In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the United States suffered through a skyjacking epidemic that has now been largely forgotten. In his new book, The Skies Belong to Us: Love and Terror in the Golden Age of Hijacking, Brendan I. Koerner tells the story of the chaotic age when jets were routinely commandeered by the desperate and disillusioned. In the run-up to his book’s publication on June 18, Koerner has been writing a daily series of skyjacker profiles. Slate is running the final dozen of these “Skyjacker of the Day” entries.

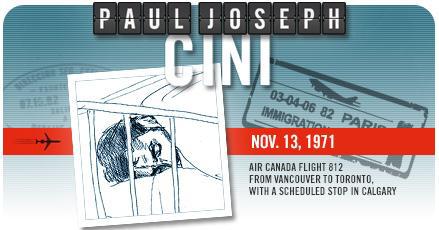

Name: Paul Joseph Cini

Date: Nov. 13, 1971

Flight Info: Air Canada Flight 812 from Vancouver to Toronto, with a scheduled stop in Calgary

The Story: At a congressional hearing in 1969, a Federal Aviation Administration psychologist named John Dailey testified that skyjackers were primarily motivated by a need for public recognition. “He is like the Indian scalp hunter,” said Dailey. “If the other Indians didn’t know when he scalped someone, he wouldn’t do it.” That statement may have been a gross overgeneralization, but it certainly applied to Paul Joseph Cini, a man who botched his quest for fame by tying a knot too tightly.

In September 1970, while downing shots of vodka in his Victoria, British Columbia, apartment, Cini had watched a television news segment about a failed hijacking for ransom. In the midst of the story, his alcohol-fuzzed mind somehow managed to produce a eureka moment: The best way for a hijacker to escape justice was not to fly abroad, but rather to jump from the plane.

Cini initially had no designs on attempting this himself, as he was deathly afraid of heights—during his brief stint in the Canadian army, in fact, he had been too petrified to scale a telephone pole during a training exercise. But the more he contemplated the risky caper, the more he became convinced that it represented his one shot at improving his lackluster life, which was marred by alcoholism and dim job prospects. “I wanted recognition,” he would later explain. “I wanted to stand up and say, ‘Hey, I’m Paul Cini, and I’m here and I exist and I want to be noticed.’ ”

Cini boarded Flight 812 in Calgary with a bag containing everything he thought he would need to pull off the hijacking and then survive in the wilderness after jumping from the plane: a sawed-off shotgun, dynamite, a sheepskin rope, a collapsible shovel, a pup tent, candy bars, hiking boots, and a dark-blue parachute wrapped in a paper bag. After downing several Screwdrivers, he brandished the weapons and announced that he was a member of the Irish Republican Army who would blow up the DC-8 unless he was given $1.5 million and passage to Ireland. The plane landed in Great Falls, Mont., where Cini received all the cash that Air Canada could muster on short notice—a mere $50,000. Unlike fellow hijacker Arthur Gates Barkley, who had freaked out when TWA shorted him by $99,899,250, Cini didn’t mind the lesser ransom.

The DC-8 was en route back to Calgary to refuel when Cini told the crew to open one of the emergency exits so he could jump to freedom. But try as he might, Cini couldn’t undo the twine that he had used to wrap his parachute—the knot was too tight, especially for a man whose fine motor skills were impaired by copious amounts of liquor.

The frustrated Cini asked one of the pilots to lend him a sharp instrument to cut free his parachute. When the pilot offered him the DC-8’s fire ax, Cini absentmindedly laid down his shotgun to accept it. Seeing that the hijacker was now unarmed, the pilot kicked away the shotgun and grabbed Cini by the throat. Another crew member took the ax and smashed it into Cini’s head, fracturing his skull. Paul Joseph Cini would be remembered not as the world’s first “parajacker” but as a fool.

The Upshot: The fame that Cini so desperately craved would instead go the fabled D.B. Cooper, who jumped out of a Northwest Orient Airlines jet 11 days later and was never seen again. Cini was sentenced to life in prison in April 1972, though he was paroled after serving just 10 years.