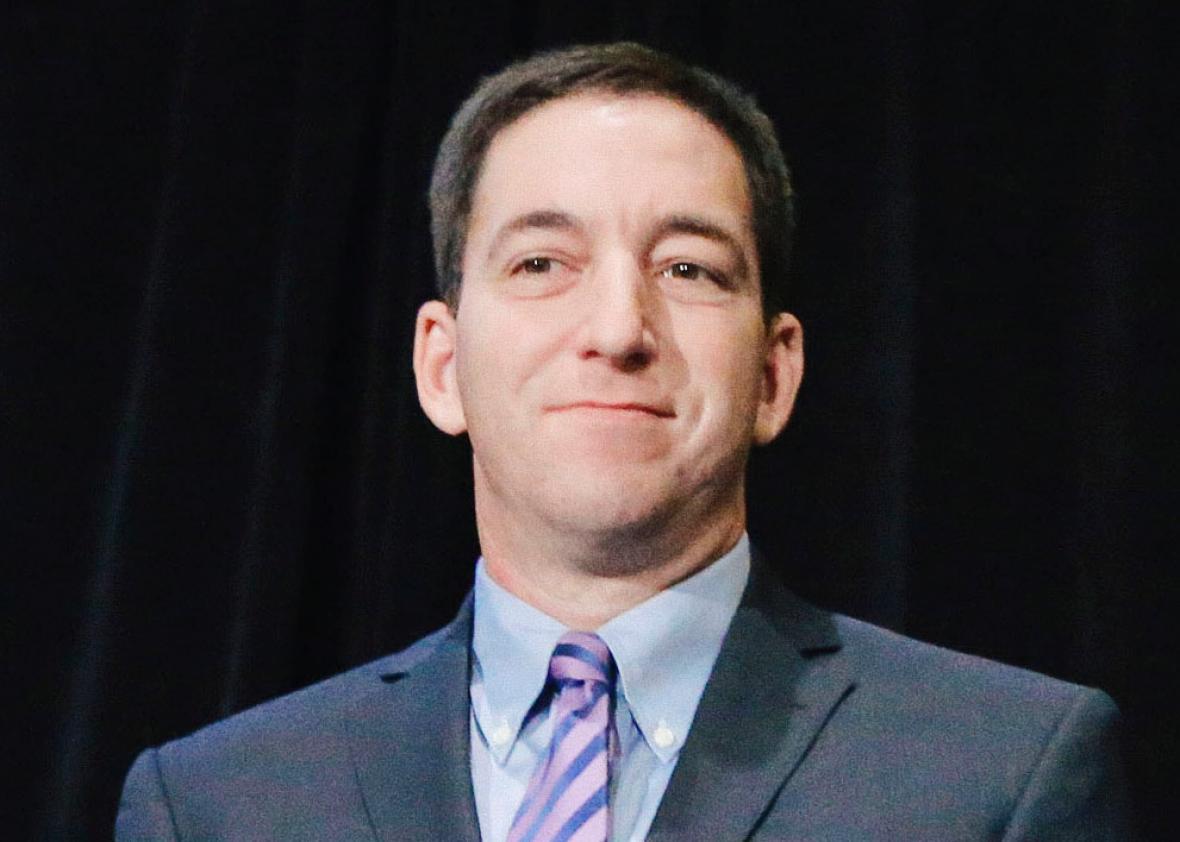

On this week’s episode of my podcast, I Have to Ask, I spoke with Glenn Greenwald, a co-founder of—and writer for—the Intercept. Greenwald is probably best known for his role in reporting on Edward Snowden’s National Security Agency disclosures, which won his reporting team a Pulitzer Prize. He now lives in Brazil and has been writing about the Trump administration and the opposition to it.

Below is a transcript of the show that has been edited and condensed for clarity. In it, we discuss the media’s hypocrisy over covering President Donald Trump and whether we’re really risking a new Cold War with Vladimir Putin’s Russia.

You can find links to every episode here, and the entire interview with Greenwald is also below. Please subscribe to I Have to Ask wherever you get your podcasts.

Isaac Chotiner: A lot of journalists in 2017 have approached the Trump administration in opposition and have said, “This is an unprecedented threat to democracy or to America or to the world,” and this is an incredible time for journalists to be in opposition to power. You seem to me to have approached it a little bit differently.

Glenn Greenwald: I think it’s sort of ironic because when I began writing about politics, I did so very much as a byproduct of dissatisfaction with the media’s refusal to do exactly the things you just said they’re doing now, under the Bush years: that they were refusing to call torture torture, that they were refusing to point out when Bush and Dick Cheney were lying, that they were being insufficiently adversarial.

