The cover of this week’s National Enquirer features a wan, gray Hillary Clinton, looking like she has been drained of all her vital fluids. The photograph, if you can call it that, is a perfect visual artifact of the recent storm of right-wing rumormongering over Clinton’s health, which spilled into the mainstream media this past weekend when Clinton revealed a pneumonia diagnosis that would keep her off the campaign trail for a few days while she underwent treatment.

As more than one observer has pointed out this week, there is sexism at the root of this constant scrutiny of Clinton’s “stamina.” Her opponents amplify any small sign of corporeal weakness in the female candidate, while her overweight, KFC-eating, very lightly exercising opponent of roughly the same age gets a pass. But where does this sexism come from? The long record of American beliefs about women’s bodies and health sheds some light on this week’s overreaction to Clinton’s illness. In the United States, powerful women who make bids for education, status, and position have long been seen as sick: weak, sterile, overweight, ugly, or broken. These ideas may seem antediluvian; this week proves they are still very much alive.

“Many of these conversations about women, work, and education can be traced back to good old Dr. Edward H. Clarke,” historian Jacqueline Antonovich, editor of Nursing Clio, a group blog about gender, medicine, and history, wrote to me. Clarke, a physician who taught at Harvard, published an influential book in 1873: Sex in Education; Or, a Fair Chance for the Girls. He argued that educating women at the college level was “a crime before God and humanity, that physiology protests against, and that experience weeps over.” As historian Sue Zschoche writes, Clarke thought “the female college graduate would be renowned for invalidism rather than erudition, sterility rather than achievement, a degenerate femininity rather than true womanliness.” Because the female body was unable to direct energy toward both reproduction and thought, the educated white female would inevitably betray her own gender—and her race—by failing to have children. (He didn’t think she would be much good at her job, either.)

The “race” part was important to Clarke, who, thinking eugenically like many of his late-19th-century peers, feared the specter of falling birth rates among upper-class, native-born white women. But race is also a key part of the history of women’s health in the 19th century, in which the “normal” female body was always white. As historian Ava Purkiss wrote to me, “Middle-class and wealthy white women, whether they were politically powerful or not, have been seen as frail.” Black women, on the other hand, were often seen as “strong and able to bear many burdens … many believed that black women were immune from over-exhaustion and sickness.” (This perception has, of course, had its own set of negative effects.)

Clarke’s book had a huge influence on white middle-class women’s lives, Antonovich pointed out, precisely because Clarke “wrote it at a time when more women were seeking higher education and entering the legal and medical professions.” By telling themselves they were saving such women from grievous physical harm by shutting them out of higher education, gatekeepers could consider themselves paternalistic benefactors. Historian Lauren MacIvor Thompson wrote to me that in the early 20th century, “Perceptions of women’s constant ill health were not only propagated by physicians like Clarke, but also literally built into the law.” For example, in the 1908 Supreme Court decision Muller v. Oregon, future Justice Louis Brandeis (then in private practice) successfully argued that women’s working hours should be restricted, because their biology meant they needed special protection from the state.

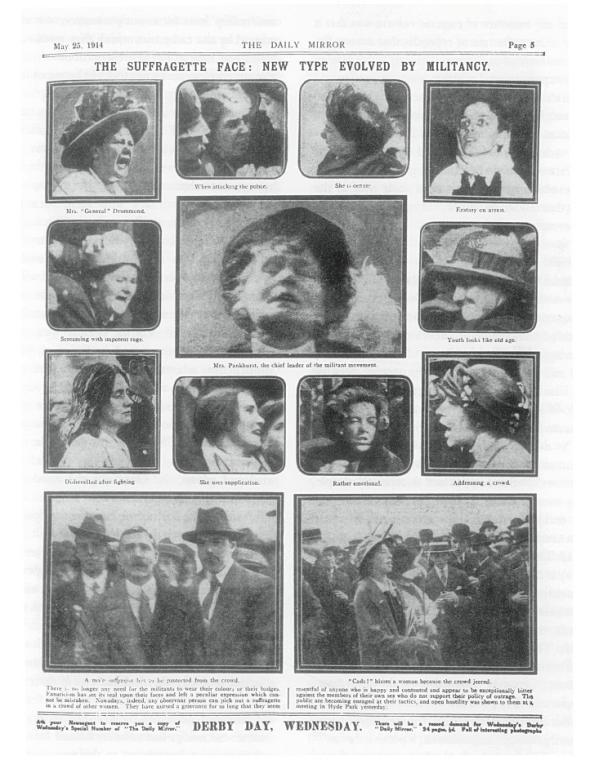

Women who dared defy the paternalistic limits on their ambitions were often accused of bad health. In early 20th-century American and English debates over women’s suffrage, anti-suffrage propaganda depicted suffragists as overweight, ugly, and “mannish”—their bodies and faces physically reflecting their own unnatural sentiments. “Throughout the long struggle for women’s suffrage, anti-women’s rights activists argued that the suffrage movement both attracted and created women who were primitive and out of control,” writes historian Amy Erdman Farrell in her book Fat Shame: Stigma and the Fat Body in American Culture. Farrell points to a 1914 pictorial spread in the London Daily Mirror: “The Suffragette Face: New Type Evolved by Militancy,” a grid of portraits that was supposed to illustrate the severe distortion of womanly features by the unnatural emotions of political activism. Like the Enquirer’s portrait of Hillary, anti-suffrage propaganda like the Mirror spread was supposed to be incontrovertible proof of feminine decay.

But an episode from very early in American history offers perhaps the most vivid illustration of the long American belief that powerful women must pay for it in their bodies. Historian Ann M. Little, author most recently of The Many Captivities of Esther Wheelwright, pointed me to the case of Anne Hutchinson. Hutchinson started a popular lay religious discussion group while living in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in the 1630s and soon found herself at odds with the clergymen who ran the settlement. She bore 15 children before, at age 46, in exile in Rhode Island, she miscarried a series of formless masses of flesh.

We now suppose she may have had a molar pregnancy, but at the time, religious men threatened by Hutchinson’s ideas argued that the “monstrous birth” was a fair judgment for her transgressions. John Winthrop wrote of it and a similar miscarriage suffered by one of Hutchinson’s female supporters:

Then God was pleased to step in with his casting voice, and bring his owne vote and suffrage from heaven, by testifying his displeasure against their opinions and practices, as clearely as if he had pointed with his finger, in causing the two fomenting women in the time of the height of the Opinions to produce out of their wombs, as before they had out of their braines, such monstrous births as no Chronicle (I thinke) hardly ever recorded the like.

This old, sad story helps get at the crux of the fixation on Clinton’s body and brain; both Clinton and Hutchison, Little suggested, are seen as “ambitious women felled by [their] own anatomy.” The idea that female success is a crime against the natural order has had a startlingly long shelf life in American culture. A story in the National Enquirer, last year, began: “Failing health and a deadly thirst for power are driving Hillary Clinton to an early grave.” Hillary is an older white woman who has defied cultural expectations, accumulating positions of influence and racking up successes in the public eye. She has desired a position she doesn’t deserve and she isn’t suited for; she must be paying with her flesh.