent, Ginsburg was so angered by Kennedy’s language that she accused him of having “hostility” toward the right to abortion and invoking an “antiabortion shibboleth” in defense of his position.

Given all the evidence, we should be long past considering Kennedy a swing vote on abortion. He has voted to allow 20 of the 21 abortion restrictions he has evaluated to take effect. He has sided with the antiabortion position in all of the peripheral abortion cases that have been controversial. And the opinions he has written about abortion have become increasingly hostile to abortion rights.

Looking at Kennedy in this more accurate light, what can we predict about efforts to prevent antiabortion legislation from taking effect? Practically, it probably doesn’t change much in terms of litigation strategy in the Supreme Court. The other four conservative justices are almost guaranteed to vote against abortion rights, so the only option is to try to get Kennedy to take a more moderate position. For advocates before the court, that shouldn’t change, but for those of us who watch on the outside, expectations should be seriously tempered.

With those tempered expectations, all hope isn’t lost though. We have to put our efforts elsewhere and stop hoping for Kennedy to save us. Those efforts can be and have been successful. Political organizing and mobilization can work—just look at Albuquerque earlier this week or California last month. Lower courts, both state and federal, can protect abortion rights, as we’ve seen last month in the Oklahoma Supreme Court and in August in the 9th Circuit. Working to limit the effect of newly passed laws can also be somewhat successful, as Pennsylvania’s recent experience demonstrates. And with the Senate changing the filibuster rules for judicial nominees, we can now focus our efforts on pushing the president to nominate federal judges who are strong and unabashed proponents of abortion rights.

Even in this scary age, there is hope for abortion rights. But we should be honest about one thing: It’s very unlikely to come in the form of Anthony Kennedy.