And the view of journalism I adopted and have been an advocate of now for almost a decade is one that says that journalists should be much more aggressive in their rhetoric and in their journalism; in being adversarial to people who wield political power and calling out lies when they say things that aren’t true; and questioning aggressively the things they say rather than just accepting them on faith; and to not be afraid to have this perception that they’re being too on one side or the other by actually doing journalism.

It’s ironic in one sense that that is what the media has now done with Donald Trump, and I’m glad to see it. My concern, though, is that this change in behavior is very much unique to Trump and that once Trump is gone, it’s going to return to the way things were. My more general concern is that while there are some things that are unique in terms of the threats the Trump presidency poses, there are a lot of things that are just continuations of what has been taking place for a long time that maybe he makes a little bit more manifest. I worry about the whitewashing of history and the rehabilitating of lots of terrible people based on this myth that Trump, and Trump alone, is this malignant force in American politics.

I guess obviously there are other malignant forces in American politics, but do you not feel that we’re dealing with something unique here that should be approached uniquely? Even if the things you say about hypocrisy among people in the media is well-taken and obviously correct at some level.

I think there are some things that are unique. I think the extent to which they are willing to pathologically lie is unique, but I think it’s unique by a matter of degree rather than kind. The journalist who probably has influenced me the most since I’ve been writing about politics is I.F. Stone, and the motto of his journalism was, “Governments lie.” The government lied its way not just into the Iraq war but into the Vietnam War with the Gulf of Tonkin incident.

I think the Trump White House lies more often. I think it lies more readily. I think it lies more blatantly. Is that unique? It’s unique by a matter of degree and not by kind, and I would say that that’s true for a lot of things. One of the things I object to is when I see things that have been done for many years, or even decades, being treated as though they’re things that Trump pioneered. That’s generally when I start being more overtly concerned about the narrative being misleading.

Anyone who’s read about everything from Henry Kissinger to the way the Iraq war was sold cannot say that America doesn’t do things that are horrific, and the things Trump has promised to do—such as bomb people and take their oil, that America has historically done—are things that are indeed that bad. But it does seem that because Trump does present a threat in certain unique ways that at least I feel that people should be welcomed for coming to the right side of something. Even if they should at the same time have to answer for the things that they’ve done or said that were wrong.

I’ll give you an example where I think it’s more than just about hypocrisy, where I think it becomes harmful deceit. When Trump met with Gen. Abdel Fattah el-Sisi of Egypt in the White House, and also when he went to Saudi Arabia and praised the regime, there was all of this sanctimony about how can an American president possibly embrace tyrants this way? When the entire history of post–World War II America is not just embracing tyrants and heaping them with praise, but propping them up with money and with arms.

Hillary Clinton said that Hosni Mubarak, one of the worst despots of the last four decades, was a close friend of her family’s who she looked forward to seeing when he came to the United States. Pretending that Trump is kind of this pioneer of embracing despots, something that the American presidency previously was so anathema to, it’s not just hypocrisy: Democrats didn’t care when Obama hugged Saudi despots, and now they pretend to care when Trump embraces Saudi despots or Egyptian ones. It’s deceitful. It’s creating a false narrative about what the bipartisan class in Washington actually has done, and actually what they still believe in doing, as a way of stigmatizing Trump for something that they themselves all do.

I think as a journalist it’s my obligation to say that this narrative is actually false. I think the times that I get bothered the most is not just simple hypocrisy but when it extends into rewriting history. I got my start writing about primarily civil liberties in the Bush era, and the people who built up my platform and who enabled me to find a readership were Democrats, the liberal blogosphere, and liberals who were saying, “Oh, Glenn Greenwald’s so great. Look at this critique he’s making of the Bush administration, their executive power theories, their law-breaking.”

And then when Bush left office and Obama came in and continued many of those same policies, a lot of those people not only stopped caring, they started defending those policies and attacking those of us who were consistent. I don’t actually think that there’s limited value even in people who pretend to care about issues only for partisan opportunism and gain. I actually think those people are really harmful because the minute those policies are embraced by members of their own party, they’re going to become cheerleaders for them, and I’m not interested in vesting them with credibility in order to do that.

That’s a fair critique, but I also think that you can say that everyone is hypocritical to some degree, obviously different levels, and that when people do take the right position on something, they should be applauded for that …

My psychological reading of what’s going on is you brought up the post–Cold War world and you said, “Look, America has supported one despot after another in many cases. They’ve done all these horrible things,” and you also have Ronald Reagan or Jeane Kirkpatrick, I think, what was it? That Jonas Savimbi was a philosopher or something like that. I can’t remember the exact quote.

