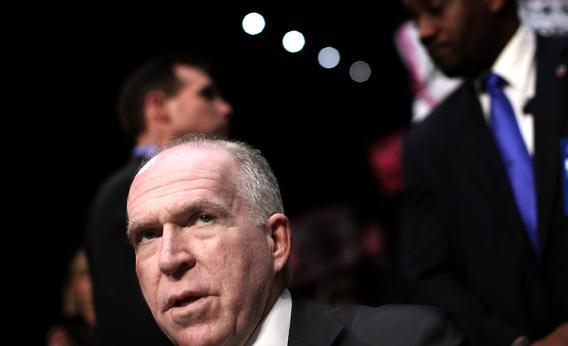

Many expected John Brennan’s confirmation hearing would unleash a great debate on the wisdom, legality, and morality of U.S. drone strikes. In that sense, many should have come away from the hearings disappointed.

The panelists of the Senate Intelligence Committee asked Brennan plenty of questions about whether he’d give them documents about drone strikes and other practices if he’s confirmed as CIA director—but they asked very few about the practices themselves.

Even in the face of this striking incuriosity, Brennan supplied a few intriguing nuggets. For instance, he acknowledged once saying that “enhanced interrogation” had yielded useful information in finding and capturing terrorists, including Osama bin Laden—but, he added that, after reading the first volume of the Senate committee’s still-classified 6,000-page review of the subject, he now has doubts. He said he would await the CIA’s review of the report for final judgment, but for the moment he finds the report “very concerning and disturbing.”

The fact that Brennan has been President Obama’s senior adviser on counterterrorism these past four years, and yet found material in the Senate report that he had not known before, material that makes him now think he might have been wrong—this in itself is rather disturbing.

Brennan made several other interesting remarks—for instance, that waterboarding should have always been banned, that the CIA should not interrogate terrorists, and that the CIA “should not be doing traditional military actions and operations”—but the senators rarely followed up. For instance, they didn’t ask whether “traditional” operations included drone strikes—or much else about drone strikes, despite the issue’s prominence in recent debates. The Intelligence Committee itself has been demanding a copy of the Justice Department’s full legal justification for drone strikes—or, more specifically, for targeted assassination against al-Qaida operatives, even if they’re American citizens. An unclassified, 16-page summary of this document was leaked to the press earlier this week, and has been much-discussed since—yet the senators asked nothing about it.

This is too bad, for this “white paper”—as the summary is titled—is, in its own way, concerning and disturbing.

The white paper stresses that three conditions must be met before the United States launches a strike against an individual in a foreign country where we are not formally at war.

First, it states, “an informed, high-level” U.S. official must have “determined that the targeted individual poses an imminent threat of violent attack against the United States.” Second, it must be concluded that capturing this targeted individual “is infeasible.” Third, “the operation would be conducted in a manner consistent with applicable law-of-war principles,” that is, with particular attention to minimizing civilian casualties and assuring that the gains of the operation are proportionate to its risks.

Let’s ignore for a moment the ambiguity of “an informed, high-level official” (how informed, how high-level—the president, the CIA director, a commander in the field?). Instead, let us focus on the phrase “imminent threat of violent attack against the United States,” with special emphasis on “imminent.”

The word imminent has a straightforward meaning, but not in this document, which states, with no apology or irony:

The condition that an operational leader [of al Qaida or an affiliated organization] presents an “imminent” threat of violent attack against the United States does not require the United States to have clear evidence that a specific attack…will take place in the immediate future.

In other words, imminent does not mean imminent.

The logic behind this illogic is no less startling. Al-Qaida leaders, the white paper asserts, are “continually planning attacks” against the United States. “By its nature, therefore,” the threat posed by these groups “demands a broad concept of imminence.” Or, to put it another way, the threat of an attack is always imminent, even if there isn’t the slightest evidence of an actual attack on the horizon, imminent (in the conversational sense of the word) or otherwise.

And so, the first condition that must be met before a U.S. official can assassinate a suspected terrorist—the presence of an “imminent” threat of attack—is, by this circular logic, a constant condition; there is no need to meet the condition; it is not remotely a restriction.

The second condition—the infeasibility of capturing the terrorist—is similarly lax. Because the threat is always “imminent,” as defined by the white paper, “the United States is likely to have only a limited window of opportunity” for mobilizing a raid to nab the terrorist on the ground. In other words, merely capturing the terrorist is always “infeasible.” This condition, too, is not at all a restriction.

The third condition—concerning law of war principles—is a real restriction. Advanced technology has allowed the CIA to use small, very accurate weapons in these air strikes; it doesn’t drop massive bombs. And so, while civilians are sometimes killed, the “collateral damage” has been relatively minor. There are also cases where officials have decided not to push the button if the target of an attack was surrounded by too many innocent people.

It may be true that, even when it comes to the first two conditions, the “informed, high-level officials” in the Obama administration—including Brennan, who has been deeply involved in these decisions—have exercised good judgment. But we don’t know this; we have no way of knowing this. And by “we,” I mean not just those of who of us who don’t have the proper security clearances, but also those who do (outside, of course, the very small group that makes the decisions of life or death).

And that’s the point. The white paper acknowledges that there is no entity—in the executive, legislative, or judicial branch—that has the authority to oversee these sorts of decisions. But maybe there should be. Sen. Dianne Feinstein, the California Democrat who co-chairs the Intelligence Committee, suggested at Thursday’s hearing that an analog to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court might be created to sign off on these orders, especially if American citizens are the targets. Not a bad idea.

But the logic of the three conditions—or at least the two conditions that aren’t at all restrictive—raises questions not just of legality but of policy. Gen. David Petraeus once said of the Iraq war, “Tell me how this ends.” The same question can be asked of this war. Are there no limits to targeted assassination? Are we going to be doing this as long as terrorist organizations exist? What is the effect? Does it really reduce terrorism and pummel the organization—or are the killed leaders simply replaced by underlings waiting in the wings?

The question, unasked by the senators today, isn’t simply whether this is legal but whether this is wise.