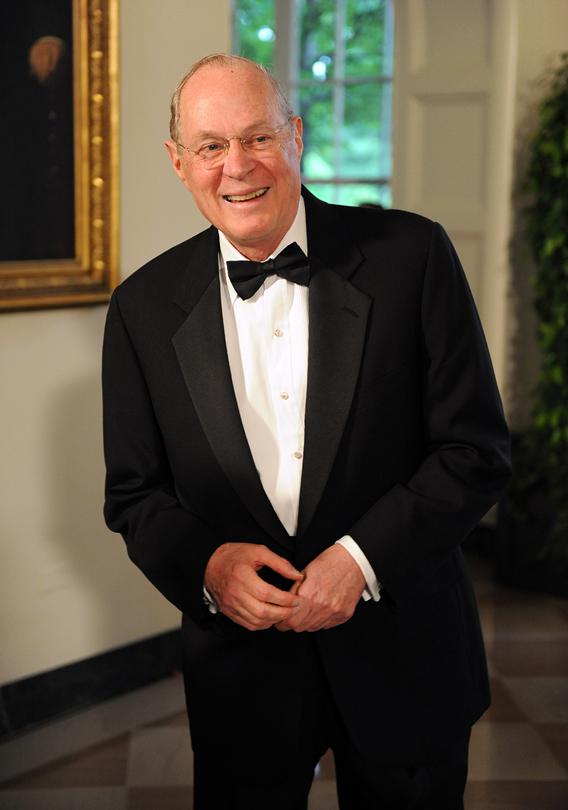

As we creep ever closer to a Supreme Court decision on Obamacare, attention has focused yet again on Justice Anthony Kennedy. It’s a familiar feeling. The prospect that every lower court filing, every judicial decision, every footnote in every brief comes down to a question of how it all plays out in one jurist’s brain. Like the light from a distant star, legal battles that began in far away courtrooms are litigated for years and yet what matters in the end is one judge’s opinion. In a lengthy profile of Kennedy in last week’s Time Magazine, Massimo Calabresi and David Von Drehle write that “on most cases of great moment, the intellectual battlefield of the Supreme Court has shrunk to the space between this one man’s ears.”

Of course, that’s not precisely correct, as those writers stipulate. For one thing, as SCOTUSblog has documented, of the 53 decisions that have already come down this term, 52 percent were decided unanimously and another 11 percent were decided 8-to-1. For another, many, if not most, Supreme Court watchers have suggested that it’s not just Justice Kennedy who will decide the fate of the Affordable Care Act. Chief Justice John Roberts will play as important a role, if not the decisive one. That said, nobody doubts that Kennedy holds the keys to the car in many of the big-ticket decisions this term and next, especially if voting rights and gay marriage come to the court, along with affirmative action. And it does raise questions about the very nature of the judicial project when one man really does hold that kind of influence over the most vital matters of the day.

The Time piece is excellent and well worth reading. But there is one other fascinating characteristic of Justice Kennedy that we often miss: That, of all the current Supreme Court justices, he is in fact most representative of that elusive Every American. Kennedy almost perfectly fits the profile of the mysterious and alluring swing-voter, that vanishing Independent whose vote is truly in play. He is quite conservative, but he exhibits brief moments of progressivism on issues that raise questions of basic justice and dignity—from gay rights to prisoner abuse. Like most Americans, he’s not as conservative as the other four conservatives on the court. Nor, like most Americans, is he as liberal as the four liberals. He tries, as the Time piece highlights, to be open-minded in ways that many of us are not. He doesn’t hate government, although he doesn’t care for it much either. He can be moved by personal narrative. He cares what the rest of the world thinks of this country. And because he is, in a sense, the last of the true swing voters, everyone is always furious at him when he acts in a way that they don’t expect.

Back when Sandra Day O’Connor was the fulcrum of the high court, a good deal of ink was spilled trying to explicate what form of centrism she represented. She was, for one thing, a former legislator and knew how to broker a deal. She was also uncannily able to channel the national public opinion and—fuss as you may about her decisions—there was never a doubt that her decisions often tracked what the national polling showed on issues from abortion to affirmative action to religious freedom. She tacked toward the middle on all things; everyone got a little something and nobody got everything. As Jeffrey Toobin has explained, in comparing Kennedy to O’Connor:

O’Connor was a gradualist, a compromiser, a politician who liked to make each side feel that it won something. When she was in the middle in a case, she would, in effect, give one side fifty-one per cent and the other forty-nine. In Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey, in 1992, she saved abortion rights; in Grutter v. Bollinger, in 2003, she preserved racial preferences in admissions for the University of Michigan law school; in Rasul v. Bush and Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, in 2004, she repudiated the Bush Administration’s approach to the detainees held at Guantánamo Bay. O’Connor split the difference each time. … [Kennedy] tended to swing wildly in one direction or the other. When he was with the liberals, he could be very liberal. His opinion in Lawrence v. Texas, the 2003 opinion striking down laws against consensual sodomy, contains a lyrical celebration of the rights of gay people. In Boumediene v. Bush, the 2008 case about the rights of accused terrorists, he excoriated the Bush Administration and Congress. But in his conservative mode Kennedy could be harshly dismissive of women’s autonomy, as in Gonzales v. Carhart, the 2007 late-term-abortion law case. … Kennedy was not a moderate but an extremist—of varied enthusiasms.

None of that strikes me as inaccurate. O’Connor liked to split the difference and Kennedy likes to drive, even if it means laying out markers on issues he will reserve for a final decision in future cases. O’Connor didn’t represent all of America’s swing voters, who may vote one way and then unexpectedly swing another. Instead, she either consciously or unconsciously channeled broad American preferences. Americans are OK with abortion under certain circumstances, they can live with affirmative action sometimes. So O’Connor gave them all that. She took America’s pulse and wrote it into law and it made people nuts. Kennedy isn’t taking pulses; he turns inward. In a strange way, and on a court that is often accused of being wholly out of touch with ordinary Americans, Justice Kennedy really is the original Independent (to O’Connor’s Everyman). And once again, he may matter most. But oddly enough that means that the Supreme Court looks a lot more like America than most of us believe.