Yeah, yeah.

But quotes that are basically as ridiculous as you could find Trump saying about Sisi. I agree that that’s all true, and much of it is completely shameful. I think the difference among people is that there was a sense that a lot of this stuff was realpolitik. It was done to uphold the Western world order, and that world order was being upheld because fundamentally it offered certain freedoms, et cetera, that in the long run were good.

Are you talking about the Cold War? You’re talking about the Cold War mentality?

Yes, and then the post–Cold War, I think what scares people about Trump is there’s a sense that not only is he speaking up for dictators, but he has no respect for the good aspects of this world order—whether it’s peace in Europe, peace in Western Europe, or a commitment to certain civil rights and civil liberties that our country’s obviously practiced very insufficiently at times, but also in some ways has a commitment to. I think the fact that people think that he has no commitment to any of these principles is what scares people and why you see this reaction. I don’t think that’s totally insane.

So, here’s what I will agree has validity, which is that Trump often seems to heap praise on dictators—just as Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton and Bill Clinton and whoever your favorite Democrat did—not because they’re strategic partners of the U.S. and advanced U.S. interests, which by the way, doing it for that reason is a horrible, evil thing, but he goes beyond that and expresses almost an envy that he wishes and aspires to their level of totalitarian power. The more totalitarian power they exercise, the more fearful their domestic opponents are, the more he respects them because that’s what he sees himself as aspiring to as a leader. That I do think is alarming and scary and different. I agree with that part of it.

I have a lot of trouble with this idea that when politicians do something really destructive and immoral, we’re supposed to look into their hearts and feel, “Well, they’re just doing it begrudgingly. They wish they didn’t have to do that, but they’re doing it because they think they should,” as opposed to because they really like it or because in the ideal world they would be doing it. There’s just no way to know that. Hillary Clinton sounded really genuine when she talked about Hosni Mubarak. I think the reason is because they deal so much with these dictators, and these dictators do become their partners, they start excusing and mitigating all of their crimes. I think both the Cold War order and the post–Cold War order has been very much a story of the U.S. not just tolerating dictators, but seeking them out and trying to strengthen them on the grounds that doing so will advance U.S. interests.

One of the things I found most disturbing about the 2016 election was when Trump raised questions about NATO, and whether NATO was obsolete, in light of the fact that there’s no more communism and no more Soviet Union that it was originally created to fight. Whether the vast expenditures that we lay out for NATO military and NATO forces is something that we ought to continue to do, whether the military adventures of NATO in Libya and elsewhere have actually been something that has served the national interest.

To me, these are totally legitimate questions. I don’t think NATO has kept the peace. If you live in Paris and you live in London, then it has, but if you live in Somalia, or you live in Yemen, or you live in Libya, or you live in Iraq, then it hasn’t. I think we ought to be able to have a good-faith debate about things—are these international institutions that continue to exert military force in the name of the Western alliance doing more harm than good? Is it really worth the outlay?—without being accused of being treasonous, or Vladimir Putin’s puppet, or anything like that. I think that’s a debate that’s valid and worth having.

I haven’t given a lot of thought to NATO, collective security, and the future of the alliance, but to me it almost seems more important now than it did three years ago, not because Trump is speaking out—I won’t say “against it” exactly, but speaking out while mincing words about it. But also because we now have a president who speaks approvingly of Vladimir Putin trying to hack Western elections.

When you say that kind of stuff, it sounds to me like you almost are describing a new Cold War. The original justification of NATO was that it needed to band together in order to defend the West against this pernicious ideology emanating from Moscow. What I hear you saying, and lots of other people saying, is that the reason we still need NATO, notwithstanding the collapse of communism, is because there’s this pernicious ideological movement emanating from Moscow that we need to unite in defense against.

One of the reasons why I find that so alarming, aside from all the obvious destruction the Cold War wreaked the first time around, is because if you look at what President Obama was saying for eight years—it’s one of the things that I agreed with him so much on and often expressed praise for him for doing—he was extremely reluctant to adopt this worldview that held that Russia was this new, serious geopolitical threat. He constantly mocked the idea, most famously in the 2012 debate with Mitt Romney, but in other instances as well.

He often pointed out that Russia’s economy is smaller than Italy’s. He refused to arm anti-Russian factions in Ukraine; he didn’t want to confront the Russians in Syria notwithstanding a bipartisan demand that he do so. The reason for that was he understood that if we escalate tensions with Russia by exaggerating the threat that it poses to our country, then we could find ourselves in the midst of a new Cold War, which was so destructive the first time around. I think he was right for eight years, and I still think he’s right, notwithstanding the fact that—let’s assume it’s true—some Russians successfully sent phishing links to John Podesta and then leaked his emails. I don’t think that changes the geopolitical reality in such a fundamental way as I think your question suggests.

It does seem like things have changed in the last couple years. It’s continuing Russian action in Eastern Ukraine post–annexation of Crimea. It’s phishing links to John Podesta, but it does seem like, according to some of our intelligence agencies and reporting, there is at least a larger effort on the part of the Russians to interfere in several Western elections, which I assume will be ongoing. This all seems like it changes the picture at least somewhat. Do you not feel like what we’ve learned, or what we’ve seemed to have learned, in the last year about Russian interference and Russian behavior vis-à-vis the election has changed at all the way you think about it?

First of all, and I know this is blasphemous to say, I still think it is worth underscoring that the United States government has to this very moment still not presented actual evidence, as opposed to claims and assertions, that Vladimir Putin ordered the hacking of the Democratic National Committee and John Podesta’s emails in order to sway the election in favor of Donald Trump. I know we’re all duty-bound to accept that this is true—I know that if we question it, it means that we’re being irrational—but I do just want to point out that the evidence for this, presented by the U.S. government, is essentially nonexistent.

Remember, there were a lot of claims made during the French election about the hacking of Emmanuel Macron’s emails that were said to be done by the Russians, that forensic investigations once the election was over concluded probably weren’t true, that it wasn’t really the Russians who did at least those kind of hacks. Now, I don’t doubt at all that the Kremlin interferes in Western domestic politics by trying to sew divisions, by trying to support factions that it believes are better for its interests as opposed to worse for its interests. I don’t even doubt that the Kremlin wanted Trump to win over Clinton, given that she was saying she essentially wanted regime change in Syria and we should confront the Russians more aggressively in Ukraine, and Trump was taking the opposite view.

All I’m saying is that even if all of that is true, they’re interfering in this way, this is banal. This is garden-variety interference. This is the stuff that the U.S. does constantly all the time. Now, I’m not saying that that justifies what the Russians are doing, but I think we have to put these threats in perspective. There is a huge difference between having a country be a military threat to the United States—that they’re going to send terrorists or fighters into our borders to harm our citizens, or blow things up, or that there’s missiles pointed at our cities … that’s the kind of real threat to our security that I think we need to sound the alarms in order to defend against. But hacking emails and supporting parties? This is stuff we do to them, and have done to them for decades, and still continue to do. I think it’s very easy to focus only on those isolated threats, but I think it’s so important to try to keep in perspective how grave of an aberration that that really is from the international order and how nation-states deal with one another.

BuzzFeed has had a lot of reports on what seemed to possibly be assassinations in the U.K. There have been cases here—

Of Russians, of Russians.

Right, but assassinating—this is the type of thing Chile’s Augusto Pinochet did I think in the United States. I don’t know anyone else or any other foreign government who’s done that in the United States, but assassinating people on foreign territory is generally considered not a good thing, an extreme act …

And again, the Trump stuff, just to try to understand psychologically why you called it a “new Cold War,” why people are so scared about this—it just does seem Trump’s behavior around Putin and Russia is so bizarre. It’s one of the very few things he’s been legalistically consistent about, time and time again. It’s weird, and I think people don’t understand it, and they’re worried about it, and I think it fits into this larger thing about the one difference between Trump’s praise of dictators is that he in some ways seems to envy them. I think that that creeps people out, that he legitimately seems to almost envy the type of power Putin has and his connections or rumored connections, which are now being investigated with the Russians. I think it makes sense why people are feeling like this is a threat and this is something to be nervous about.

I think it’s important not to conflate those things. There are other world leaders that Trump has uniformly praised. He has uniformly praised the leaders of the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia. He has uniformly praised Benjamin Netanyahu. He has never uttered a syllable of criticism about Netanyahu. People love to say, “Putin’s the only one that he hasn’t criticized who’s a world leader.” It’s just not true. He loves Israel, he loves the Saudis, he loves the Emirates, he loves the Gulf states. Also, Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines who he’s never uttered a single bad word about.

But there’s no countervailing pressure on any of those things, unfortunately.

I think we’re in agreement that Trump has serious authoritarian tendencies that I think are dangerous and need to be guarded against. I actually think that one of the really positive things about the Trump presidency has been the way it has revitalized a lot of dormant checks. You were just saying how vibrant and aggressive and pugnacious the U.S. media has been since Trump’s election, which I agree with. That’s great to see, that the idea of adversarial journalism lives and breathes again outside of fringes.

I think the way that courts have stood up to Trump and said that a lot of his policies are in violation of the Constitution and struck them down—something I wish they had done during the war on terror, under the Bush and the Obama administrations—is incredibly good to see as well. Then most of all, I think that citizen activism has really been revitalized. I agree with you that Trump has authoritarian tendencies, that he would love to exert a form of despotic power, at least when his wall is thwarted. I think it’s very much worth watching, and I think it is actually scary as well, but I also think that the institutions that are designed to check those tendencies have been stimulated in a really encouraging way by the fear that people have of him.

One of the institutions that I think a lot of people think has checked Trump in some way is what’s half-ironically or sometimes not ironically called the “deep state,” which is people who are leaking information from the government, or assumed people leaking from the government, about various goings-on with Trump. You’ve written a lot about this, and it seems like one of the fears that you have is that the deep state, or figures in the national security establishment who are opposed to the democratically elected president to the United States, would in the long run undermine democracy in some way. What specifically are you scared of about this unprecedented opposition we’re seeing from within the government to Trump?

This theory that there’s this kind of unelected permanent power faction in Washington composed of, at least in part, the intelligence and military community gets treated so often like it’s some deep, dark, exotic, bizarre fringe conspiracy theory, when in reality it’s totally basic to how very sophisticated people have talked about Washington for decades. The person who originated the theory was Dwight Eisenhower, in his farewell speech, after serving for eight years as president. The one thing he wanted to warn Americans about was that these unelected factions were threatening democratic accountability because they were becoming more powerful than even elected officials like him, because he had butted heads so often.

He was a five-star general, and he was worried about them 50 years ago before they boomed in power and size with the Vietnam War, followed by Reagan and the Cold War, followed by the war on terror. This idea that there’s a really powerful, dangerous element in Washington that operates in the dark with very little transparency and accountability, or democratic checks, is something you can mock all you want. It’s very elemental to understanding how Washington works once you get passed a sixth-grade civics class.

I guess the thing that I do really worry about: It’s sort of like in Syria. What’s so tragic about Syria is that the choice that people ended up being given was picking between Bashar al-Assad or al-Qaida or ISIS once the ordinary people of the Syrian revolution got defeated. You just had to choose between awful choices, and I’m really worried about having this choice in the U.S.—between Trump and whatever you want to call it. Call it the deep state, call it the national security blob, call it the CIA and the Pentagon, because I think that as dangerous as Trump is, those factions have proven extremely dangerous as well, particularly when they start interfering in domestic politics even if you’re happy about the results that they’re, at the moment, bringing about.

But when people are leaking stuff to the media about what they think is going on that’s newsworthy I assume, generally speaking, that’s a trend that you’re happy about?

I’m totally in favor of leaks, but at the same time, let’s think of some hypotheticals, and then I’d love to know whether as a journalist it would bother you.

I’m not a journalist, Glenn. Come on. Come on.

Yeah, just a podcast host. But you’re a striving journalist. Let’s say that like the NSA, some people inside the NSA start getting emails of people they dislike because those people are advocating policies that they regard as wrong, and they start leaking their emails and their telephone calls to the Washington Post and the New York Times, and then attempt to harm their reputation and discredit them. In one sense, as a journalist or somebody who favors transparency, you can say, “Well, that’s a good thing. They really did say those things. It’s newsworthy, and I’m happy that this has become public.”

But on the other hand, it’s also an abuse of power for the NSA or the CIA to take the intelligence that they’re gathering about people and then use it to harm domestic enemies. I think that there are two sides to that coin, and both are serious ones.

But if you look at something like the DNC hacks, that was illegally taken information that the media reported on. I assume you think they should have reported on it.

That’s a great example of what I was just saying, which is on the one hand I do think there was newsworthy information within both the Podesta emails and the DNC leaks that ought to have been public. On the other hand, I think there were disturbing aspects of how that leak was handled. There was some really personal information about people that had very little public interest, that should never have seen the light of day, and that harmed people’s privacy and reputations.

I think you can be a fan of that leak in one way, in terms of the transparency it brings, as I was with the DNC and Podesta leaks, as I am for a lot of the leaks that have taken place—even the illegal ones like proving that Michael Flynn lied about his meetings with Russian Ambassador Sergey Kislyak. But on the other hand, I can recognize the harms and dangers that both of those pose.